- Health

What has been the effect of the pandemic on the suicide rate of the U.S. population?

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted countries everywhere to take measures to reduce the spread of the disease. One of these measures, which has proven to be effective (as covered in several Health Feedback claim reviews here, here, and here) but hasn’t been without controversy, is lockdown. Lockdowns consist of limiting certain activities by the general population and private businesses, such as attending school and gatherings[1].

One reason for the controversy, with this and other measures like travel bans, is due to whether or not their potential benefits outweighed their potential economic and psychological costs. In May 2021, a roundtable held by U.S. Senator Rand Paul in Lexington, Kentucky, discussed the impacts of lockdowns on small businesses.

In a video clip that went viral on social media, Paul, who chaired the roundtable, discussed among other things the negative impact the school closures had on children, implying that this led to an increase in children’s suicide rate. Specifically, he stated that more children have died by suicide than by COVID-19. Another participant in the roundtable, Dawne Perkins, claimed that this was due to the economic hardship that some families are facing during the pandemic, leading to poorer living conditions in these children’s homes.

In this article we provide perspective on this subject by discussing suicide rates in the U.S. prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the potential effects that the pandemic had on suicides in general and on children specifically.

The short-term impact of the pandemic was a decrease in the overall suicide rate

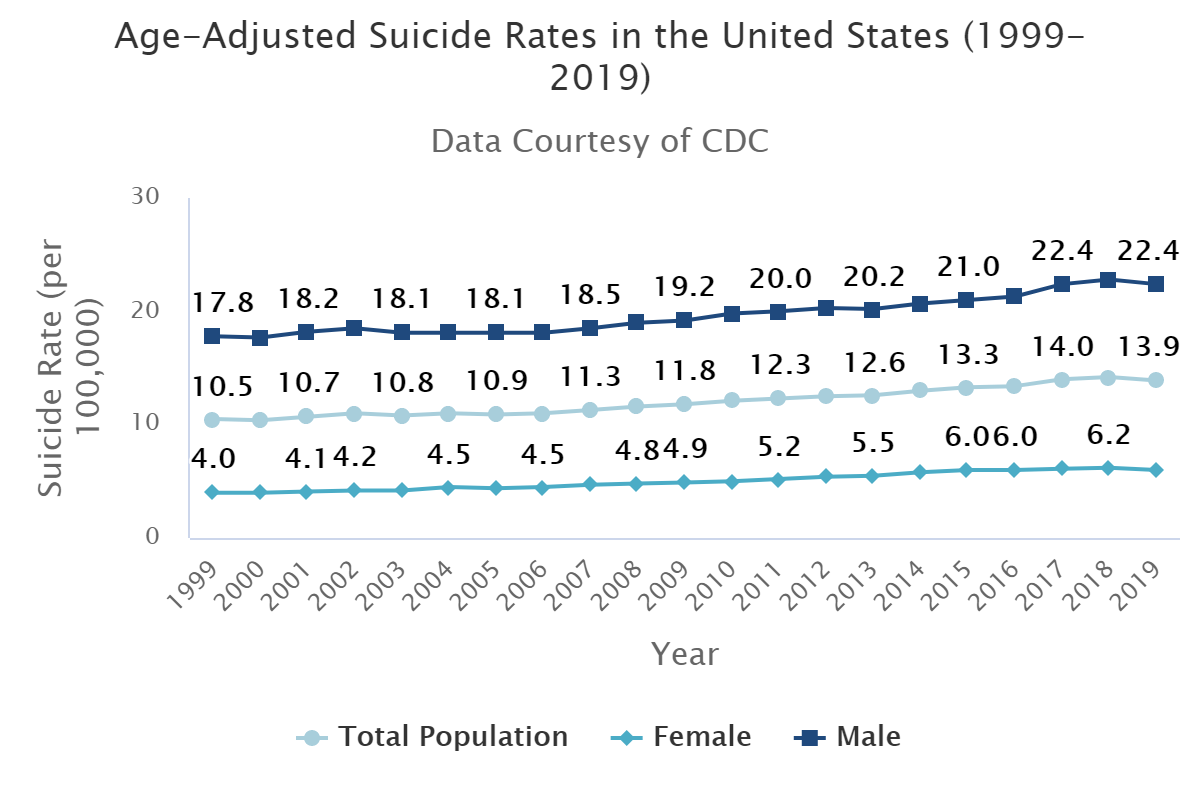

The U.S. has been experiencing an increasing suicide rate with every year since 2007. Therefore, this increase began long before the pandemic, with a 35% increase between 1999 and 2018, and a slight decline in 2019, according to the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)(Figure 1). According to the NIMH, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the U.S., claiming the lives of 47,500 people in 2019.

Figure 1. Suicide rates by gender in the U.S. between 1999 and 2019. Source: U.S. National Institute of Mental Health.

During the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was concern about a possible increase in suicides[2]. This could happen for various reasons, such as economic difficulties associated with job loss, anxiety associated with the possibility of contracting COVID-19, social isolation, difficulty in getting medical care, and domestic abuse.

However, contrary to expectations, the available data so far don’t show an increase in the overall suicide rate in 2020. A study published in April 2021 using data from 21 countries found that suicide rates didn’t increase at the onset of the pandemic, and in several of these countries (Australia, Canada, Chile, Ecuador, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and the U.S.), the expected suicide rate actually decreased[3].

A report by scientists at the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics found that the suicide rate in the U.S. decreased by 5.6% in 2020, based on provisional data. Likewise, another study carried out in Massachusetts found no increase in the suicide rate during the COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Advisory, from March to May 2020[4]. However, these sets of data should be taken with caution, as the authors of the cited studies warned. The data cover only the early half of the pandemic, and we don’t have the full picture yet. The pandemic is still ongoing and it is still too early to know its long-term effects on the mental health of the population.

Researchers proposed that a decline in the suicide rate during the early days of the pandemic could be due to the sense of community that is created after a natural disaster. This is also known as the “pulling together” phenomenon, which has been documented after natural disasters. This phenomenon results in a decreased suicide rate despite the increased level of stress among the population.

However, one important aspect to account for when interpreting suicide rates is that the rate can vary greatly based on demographic or ethnic factors. In the U.S., despite the decrease in overall suicide rate during 2020, some states such as Illinois, Maryland, and Connecticut saw an increased suicide rate among the non-white population, as the New York Times reported. For example, in Illinois, the overall suicide rate decreased by 6.8%, but increased by 27.7% among Black residents.

A live systematic review still under development found no evidence of an increase in suicidal behaviour or self-harm in the U.S. due to COVID-19 or measures taken to curb its spread. It did, on the other hand, find an increase in suicidal ideation in people who had been infected with COVID-19. This finding is in line with previous studies, which found that COVID-19 survivors had an increased risk of neurological disorders and psychiatric sequelae[5,6]. This highlights that the disease, and not only the measures taken to curb its spread, can have a negative impact on the mental health of the population.

There is insufficient data to determine the impact of school closures on child suicides

The World Health Organization (WHO) explains that “Adolescence is a crucial period for developing and maintaining social and emotional habits important for mental well-being.” It also highlights several factors that could contribute to the development of mental health problems, such as living conditions, access to mental health-related resources and support, and various socioeconomic factors.

In the U.S., suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 10 to 24, second only to unintentional injury. The suicide rate in this group increased dramatically between 2007 and 2018 by nearly 60%, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

According to the CDC, 195 people aged 0 to 17 and 1,417 people aged 18 to 29 died in the U.S. during 2020 as a result of COVID-19. Data regarding deaths by suicide during 2020 aren’t available yet, but according to the NIMH, suicides claimed the lives of 534 people aged 10 to 14 and 5,954 people aged 15 to 24 in 2019. If these numbers for 2019 also reflect those for 2020, then suicides among children and young people would indeed be higher than deaths from COVID-19, as Paul claimed.

Furthermore, preliminary data suggest that the trend in suicides among children and young adults increased in 2020. A study carried out in Texas found an increase in the rate of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts for people aged 11 to 21 in the first few months of the pandemic, in comparison to the same months of 2019[7].

According to a report by the CDC, “Beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health–related ED visits among all pediatric ED visits increased and remained elevated through October. Compared with 2019, the proportion of mental health–related visits for children aged 5–11 and 12–17 years increased approximately 24%. and 31%, respectively”[8].

Researchers suggested that the disruption of in-person mental health care services, which normally take place at home or in school, and that arose as a result of pandemic-related measures, could be one factor contributing to the increase in suicide attempts during 2020. In addition, school closures may have contributed to this by reducing the ability of school counselors to reach out to students in vulnerable situations.

However, given the rise in suicide rates that commenced in previous consecutive years, there isn’t evidence that allows us to confidently attribute an increase in the youth suicide rate in 2020 solely to the COVID-19 pandemic, as there may be other factors involved. As noted, suicide rates are not the same for different demographic or ethnic groups. Furthermore, it is still too early to know the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the population, which would manifest only later down the road.

Paul’s claim that “more children have died by suicide than by COVID” is likely correct based on previous years’ figures, but it should be noted that the suicide rate in teens in the U.S. was already at a record high before the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, figures on child suicides in the U.S. must be interpreted within the context of the previous trend.

By focusing on the negative impact that lockdowns and school closures can have on children’s mental health, we lose sight of the public health benefits of these measures, which reduced the spread of COVID-19 and saved lives[1].

A study conducted in 11 European countries found that lockdowns reduced COVID-19 transmission by 81%[9]. Another study conducted in European countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Germany) found that school closures reduced the rate of infection and the number of hospitalizations seven days after implementation[10]. Similarly, it was found that early application of school closing in some states between March and May 2020 was temporally associated with a reduction in incidence and mortality of COVID-19. One caveat of the study is that the authors weren’t able to determine if school closures specifically were responsible for the reduction in COVID-19 cases, since school closures occurred in parallel with other interventions, such as lockdowns[11].

Seen from another perspective, reducing the number of illnesses and deaths occurring in the community may actually protect children’s mental health to some degree, for instance, by preventing illness and death among their family and friends.

Conclusion

Preliminary data show a 5.6% decrease in the overall suicide rate in the U.S. in 2020, although the trend over the past 20 years showed a steady increase. This could be due to a transient effect detected after previous natural catastrophes, known as the “pulling together” phenomenon. It is important to note that the long-term impact of the pandemic on the suicide rate may only manifest later down the road. The actual suicide rates for 2020 remain unknown due to a lack of data.

Although there is still no official national data on the impact that school closures have had on suicides in children, there is evidence suggesting that school closures help to limit COVID-19 transmission and save lives[10,11]. Paul’s statements downplay the positive impact of these measures, implying that these have a solely negative effect on children.

In conclusion, suicide rates in children in the U.S. were already at record high before the pandemic, and preliminary information suggests that this trend has increased during 2020. The extent to which the measures taken to curb COVID-19 infections have affected child suicides is yet to be determined.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Mégarbane et al. (2021). Is Lockdown Effective in Limiting SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic Progression?-a Cross-Country Comparative Evaluation Using Epidemiokinetic Tools. Journal of General Internal Medicine.

- 2 – Gunnell et al. (2020). Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry.

- 3 – Pirkis et al. (2021). Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. The Lancet Psychiatry.

- 4 – Faust et al. (2021). Suicide Deaths During the COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Network Open.

- 5 – Taquet et al. (2021). Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. The Lancet Psychiatry.

- 6 – Taquet et al. (2021). 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. The Lancet Psychiatry.

- 7 – Hill et al. (2021). Suicide Ideation and Attempts in a Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19. Pediatrics.

- 8 – Leeb et al. (2020). Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

- 9 – Flaxman et al. (2020) Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature.

- 10 – Stage et al. (2021). Shut and re-open: the role of schools in the spread of COVID-19 in Europe. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

- 11 – Auger et al. (2020). Association Between Statewide School Closure and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in the US. Journal of the American Medical Association.