- Climate

Washington Post story puts recent weather extremes in accurate climate change context

Reviewed content

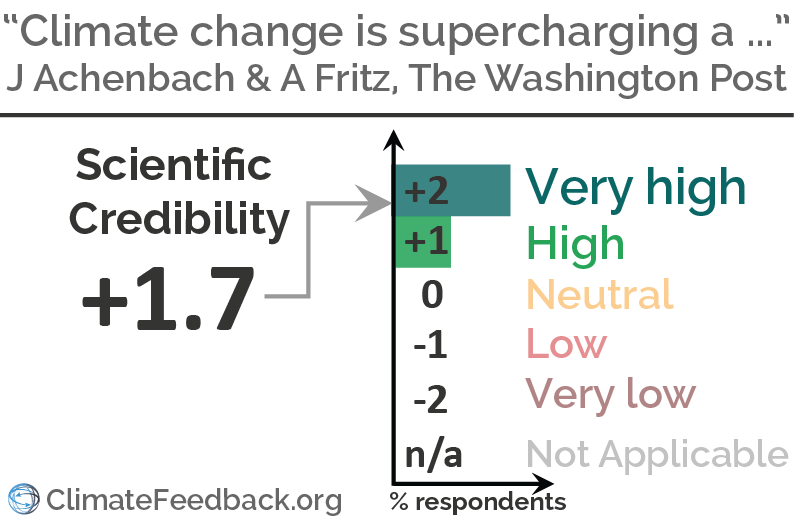

Headline: "Climate change is supercharging a hot and dangerous summer"

Published in The Washington Post, by Angela Fritz, Joel Achenbach, on 2018-07-26.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This story in The Washington Post lists a variety of extreme weather events seen around the Northern Hemisphere recently. The article explains that some of these types of weather are known to be connected to human-caused climate trends.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that this scientific context was accurately provided. Heatwaves and intense rainstorms, for example, are increasing in severity and frequency. Some weather patterns—like slow-moving meanders in the jet stream—are indeed less clear and consequently subjects of active research.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall assessment of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

This article accurately describes the broader climate context of recent heat extremes throughout the Northern Hemisphere. There are a couple spots where specific claims are somewhat stronger than justified by the existing scientific evidence, but in general the piece gives an accurate impression regarding the role of climate change and recent advances in extreme event attribution science.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

Climate change is supercharging a hot and dangerous summer

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

This is a reasonable title for the piece. While climate change is not the only factor in recent extreme and record-breaking heat, it is an important and pervasive one. The notion that climate change is “supercharging” heat extremes is an accurate one.

The brutal weather has been supercharged by human-induced climate change, scientists say. Climate models for three decades have predicted exactly what the world is seeing this summer. And they predict that it will get hotter — and that what is a record today could someday be the norm.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

Both of these statements are correct, and collectively emphasize two important points. First, the increasing frequency and intensity of heat extremes does indeed validate model-based and theoretical predictions from decades ago. Second, those same climate models suggest that what is today an extraordinary heat event could indeed become a “typical” temperature in future summers, depending on how much additional carbon society emits in the coming decades.

Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Research Center

True. More intense and prolonged heatwaves are directly connected to global warming. Heavier precipitation events are linked with additional water vapor in the atmosphere, which results from higher air temperatures (warmer air can hold more water vapor) and greater evaporation from ocean and land. Longer, more intense droughts are also clearly connected to global warming, as higher temperatures dry out soils earlier in spring and allow them to heat up faster. Climate models have long predicted a general increase in these extremes, and now we can refine those predictions for particular types of events, regions, seasons, and varying background conditions (such as El Niño).

Peter Gibson, Postdoctoral researcher, California Institute of Technology:

This is mostly correct. Regarding what models have predicted—it’s certainly the case that climate models have predicted a general increase in the frequency of heat waves as the world warms and there is a strong human influence. What is rather unique about this particular heat wave has been the spatial extent across the Northern Hemisphere. Basic statistics tells us that in a warming world the general likelihood of heatwaves coinciding at multiple locations would also increase (all else being equal). But another important piece of this puzzle is the particular jet stream configuration that also essentially acts to connect the heatwaves in multiple different regions together. An active area of research is understanding and improving how well some of these important mechanisms are represented in climate models.

It’s not just heat. A warming world is prone to multiple types of extreme weather — heavier downpours, stronger hurricanes, longer droughts.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

There is indeed scientific evidence that each of these types of extreme events is increasing (or will increase) in a warming world. However, the evidence is strongest for heatwaves and heavy downpours.

The proximate cause of the Northern Hemisphere bake-off is the unusual behavior of the jet stream, a wavy track of west-to-east-prevailing wind at high altitude. The jet stream controls broad weather patterns, such as high-pressure and low-pressure systems. The extent of climate change’s influence on the jet stream is an intense subject of research.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

This is accurate. So-called “atmospheric blocking” has occurred frequently this summer, and has historically been associated with extreme temperature and precipitation events.

Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Research Center

Also true. Many factors affect the jet stream’s strength and path, and recent studies are revealing several mechanisms by which climate change is playing a role. This summer the jet stream has undulated far north and south, and those large waves tend to remain locked in place for weeks, causing persistent weather patterns of various sorts. It’s no coincidence that severe heatwaves have occurred simultaneously in several locations (Japan, SW U.S., Greece, Scandinavia, Alaska) together with flooding in other locations and even cooler-than-normal temperatures elsewhere.

Peter Gibson, Postdoctoral researcher, California Institute of Technology:

This is an accurate reflection of where the science is at. I would point out that even if human fingerprints aren’t all over the dynamics of this event (i.e., the particular jet stream configuration) we know already that human fingerprints are all over the thermodynamics (i.e., the heatwave formed in an environment notably warmer than it would have been in the absence of human influence on the climate system).

Last year, scientists published evidence that the conditions leading up to “stuck jet streams” are becoming more common, with warming in the Arctic seen as a likely culprit.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

There have indeed been several recent publications suggesting that certain high-amplitude jet stream patterns have been occurring more frequently in recent years. There are also some hints that this could be related to enhanced high-latitude warming, but the potential causal linkages remain the subject of considerable ongoing scientific debate. At this point, there’s not yet consensus that the Arctic is a “likely” culprit, although it certainly is a suspect.

Gone are the days when scientists drew a bright line dividing weather and climate. Now researchers can examine a weather event and estimate how much climate change had to do with causing or exacerbating it.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

The field of “extreme event attribution” has indeed become much more prominent in recent years. This is a result of a combination of better modeling and analysis tools, plus a longer period of observed climate data from which to draw conclusions. While it is not possible to make these kind of attribution claims for all types of extreme weather events, it is increasingly true that this has moved from the margins to the relative mainstream of climate science.

Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Research Center

True, but perhaps a bit optimistic. In some cases the influence of climate change on a particular weather event can be estimated fairly well, but many times the extent of attribution is difficult to pin down. That said, scientists can now state much more confidently that certain types of extreme events are more or less likely now than in pre-industrial times, and often the amount of climate-related change can be quantified (e.g. twice as likely).

Peter Gibson, Postdoctoral researcher, California Institute of Technology:

This refers to event attribution (an important and growing subfield of climate science)—but it’s not always easy and there are some subtleties to this worth pointing out. Certainly, we can (and do) do this well for heatwaves, but it is still a major challenge for other types of extreme weather events today. Basically, events where the relevant physics need to be resolved at very high resolution (e.g. tornadoes and other very localized convective storms) are a major challenge for current day climate models used in these types of attribution studies. But our models are improving all the time so what is in the “hard basket” is constantly changing.

Overall precipitation has decreased in the South and West and increased in the North and East. That trend will continue.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

This statement is overly broad. Attribution of regional mean precipitation trends is still a challenging task in most places, with some exceptions.

The heaviest precipitation events will become more frequent and more extreme. Snowpack will continue to decline. Large wildfires will become even more frequent.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

These statements have much more robust support than the previous one.