- Climate

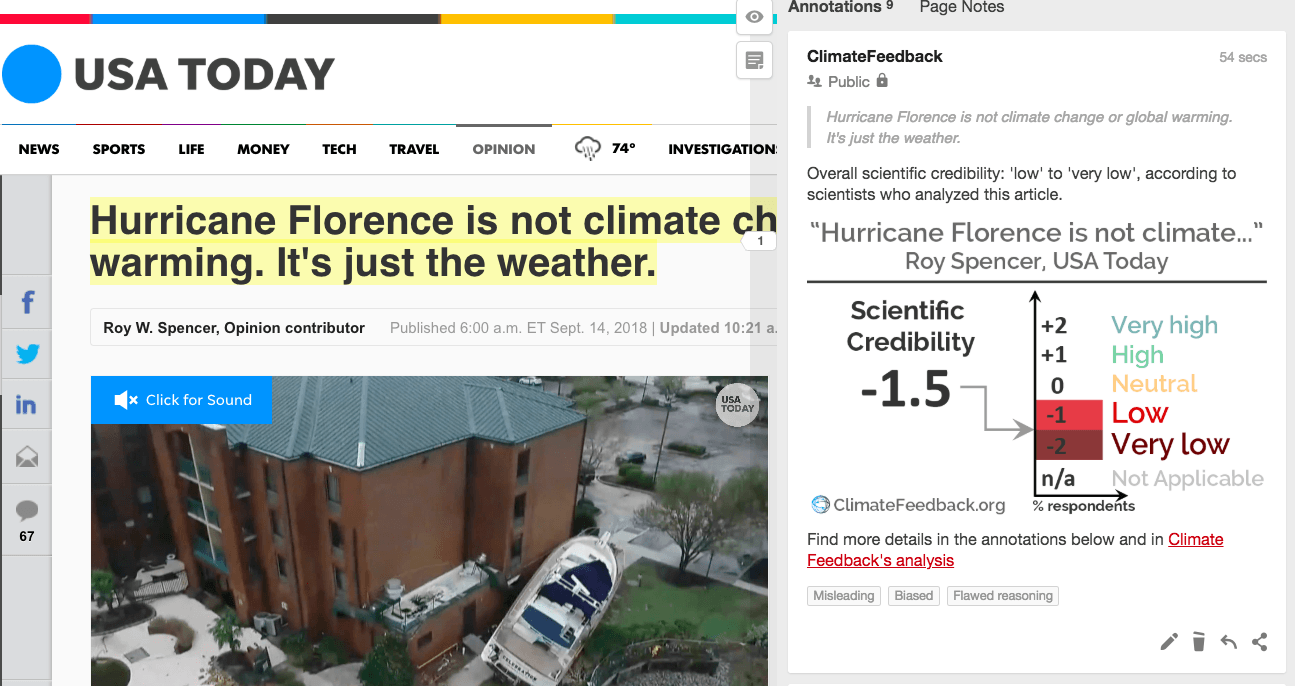

USA Today op-ed ignores evidence to claim climate change had no role in Hurricane Florence

Reviewed content

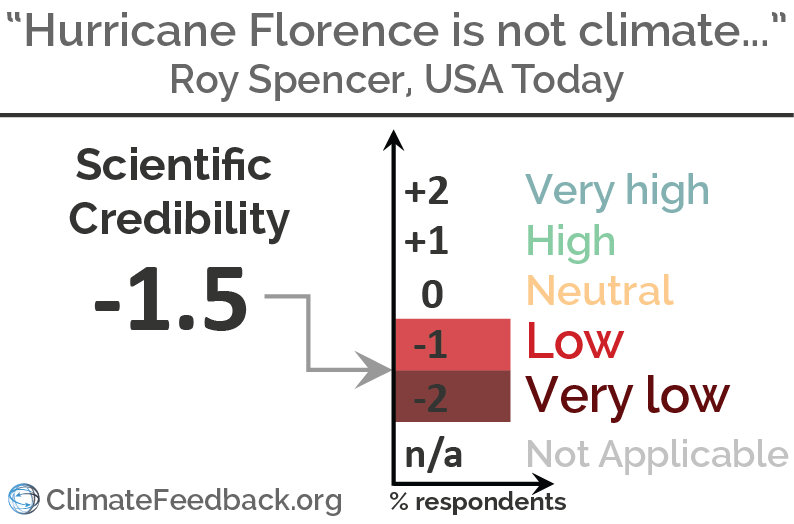

Headline: "Hurricane Florence is not climate change or global warming. It's just the weather."

Published in USA Today, by Roy Spencer, on 2018-09-14.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This op-ed in USA Today makes the claim that Hurricane Florence has no appreciable contribution from human-caused climate change.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that it ignores the evidence for trends in tropical cyclone behavior, including slower movement speed and more intense rainfall. Additionally, sea level rise raised the storm surge of the landfalling tropical cyclone above the level it would have reached a century ago. The article cherry-picks data in misleading way to claim that recent storms are no different from past tropical cyclones, but does not provide the analysis necessary to support this claim.

Published research on the topic does, in fact, show that climate change affects tropical cyclones like Florence. While it is unpublished and preliminary, an early analysis by researchers at Stony Brook University and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggested human-induced warming could have increased Florence precipitation near its maximum by up to 50%, and more extensive research showed it contributed 15%[1] to 20%[2,3] increased rainfall for Hurricane Harvey. This is due to the fact that warmer air can hold more water vapor[4], which increases hurricanes intensity and rainfall.

- [1] – van Oldenborgh et al (2017) Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017, Environmental Research Letters.

- [2] – Wang et al (2018) Quantitative attribution of climate effects on Hurricane Harvey’s extreme rainfall in Texas, Environmental Research Letters.

- [3] – Risser and Wehner (2017) Attributable Human‐Induced Changes in the Likelihood and Magnitude of the Observed Extreme Precipitation during Hurricane Harvey, Geophysical Research Letters.

- [4] – Wentz et al (2007) How Much More Rain Will Global Warming Bring?, Science.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context. You can also install the Hypothesis browser extension to read the scientists’ annotations in context.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall assessment of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Assistant Professor, Purdue University

The article’s principal argument is that a climate change effect on the speed of motion of a storm like Florence “is small, probably temporary, and most likely due to natural weather patterns”. But the author provides no evidence for this argument and ignores recent research providing clear evidence that 1) storms are slowing down in observations, and 2) that this is likely to continue in the future under climate change. Beyond this, the author makes various other statements that, whether accurate or inaccurate, are largely irrelevant to the topic of Florence.

Professor, Texas A&M University

The scientific community has developed analytic tools to determine to what extent a warming climate has affected hurricanes (e.g.*). Dr. Spencer’s position is not backed up by any analysis—rather, it’s the result he wishes were true. I wish we weren’t making hurricanes worse too, but I am convinced by the scientific analyses that we are.

- Holland and Bruyere (2013) Recent intense hurricane response to global climate change, Climate Dynamics.

- Walsh et al (2015) Tropical cyclones and climate change, WIREs Climate Change.

Professor, Florida State University

There are strong theoretical reasons to expect stronger hurricanes under global warming*. These reasons are ignored by the author.

- Kang and Elsner (2015) Climate Mechanism for Stronger Typhoons in a Warmer World, Journal of Climate.

- Knutson et al (2010) Tropical cyclones and climate change, Nature Geoscience.

- Sobel et al (2016) Human influence on tropical cyclone intensity, Science.

Professor of Atmospheric Science, MIT

The article trots out the time-worn non sequitur that since climate has changed in the past we need not worry about it changing in the future.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Annotations

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

The theory is that tropical cyclones have slowed down in their speed by about 10 percent over the past 70 years due to a retreat of the jet stream farther north, depriving storms of steering currents and making them stall and keep raining in one location.

This is not based on theory but on solid observational data* that show that tropical cyclone translation speeds have been decreasing.

- Kossin (2018) A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed, Nature

But like most claims regarding global warming, the real effect is small, probably temporary, and most likely due to natural weather patterns

Three independent peer-reviewed studies* of Hurricane Harvey concluded that the probability of hurricane rains of that magnitude in Houston have already increased by factors of 2-3 since the middle of the 20th century. These are not small changes.

- Emanuel (2017) Assessing the present and future probability of Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall, PNAS

- van Oldenborgh et al (2017) Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017, Environmental Research Letters

- Risser and Wehner (2017) Attributable Human‐Induced Changes in the Likelihood and Magnitude of the Observed Extreme Precipitation during Hurricane Harvey, Geophysical Research Letters

Coastal lake sediments along the Gulf of Mexico shoreline from 1,000 to 2,000 years ago suggest more frequent and intense hurricanes than occur today.

It is true that coastal lake sediments indicate more risk in certain places than can be assessed with the very short and poor historical records. The authors of at least one of these studies attributed this not to climate change but to the problems of assessing current risk using only the historical record.

- Liu and Fearn (2000) Reconstruction of Prehistoric Landfall Frequencies of Catastrophic Hurricanes in Northwestern Florida from Lake Sediment Records, Quaternary Research

The Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635 experienced a Category 3 or 4 storm, with up to a 20-foot storm surge. While such a storm does not happen in New England anymore, it happened again there in 1675, with elderly eyewitnesses comparing it to the 1635 storm.

This is highly misleading and inaccurate. Most evidence points to three major events of comparable magnitude in New England, in 1635, 1815, and 1938. Major New England hurricanes are far too rare to pick out any climate signal. But this does not mean that the underlying probabilities are not changing. The flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy would likely not have occurred without the increase in sea level that has demonstrably taken place since the city’s early history.

Nine years into that 11-year hurricane drought, a NASA scientist computed it as a 1-in-177-year event.

The paper the author quotes concluded that “A hurricane climate shift protecting the U.S. during active years, even while ravaging nearby Caribbean nations, would require creativity to formulate. We conclude instead that the admittedly unusual 9 year U.S. Cat3+ landfall drought is a matter of luck.”

- Hall and Hereid (2015) The frequency and duration of U.S. hurricane droughts, Geophysical Research Letters.

Well, aren’t we being told these storms are getting stronger on average? The answer is no. The 30 most costly hurricanes in U.S. history (according to federal data from January) show no increase in intensity over time.

U.S. landfalling hurricanes constitute only about 4% of all tropical cyclones, and landfall occupies only a small percentage of their lifetimes. Examination of global data does suggest some increase in tropical cyclone intensity*, along the lines of predictions made 30 years ago.

- Elsner et al (2008) The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature

- Webster et al (2005) Changes in Tropical Cyclone Number, Duration, and Intensity in a Warming Environment, Science.

The monetary cost of damages has increased dramatically in recent decades, but that is due to increasing population, wealth and the amount of vulnerable infrastructure. It’s not due to stronger storms.

The main problem in the U.S. and many other places is unwise policy that encourages coastal development. Lawmakers have tried to change such policies only to get strong push-back from coastal property owners, whom the rest of us are forced to subsidize. While I agree with the author that this is the most important problem, it is being compounded by climate change, including sea-level rise.

If humans have any influence on hurricanes at all, it probably won’t be evident for many decades to come

In many metrics, it is already evident (e.g. for rain*). Waiting for the signal to emerge unambiguously before acting would be foolish, particularly when, by then, it would be too late. No battlefield general would ever take such a position. Damage and loss of life from weather hazards is done mainly by events rare enough that human society has not adapted to them. The incidence of such rare events is affected disproportionately by climate change, even while changes in such rare events are, by definition, hard to detect in historical data. Mitigating risk means acting on the best available evidence, and the best scientific evidence available suggest that hurricane risks will increase quite substantially as the climate warms.

- Emanuel (2017) Assessing the present and future probability of Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- van Oldenborgh et al (2017) Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017, Environmental Research Letters.