- Health

Sweden’s COVID-19 mortality is higher than in most European countries; no evidence whether or how the absence of lockdown impacted this outcome

Key takeaway

An analysis of COVID-19 mortality rates shows that Sweden is one of the worst-performing countries in Europe, although Italy, Spain, and the U.K. have experienced higher rates. Countries like Sweden that did not implement lockdowns show a range of mortality rates, making it difficult to determine whether Sweden’s policies had any impact, either positive or negative in the COVID-19 epidemic outcome.

Reviewed content

Verdict detail

Cherry-picking: The article compared the COVID-19 mortality rate in Sweden, which did not implement a lockdown, to European countries which did implement lockdowns but experienced higher mortality rates. Inexplicably, the article excluded countries that implemented lockdowns and experienced lower mortality rates.

Misrepresents a complex reality: Comparing epidemiological outcomes between countries is difficult and in most cases uninformative. This is because countries can differ widely in terms of economics, demographics, and politics, all of which can affect the health and economic consequences of the pandemic on a country. It is thus too simplistic to infer from a comparison of mortality whether lockdowns are an effective strategy for reducing COVID-19 mortality rates.

Full Claim

“Sweden COVID-19 Death Rate Lower Than Spain, Italy and U.K., Despite Never Having Lockdown”

Review

An article published in Newsweek on 3 August 2020 reported on the evolution of the COVID-19 epidemic in Sweden. Based on information gathered from multiple databases, including John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center and the World Health Organization COVID-19 situation reports, the article claims that Sweden, which never had a lockdown, had a lower COVID-19 mortality rate than certain European nations that had implemented lockdowns, specifically Spain, Italy, and the U.K. It claims that the country “continues to report a downward trend in new [COVID-19] cases and new deaths” even though Sweden never issued “a countrywide lockdown”.

The repeated juxtaposition of the absence of a lockdown and the seemingly better epidemiological outcome in Sweden misleadingly suggests to the reader that lockdowns have not been useful or effective in curbing the spread of the disease. While the figures supporting the claim are accurate, a lack of context as well as the cherry-picking of countries used in the comparison is blurring the take-home message and leading to biased conclusions.

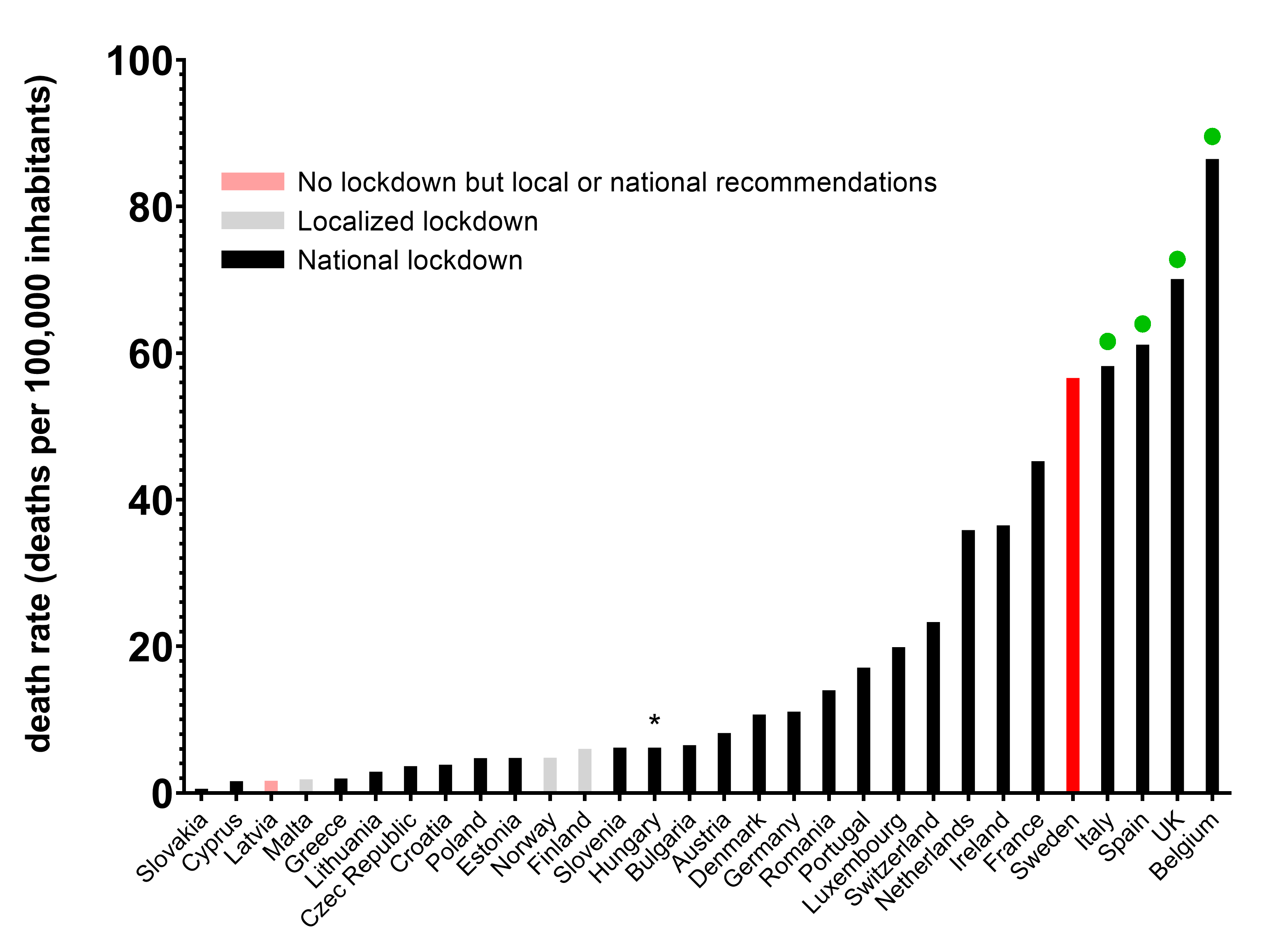

Firstly, the article compared countries’ death rates, which are defined as the number of COVID-19-related deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. Based on data collected by Johns Hopkins University, the Swedish death rate is approximately 56 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. This number is lower than the rates in Spain, Italy, Belgium, and the U.K., all countries which implemented lockdowns to some extent. Although the number is accurate, the article does not explain why it selected these specific countries for comparison and not others.

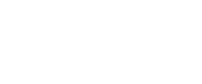

Here, Health Feedback pursued a more comprehensive approach to analyzing the data. We used the same mortality dataset from Johns Hopkins University on its 12 August 2020 update to rank all European Union (E.U.) countries plus Switzerland, Norway, and the U.K. expressed as number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. We also noted which countries had implemented nationwide lockdowns, local lockdowns, or merely provided recommendations; these determinations are based on a classification performed by the BBC (Figure 1).

Figure 1: COVID-19 mortality for countries in the E.U. plus Switzerland, Norway, and the U.K. expressed as the number of COVID-19-related deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. Death rates are from Johns Hopkins University. Lockdown policies per country are from the BBC. Sweden is shown in red. Countries in black have enforced nationwide lockdowns. Countries in grey have enforced local lockdowns. Countries in light red have not enforced lockdowns. Green dots indicate the countries that the Newsweek article compared to Sweden. * Hungary was classified in the “no lockdown” category by the BBC, but in fact Hungary did implement a lockdown.

As shown in Figure 1, Sweden has one of the highest death rates of the 30 European countries included in our analysis. In fact, Spain, Italy, the U.K., and Belgium are the only countries with higher death rates than Sweden. Most of the other countries present a better outcome and the majority have implemented a full or partial lockdown. Although the article claimed to have made a comparison of COVID-19 deaths between Sweden and the rest of Europe, the author did not compare Sweden to all European countries and only included countries that performed poorly compared to Sweden, which are indicated by the green dots in Figure 1.

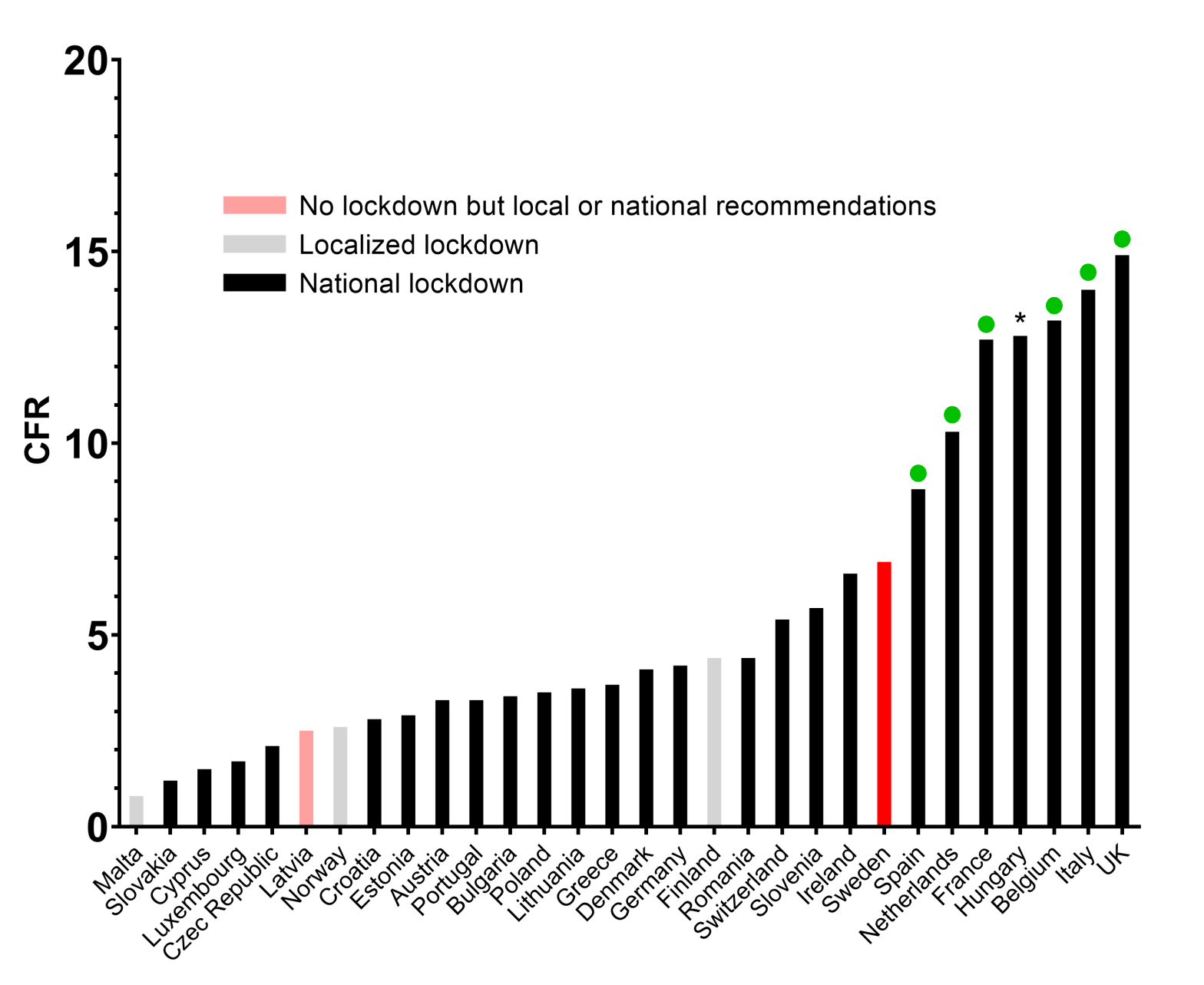

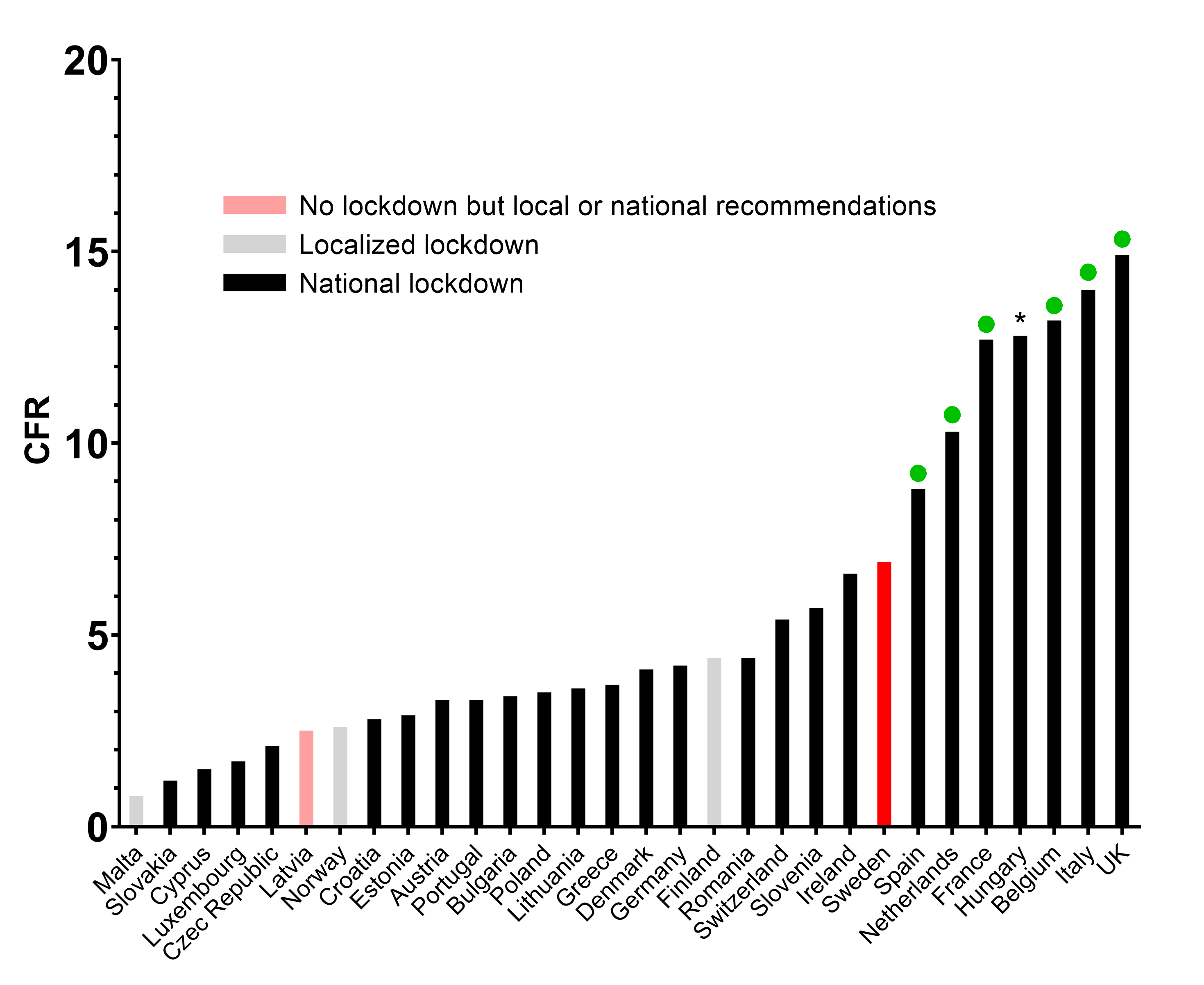

Secondly, the article compared the case fatality ratio (CFR) of Sweden to Belgium, Spain, Italy, France, the Netherlands, and the U.K. CFR is the number of COVID-19-related deaths as a proportion of the total number of confirmed cases. The article accurately reports that Sweden has a lower CFR compared to these countries, which had all implemented lockdowns. However, the CFR is highly dependent on parameters such as the quality of the local health care system, demographics, and testing policies. Therefore, a comparison of CFRs between countries does not accurately reflect how successfully a country is battling the COVID-19 outbreak based on its policies.

Despite claiming to compare Sweden’s CFR to the rates in “Europe”, the comparison once again only included a few of the many European countries currently fighting the pandemic, and the article fails to explain why only certain countries were chosen. When Health Feedback compared all countries in the E.U., along with the U.K., Switzerland, and Norway, Sweden ranked 8th highest on the list of CFRs for 30 countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Case fatality ratio for countries in the E.U., plus Switzerland, the U.K., and Norway. Mortality rates are from Johns Hopkins University. Lockdown policies per country are from the BBC.Sweden is shown in red. Countries in black have enforced nationwide lockdowns. Countries in grey have enforced local lockdowns. Countries in light red have not enforced lockdowns. Green dots indicate the countries that the Newsweek article compared to Sweden. * Hungary was classified in the “no lockdown” category by the BBC, but in fact Hungary did implement a lockdown.

Figure 2 demonstrates that most of the countries which exhibit a lower CFR than Sweden have implemented lockdowns. But the Newsweek article only compared Sweden with countries that had a higher CFR than Sweden. It is unclear why the article excluded Hungary from its analysis. In summary, the countries chosen for the comparison appear to show Sweden in a more favorable light than would have occurred had Sweden been compared to all European countries instead. Whether by accident or design, the article’s arbitrary selection of countries produces the misleading impression that lockdowns do not work.

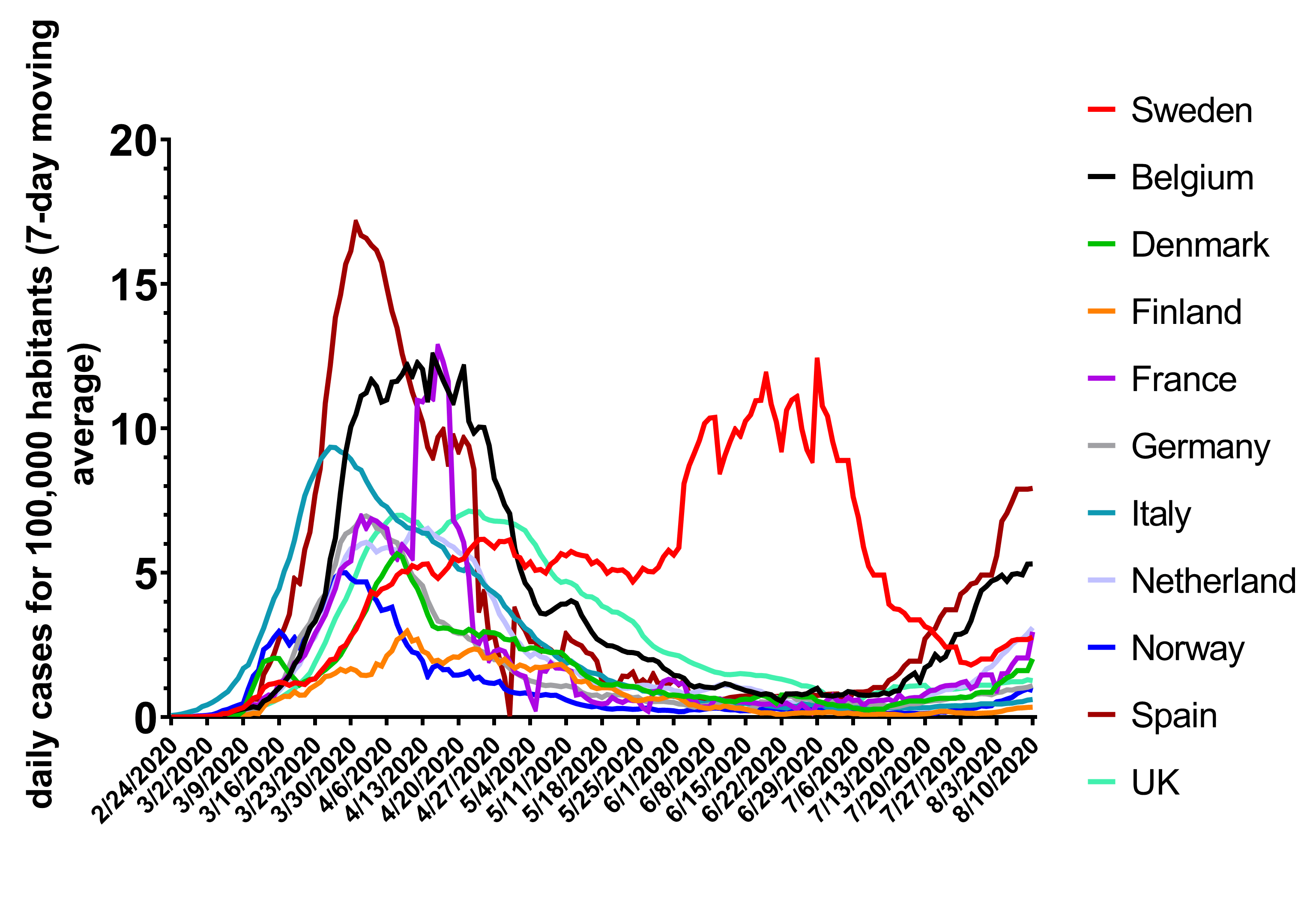

Thirdly, the authors compared the number of newly detected COVID-19 cases in Sweden to other countries. It is difficult to get an idea of the evolution of an epidemic using this metric because it is strongly influenced by the size of the population and the country’s testing policy. For example, if the number of tests carried out increases greatly from one week to another, the absolute number of positive tests would likely also increase, leading to the potentially false impression that the positivity rate—the proportion of positive tests to the total number of tests carried out—is increasing.

Nevertheless, the author of the Newsweek article used absolute numbers from a 14-day period through 2 August and compared them to the previous 14-day period, claiming that the data show a decreasing trend in Sweden relative to other countries. It is unclear whether the author compared the cumulative number of new cases from these 14-day periods or performed a day-to-day comparison. Regardless, a more useful way to monitor the evolution of the number of new cases reported daily is to use a moving average in order to smooth out day to day variations. Figure 3 shows the 7-day moving average of new cases as reported in the Github repository of the Center for System Sciences and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, normalized to each country’s population.

Figure 3: Evolution of the daily number of new COVID-19 cases in the countries chosen for comparison in the Newsweek article. The data were retrieved from the Github repository of the Center for System Sciences and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. Data are normalized by the population of each country and smoothed by a 7-day moving average.

We used a similar data analysis approach to that used by the article’s author. The results using this method suggest that the Newsweek article accurately determined that countries such as Belgium and Spain are experiencing a second wave of new cases in July and August 2020. However, Sweden is also seeing an increase in new cases that is similar to France, Denmark, and the Netherlands. It is therefore misleading to suggest that the number of new infections in Sweden is decreasing while the number is increasing in other countries. In reality, as reported by The Public Health Agency of Sweden, the positivity rate increased slightly in the last two weeks compared with the previous two weeks.

As the BBC noted, it is difficult to compare the epidemiological metrics of different countries, especially while the pandemic is unfolding. For instance, the CFR highly depends on the testing policy implemented by a country. A country that only tests hospitalized patients may end up with a higher CFR than a country that systematically tests everybody, including asymptomatic patients, because hospitalized patients tend to be sicker than outpatients and are therefore more likely to die from their illness.

A more accurate way to estimate COVID-19’s impact on mortality is to calculate all-cause mortality in 2020 compared to the average of previous years. Any increase from previous years is referred to as “excess mortality”. Given that this metric looks at the total number of deaths in a country or region due to all causes, it is not affected by the aforementioned differences in testing policies.

Assuming that all other parameters that may impact mortality have remained relatively stable over the past couple of years, it is likely that any excess mortality in 2020 can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Economist examined the total number of deaths in several different countries in 2020 compared to the average of the 2009 – 2019 decade. The analysis showed that although Sweden’s excess mortality in 2020 was lower than in Italy and France, it was higher than in many other countries, including those with enforced lockdowns such as Portugal and Denmark.

Finally, cultural factors may influence how different populations behave in the midst of a pandemic, independently of policies made by health authorities. For example, in an article published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Eric Orlowski and David Goldsmith from the University College London write that the adherence of Swedish citizens to physical distancing even in the absence of nationwide enforcement may be deeply rooted in their culture. The BBC reported in July 2020 that Sweden’s chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, found that social interactions among Swedish citizens have declined to about 30% of what they were before the epidemic, and that more than 80% of the population still follows physical distancing practices. This demonstrates that it is impossible to conclude whether two countries with the same lockdown measures but with different cultural practices would adhere to physical distancing to the same degree or would experience the same effects of the lockdown measures.

In summary, the Newsweek article reports accurate numbers but they are cherry-picked to suggest that Sweden is less affected by the COVID-19 epidemic than other countries in Europe. The article excluded all countries from its comparison with a lower CFR than Sweden even though it claims to have conducted comparisons between Sweden and the rest of Europe. This is misleading the reader into concluding that lockdowns are ineffective. In addition, mortality rates in different countries can not be compared directly because they ignore differences in multiple variables, such as cultural background, which can significantly alter the impact or necessity of a lockdown.

UPDATE (21 Aug 2020):

After our evaluation was published, Newsweek corrected their article to provide additional context for readers, by including more European countries in the CFR and mortality rate comparisons. The article also now explicitly states that Sweden still suffers from one of the highest death rates in Europe and warns readers of the difficulty of making comparison of death rates between countries owing to potential confounding variables.

UPDATE (18 Aug 2020):

Corrections were made to account for the fact that Hungary should have been listed as implementing a lockdown, as confirmed by different news outlets such as Reuters. These corrections were made in the Details, Figure 1, and Figure 2. We also clarified that comparing daily absolute numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases between countries, as the author of the Newsweek article did, does not yield useful results because the metric is too sensitive to the testing policy employed in each country. The proportion of tests returning a positive result out of the total number of tests conducted, known as the positivity rate, increased in Sweden in early August compared with the previous two weeks, so the virus circulation is not likely to have decreased as the Newsweek article suggests.