- Climate

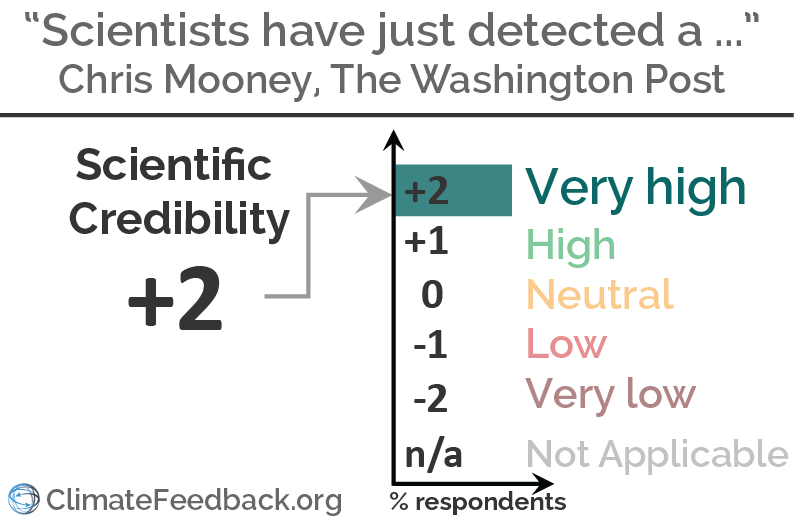

Analysis of "Scientists have just detected a major change to the Earth’s oceans linked to a warming climate"

Reviewed content

Published in The Washington Post, by Chris Mooney, on 2017-02-15.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This article in The Washington Post details a new study that compiled oxygen concentration measurements in the ocean from all over the world, showing a detectable global decrease of a little more than 2% since 1960. While the study does not definitively evaluate the cause of the observed decrease, this is an expected consequence of ocean warming.

According to the scientists who reviewed the article, it accurately represents research on the topic—including clear and measured descriptions of the negative impacts of oxygen trends on marine life.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

This is part of a series of reviews of 2017’s most popular climate stories on social media.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

CNRS Senior scientist, Université Pierre et Marie Curie

The content of the article is correct. It reports on a new study in Nature showing the first observational evidence of a diminution of oxygen levels in the oceans at a global scale. This is in agreement with projections from climate models. In some regions where oxygen concentrations are already low, this can be critical for ecosystems.

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

Changes in ocean chemistry, temperature, and circulation have significant consequences for marine life and can initiate positive feedbacks to accelerate ocean and atmosphere warming. This article is refreshing in that the author presents the results and significance of global ocean oxygen loss accurately and very clearly for non-expert audiences.

Postdoctoral Research fellow, Sorbonne University

This is a very good article which includes an interview with the first author as well as comments from two other researchers (Matthew Long and Denis Gilbert) who work on oxygen. The article is very accurate and the author does not exaggerate, but tries to explain several details.

Postdoctoral Research Associate, MIT

This article was well substantiated and measured in its reporting of the decline in global ocean oxygen concentrations, without being hysterical about the potential for mass fish suffocations, which I have seen in previous articles on this subject. Several quotes were from scientists not involved in the research paper, which lends credibility. Shame that the headline is not entirely transparent about the content of the article. The content does support the headline, but I would still consider this clickbait.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“A large research synthesis, published in one of the world’s most influential scientific journals, has detected a decline in the amount of dissolved oxygen in oceans around the world — a long-predicted result of climate change that could have severe consequences for marine organisms if it continues.”

Professor of Biology, Stanford University, Hopkins Marine Station

It has been clear for at least 10 years that oxygen has been declining in the world’s oceans, both in near-surface waters and at depth, particularly in those areas with strong, natural oxygen-minimum-zones. This new study greatly extends analyses of historical data to include a significantly longer time period, a much broader global area, and to the entire water column—from the surface to 6,000 meters [depth]. This volume represents most of the inhabitable volume of the planet, and what happens there impacts all organisms, including humans, that inhabit the thin skin of terra firma.

“But as that upper layer warms up, the oxygen-rich waters are less likely to mix down into cooler layers of the ocean because the warm waters are less dense and do not sink as readily.”

Research Scientist, University of California, Merced

Enhanced stratification of the water column is indeed one mechanism that can explain the decrease in subsurface oxygen, notably in the tropics[1].

As the upper-layer of the ocean warms faster than the deeper layers, the temperature stratification increases, with the already-warm upper layer getting warmer. This enhanced thermal stratification acts as a barrier to vertical mixing, since warmer water is less dense (like when a low density fluid (e.g. oil) tops a high density fluid (e.g. water)). This stratification can prevent oxygen coming from the surface from reaching deeper layers where it gets depleted by biological activity (respiration).

As climate change proceeds, the upper-ocean layer is also expected to become fresher (less salty) in the tropics as rainfall increase, further increasing the upper-ocean stratification[2].

- [1] Behrenfeld et al (2006) Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity. Nature

- [2] Balaguru et al (2016) Global warming-induced upper-ocean freshening and the intensification of super typhoons. Nature Communications

“‘Natural variations have obscured our ability to definitively detect this signal in observations,’ Long said in an email. ‘In this study, however, Schmidtko et al. synthesize all available observations to show a global-scale decline in oxygen that conforms to the patterns we expect from human-driven climate warming. They do not make a definitive attribution statement, but the data are consistent with and strongly suggestive of human-driven warming as a root cause of the oxygen decline.’”

Postdoctoral Research fellow, Sorbonne University

It’s very good that the difficulties in detecting the signal of declining oxygen are mentioned by citing a researcher. Also the very cautious statement on the reasons are good. No unnecessary panic mongering.

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

This is supported by the relatively rapid (sub-decadal to decadal) changes in global ocean oxygen loss that are consistent with rapid changes in atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions and associated warming effects on the atmosphere and ocean, when compared to the longer-term context recorded in geological archives of past ocean variability.

“Because oxygen in the global ocean is not evenly distributed, the 2 percent overall decline means there is a much larger decline in some areas of the ocean than others.”

Postdoctoral Research Associate, MIT

I think this is a subtle and important point to make—2% globally might not seem that much but there will be areas where the decline is more significant, such as the boundaries of Oxygen Minimum Zones, where waters could go from habitable to uninhabitable.

“Moreover, the ocean already contains so-called oxygen minimum zones, generally found in the middle depths. The great fear is that their expansion upward, into habitats where fish and other organism thrive, will reduce the available habitat for marine organisms.”

Professor of Biology, Stanford University, Hopkins Marine Station

Expansion of naturally occurring oxygen-minimum-zones, particularly the world’s largest in the eastern Pacific Ocean, is becoming more and more firmly established over a vast region at depths of several hundred meters. What’s important—and counter-intuitive—about these oxygen-minimum-zone regions is that they tend to be dynamic features of some of the most productive upper-ocean areas on Earth. The Humboldt Current system off South America supports the world’s largest single-species fishery (Peruvian anchovetta) but has water with extremely low oxygen concentration in near-shore fishing zones at depths of less than 100 meters. Any vertical (upwards) expansion of this oxygen-minimum-zone will compress the surface layer where anchovetta as well as their predators (including human fishers) operate. Increasing the density of predator and prey in a shrinking volume seldom produces a pretty result. It’s not just a matter of reduced habitat for individual species—it’s more like putting an entire highly productive ecosystem into a trash compactor.

“At the end of the current paper, the researchers are blunt about the consequences of a continuing loss of oceanic oxygen. ‘Far-reaching implications for marine ecosystems and fisheries can be expected,’ they write.”

Professor of Biology, Stanford University, Hopkins Marine Station

Potential biological consequences of the trends in ocean deoxygenation documented are, if anything, understated. This is really serious business. We have done a fair job at increasing public awareness of ocean acidification, and we need to do that with deoxygenation as well. The scary thing is we know very little how these two phenomena (low pH and low oxygen) work together to impact animals that live in the ocean—from plankton to predators. When you add increasing temperature to this mix, it is clear that we have a lot to learn.

Postdoctoral Research fellow, Sorbonne University

It’s true that this is the last sentence of the paper. However, they refer to another study here:

- Cheung et al (2012) Shrinking of fishes exacerbates impacts of global ocean changes on marine ecosystems. Nature Climate Change.

“warmer oceans have also begun to destabilize glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica”

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

This is especially true for marine-terminating glaciers, meaning that the seaward-most margin of the glacier rests on a bed below sea level and, therefore, in direct contact with the ocean. Examples are glaciers in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica such as Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers*, currently experiencing rapid retreat that is associated with warm ocean water melting the glaciers and their floating ice shelves.

- Jacobs et al (2011) Stronger ocean circulation and increased melting under Pine Island Glacier ice shelf. Nature Geoscience

- Shepherd et al (2004) Warm ocean is eroding West Antarctic ice sheet. Geophysical Research Letters

“On top of all of that, declining ocean oxygen can also worsen global warming in a feedback loop. In or near low oxygen areas of the oceans, microorganisms tend to produce nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas, Gilbert writes.”

Research Scientist, University of California, Merced

Another “positive feedback loop” related to ocean warming and increased stratification is that this can reduce the ocean CO2 uptake, by preventing CO2 from being mixed down into the deep ocean layers.

- Matebr and Hirst (1999) Climate change feedback on the future oceanic CO2 uptake. Tellus