- Climate

Robust scientific evidence supports that human activity drives global warming, contrary to claims in a CO2 Coalition blog post by Andy May

Key takeaway

All available scientific evidence, including independent physical observations, indicates that global warming is driven by human greenhouse gas emissions and that solar forcing plays an extremely minor role in contemporary climate.

Reviewed content

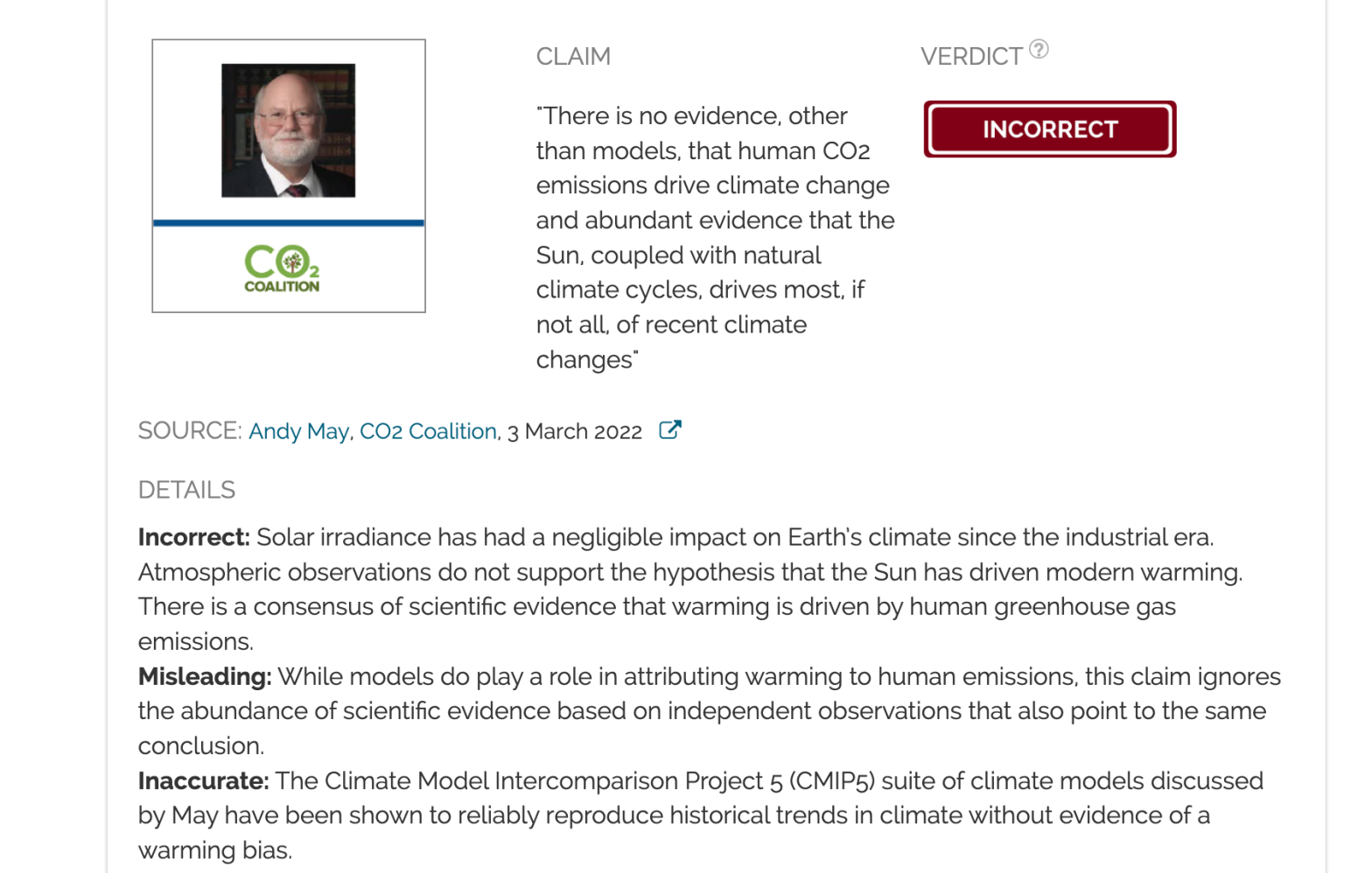

Verdict:

Claim:

"There is no evidence, other than models, that human CO2 emissions drive climate change and abundant evidence that the Sun, coupled with natural climate cycles, drives most, if not all, of recent climate changes"

Verdict detail

Incorrect: Solar irradiance has had a negligible impact on Earth’s climate since the industrial era. Atmospheric observations do not support the hypothesis that the Sun has driven modern warming. There is a consensus of scientific evidence that warming is driven by human greenhouse gas emissions.

Misleading: While models do play a role in attributing warming to human emissions, this claim ignores the abundance of scientific evidence based on independent observations that also point to the same conclusion.

Inaccurate: The Climate Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) suite of climate models discussed by May have been shown to reliably reproduce historical trends in climate without evidence of a warming bias.

Full Claim

"There is no evidence, other than models, that human CO2 emissions drive climate change and abundant evidence that the Sun, coupled with natural climate cycles, drives most, if not all, of recent climate changes"

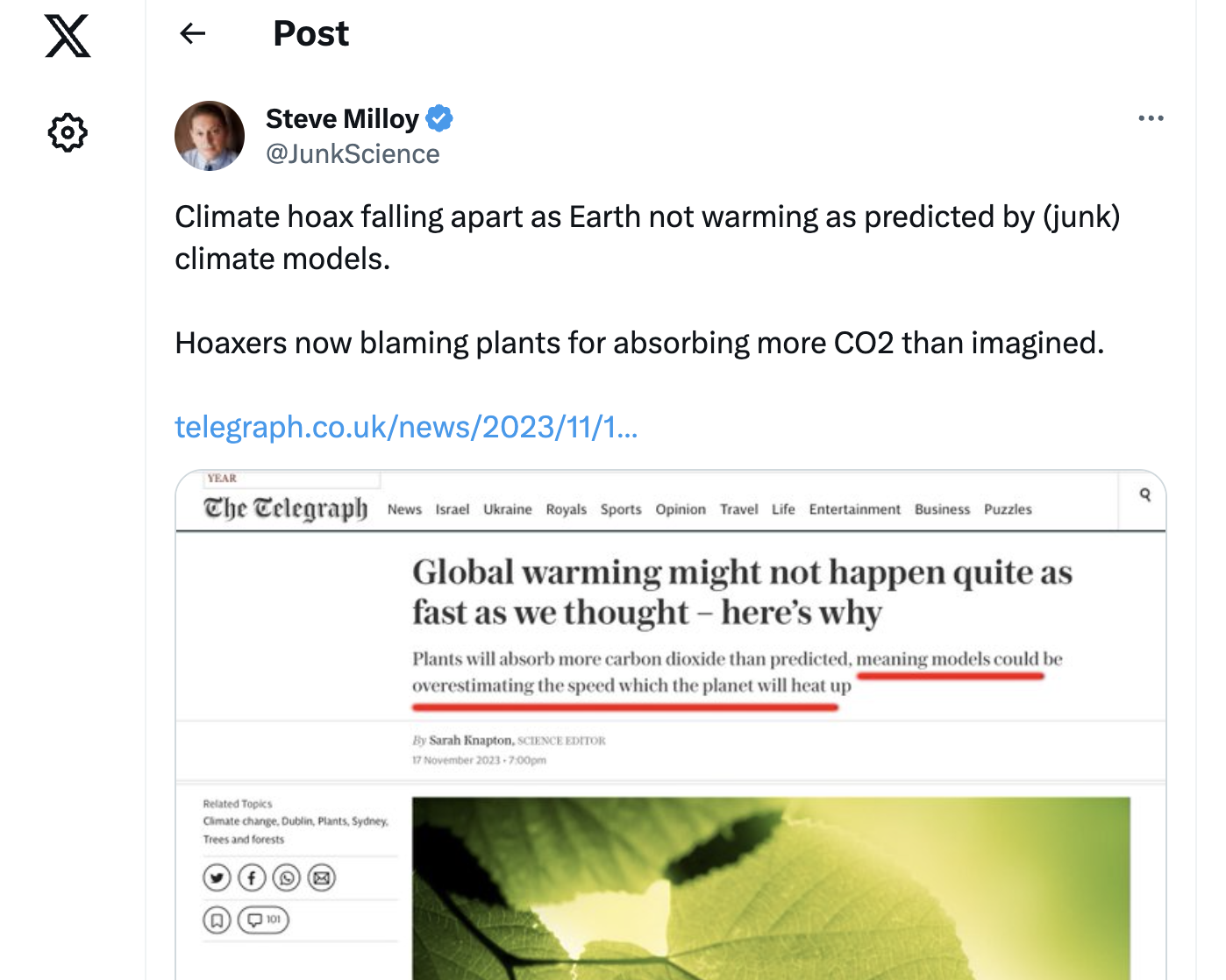

A recent blog post by Andy May published by the CO2 Coalition, a nonprofit organization funded largely by fossil-fuel interest groups, claims that the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)[1] relies upon model evidence to conclude that greenhouse gas emissions, such as CO2, drive contemporary global warming. May, who presents himself as a retired geologist, goes on to say that these models employ “circular proof” to attribute warming to CO2 emissions and argues that there is “abundant evidence that the Sun, coupled with natural climate cycles, drives most, if not all, of recent climate changes”, rejecting the consensus of scientific evidence that global warming is caused by human greenhouse gas emissions[2-5]. The “abundant evidence” that May invokes is a single article published in a journal unrelated to climate science by Connolly et al. (2021), which uses simple linear regression (itself a basic statistical model) to establish links between solar irradiance and the surface temperature of select northern-hemisphere locations.

“It is ironic…that they consider these fairly rigorous and physical model-based methods [of the IPCC] to be disqualifying and yet in the next sentence celebrate Connolly et al’s (2021) ‘simple linear regression’ of surface temperature records against total solar irradiance [which is also a model] as ‘abundant evidence’ that the Sun drives climate change,” commented Henri Drake, a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University and NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

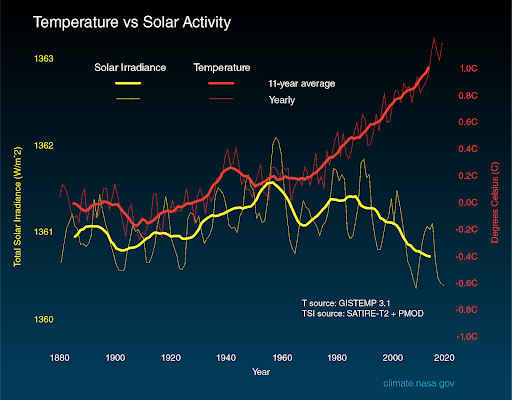

Moreover, observations indicate that solar irradiance has actually decreased since the 1960s, which is in clear contrast to the increasing trend in global surface temperature, showing that the Sun could not have driven warming during this period (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Comparison of the global surface temperature time series (red) and the Sun’s energy that Earth receives (yellow) in watts per square meter since 1880. One can see that since the 1960s, the global temperature and solar activity have varied in opposite directions. Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

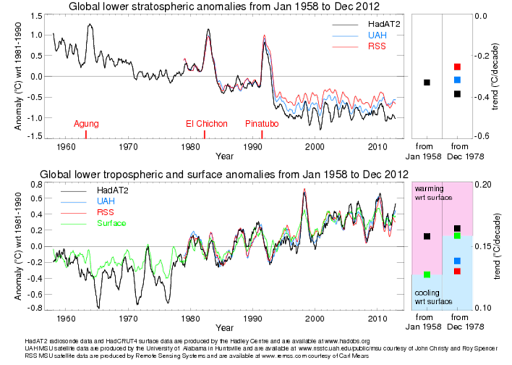

Another reason why scientists know that the Sun is not responsible for modern warming can be found in atmospheric observations. Greenhouse gases absorb heat in the form of infrared radiation in the lower atmosphere (troposphere), resulting in warming of the planet’s surface and lower atmosphere. By contrast, greenhouse gases produce a cooling effect on the upper atmosphere (stratosphere), making the offset between the temperature in the troposphere and stratosphere a useful “fingerprint” of global warming caused by emissions[6-9]. Such a temperature offset between the lower and upper atmosphere is not expected from warming driven by solar irradiance, as this mechanism increases the temperature of the entire atmosphere. Atmospheric observations indicate that the troposphere has warmed while the stratosphere has cooled over the last several decades (Figure 2), in line with expectations of warming driven by greenhouse gases.

Figure 2. Global temperature variations in the upper atmosphere (top graph) and in the lower atmosphere (bottom graph) since the 1960s. We observe a warming at the surface and a cooling above, which is consistent with the effect of added greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and inconsistent with the hypothesis of solar influence. Source: Met Office Hadley Centre.

In addition to this atmospheric “fingerprint”, incoming and outgoing radiation measurements from satellite observations provide another line of direct evidence linking atmospheric greenhouse gas content to global warming[10,11]. Such studies invalidate May’s statement that “the human influence on climate has never been observed or measured”.

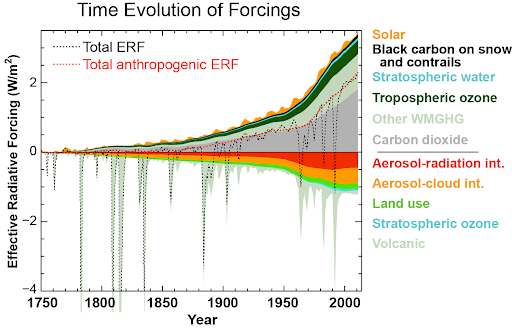

When assessing the influence of all possible climate forcing mechanisms in a comprehensive literature review, the Fourth National Climate Assessment of the U.S.[12] identified CO2 and other well-mixed greenhouse gases as the dominant drivers of modern warming whereas the influence of solar activity was shown to be extremely minor (Figure 3), a finding also supported by the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report[1] and, more recently, the Sixth Assessment Report[13].

Figure 3. Time evolution in effective radiative forcings (ERFs) across the industrial era for anthropogenic and natural forcing mechanisms. The ERF measures the net heat gain or loss in the Earth’s climate system. Well-mixed greenhouse gases (WMGHG) are the long-lived gases that have a strong impact on climate and include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and different kinds of chlorofluorocarbons. Source: U.S. Fourth National Climate Assessment.

May’s claim that climate models use “circular proof” in order to attribute warming to greenhouse gas emissions is rooted in the author’s misunderstanding of a value derived from climate models called transient climate response (TCR). TCR is the degree of model-simulated global warming associated with a 1% increase in CO2 per year compared to the preindustrial CO2 concentration[14]. Referencing Gillett et al., (2013)[14], May writes that previous IPCC models overestimated TCR and that the explicit assumption of the relationship between CO2 and warming in the definition of TCR is an example of “circular proof” when attributing the cause of warming to greenhouse gas emissions. However, TCR is not used in climate models to attribute warming to greenhouse gas emissions, but is rather a metric that scientists calculate to compare the performance of simulations from multiple climate models against each other and observations.

Gillett et al. (2013) used more recent model simulations and observational temperature data not available to IPCC authors at the time in order to calculate a new range of estimates for the transient climate response to cumulative carbon emissions (TCRE). Related to TCR, TCRE is defined as “the ratio of global-mean warming to cumulative emissions at CO2 doubling in a 1% [per year] CO2 increase experiment”.[14] The new estimates were found to be between 0.7 and 2.0 K per EgC (exagrams, or 1015 kg, of carbon).[14] By contrast, previous estimates derived from models were reported to be between 0.8 and 2.4 K per EgC. This indicates that the level of simulated global-mean warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions is different for each model.

The spread in TCR is due to different representations of the complex physical climate system and biogeochemical processes that models approximate. Thus, they shed light on the importance of accurately representing these processes in models.

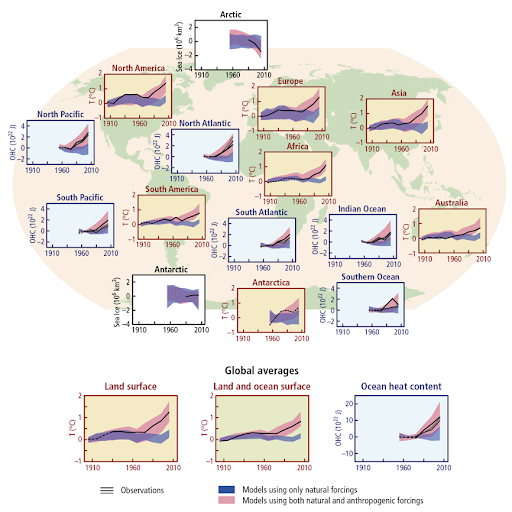

However, despite inter-model disagreements in TCR, the Climate Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) models questioned by May were previously shown to reliably reproduce observational trends in surface land temperature, surface ocean temperature and ocean heat content around the world when using both natural (e.g., the Sun) and anthropogenic (e.g greenhouse gas emissions) forcings since the beginning of the twentieth century, but not natural forcings alone (Figure 4).

The range of temperature and ocean heat content values simulated by the suite of CMIP5 models, of which observations generally fall close to the center, does not support May’s statement that models “clearly overestimate” warming. Similar claims about IPCC climate models have been previously reviewed by Climate Feedback and were found to be inaccurate. This is also consistent with more recent research that evaluated the performance of earlier CMIP models and found that “climate models published over the past five decades were skillful in predicting subsequent GMST [global mean surface temperature].”[15]

Figure 4. CMIP5 model simulations of land and ocean surface temperatures in addition to ocean heat content since the beginning of the twentieth century using natural and anthropogenic (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions) climate forcings (red) and natural (e.g., solar irradiance) forcings alone (blue). Black lines denote observations. Source: Working Group I, IPCC AR5

Scientists’ Feedback

Postdoctoral research associate, Princeton University

“The author’s conclusion of circular logic is based on their misunderstanding of the TCRE [Transient climate response to cumulative carbon emissions, defined as ‘the ratio of global-mean warming to cumulative emissions at CO2 doubling in a 1% [per year] CO2 increase experiment’[14]]. The definition of the TCRE is not itself ‘proof’ that CO2 emissions drive climate change; it is just a simple metric to summarize Earth’s climate sensitivity to CO2 emissions and to facilitate comparisons between models and observations.

The author is correct that detection and attribution methods, as used in the paper, indirectly use models to determine the spatial fingerprints of separate forcing components. It is ironic, however, that they consider these fairly rigorous and physical model-based methods to be disqualifying and yet in the next sentence celebrate Connolly et al’s (2021) ‘simple linear regression’ of surface temperature records against total solar irradiance [which is also a model] as ‘abundant evidence’ that the Sun drives climate change.

Worst of all, the author completely ignores the fact that even putting General Circulation Models [the type of state-of-the-art models used by the IPCC] aside completely, there is ‘abundant evidence’ of greenhouse gas-induced climate changes, perhaps most notably the spectrally-resolved measurements of incoming/outgoing radiative fluxes which clearly show the net effects of absorption and re-emission in greenhouse gas bands.[12,13]”

References

- 1 – IPCC (2013) Working Group I, IPCC AR5.

- 2 – Oreskes (2004) The scientific consensus on climate change. Science.

- 3 – Anderegg et al. (2010) Expert credibility in climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- 4 – Cook et al. (2013) Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters.

- 5 – Cook et al. (2016) Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters.

- 6 – Lockwood & Fröhlich (2007) Recent oppositely directed trends in solar climate forcings and the global mean surface air temperature. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences.

- 7 – Lockwood (2008) Recent changes in solar outputs and the global mean surface temperature. III. Analysis of contributions to global mean air surface temperature rise. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences.

- 8 – Santer et al. (2013) Human and natural influences on the changing thermal structure of the atmosphere. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- 9 – Hegerl & Wallace (2002) Influence of patterns of climate variability on the difference between satellite and surface temperature trends. Journal of Climate.

- 10 – Raval & Ramanathan (1989). Observational determination of the greenhouse effect. Nature.

- 11 – Schmidt et al. (2010). Attribution of the present-day total greenhouse effect. Journal of Geophysical Research.

- 12 – U.S. Fourth National Climate Assessment, Climate Science Special Report.

- 13 – IPCC (2021). Working Group I, IPCC AR6

- 14 – Gillett et al. (2013). Constraining the ratio of global warming to cumulative CO2 emissions using CMIP5 simulations. Journal of Climate.

- 15 – Hausfather et al. (2019). Evaluating the performance of past climate model projects. Geophysical Research Letters.