- Health

New Scientist article accurately summarises polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) research but overstates significance of animal studies

Reviewed content

Headline: "Cause of polycystic ovary syndrome discovered at last"

Published in New Scientist, by Alice Klein, on 2018-05-14.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

Published by New Scientist, this article reports the findings of a study by scientists at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. In this study, researchers investigated the disease called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which affects up to one-fifth of women worldwide. A common cause of infertility, PCOS can also lead to metabolic problems (e.g. obesity and diabetes) and hirsutism (excessive growth of body hair), causing health problems and emotional distress.

In this study, researchers found that pregnant women with PCOS had higher levels of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH). As PCOS often runs in families, this prompted them to see if excess AMH in mothers could cause PCOS in daughters. To do this, they injected AMH into pregnant mice, and then studied the female offspring. They found that these offspring showed many symptoms of PCOS (such as delays in becoming pregnant and fewer ovulations). This finding was attributed to AMH overstimulation of brain cells involved in testosterone production. Researchers then injected a drug called cetrorelix into these affected mice, and found that this treatment diminished PCOS symptoms. Based on these findings, the researchers have embarked on a clinical trial to treat PCOS using cetrorelix in humans.

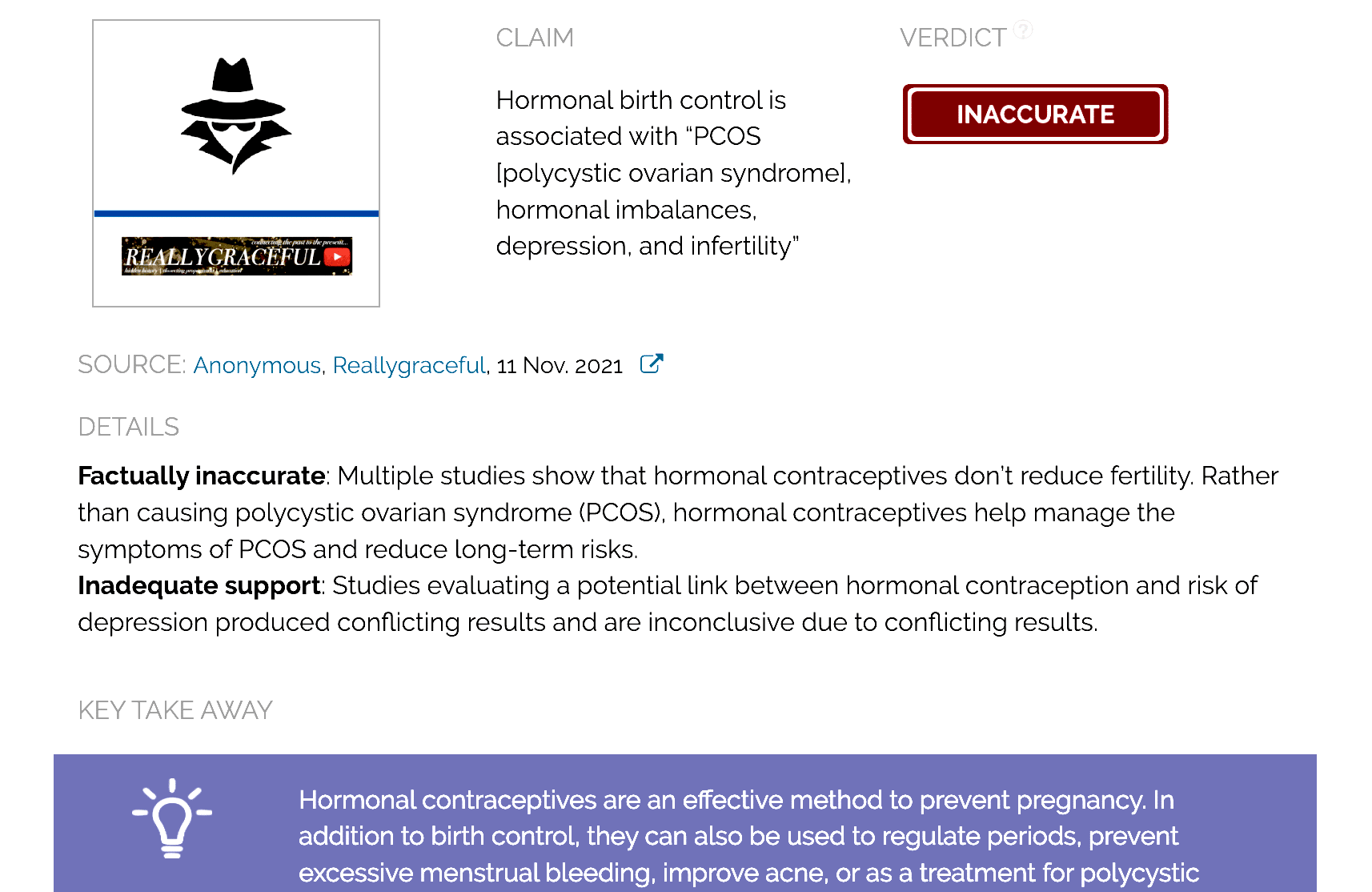

Clinicians who reviewed the article found that it reported the study’s findings accurately. However, they found the article’s headline to be highly misleading and to exaggerate scientific confidence by claiming that the cause of PCOS was found. Reviewers explained that the researchers’ findings were obtained from mouse models – and while promising and deserving of further investigation – findings from animal studies do not necessarily translate to what happens in humans with the same disease. Therefore, the article’s headline makes a highly premature claim. Reviewers cautioned that much more research is needed before the cause of PCOS in humans can be definitively linked to excess AMH.

You can read the original article here.

[This is part of a series of reviews of 2018’s most popular health and medicine stories on social media. This article has been shared more than 400,000 times.]

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK:

Professor (Reproductive and Periconceptual Medicine), University of Adelaide

Some of the facts are correct relating to the paper but the use of the word “cure” is misleading. Please note that although I am quoted in the New Scientist article, I have no role in the research that it reported.

Head of Research (Homerton Fertility Centre), Homerton University Hospital

This is, on the whole, an article that reflects the findings of the research published in Nature Medicine. A few points that did catch my critical eye: I think that the title overstates the position with the present level of knowledge and is too sensationalist. The ‘ovarian cysts’ stated to typically characterize PCOS are not cysts but follicles and this may be misleading. On the positive side, the quotes from Professor Robert Norman are spot on and accurately quoted (see Annotations below).

The clinical trial with cetrorelix which the scientists are about to perform will not work in my opinion, and stated here, may give false hope of an easy fix to many women. However, this is not the fault of Alice Klein who is merely quoting the original authors.

[A comment on the original research article in greater detail by Roy Homburg can be found here.]

Professor (Obstetrics & Gynaecology), University of New South Wales

This is the latest in a series of over-hyped reports claiming major new developments in human pathophysiology and therapeutics based on data from rodents. Our own research group works extensively on mouse models of PCOS, which are useful and well validated, but to claim that the “cause of PCOS has been discovered at last” on the basis of rodent data is misleading and will raise false hopes and cause distress to many women who suffer from this condition.

As we saw recently with reports of the “breakthrough” announcement that Vitamin B3 can prevent miscarriage[1], extremely high-quality and beautifully executed science performed in rodent research labs can be over-interpreted and prematurely translated into a clinical setting by popular science reporters and news media. These stories are widely circulated and believed unreservedly by the credulous. Later retractions of the hyped claims inevitably result in disillusionment and cynicism amongst the clinical research community and the public. Well designed and properly executed clinical trials must be performed to establish whether paradigms established in mouse models can be applied clinically.

The current report based on work by Giacobini and colleagues suggests that excessive fetal exposure to anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in mice may predispose to PCOS-like traits in female offspring. More surprisingly, using cetrorelix, which reduces levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), appeared to reverse this effect in mice. Conventionally, AMH appears in pre-antral and small antral follicles within the ovary. These stages of follicle development do not rely on FSH, so it is difficult to see how cetrorelix could affect an AMH-mediated pathway.

However, these medications are widely used in in vitro fertilization and do not appear to have effects on early embryonic development. Use in later pregnancy is less well-documented but will probably be harmless. Other approaches to suppress AMH synthesis and secretion could also be employed during pregnancy if this is indeed part of the cause of PCOS in humans.

A more fundamental problem with the authors’ hypothesis lies with the observation that female neonates do not have significant detectable concentrations of AMH in their blood. This suggests that AMH does not cross the placenta, at least later in pregnancy, making it unlikely that maternal circulating AMH is ‘seen’ by fetal tissues such as the ovary or brain. Again, further experimental data from human subjects could provide a more thorough picture of placental transfer earlier in pregnancy. But until such results are available, it seems premature to claim that we now know the “cause” of PCOS.

- 1 – Shi et al. (2017). NAD Deficiency, Congenital Malformations, and Niacin Supplementation. New England Journal of Medicine.

Professor (Department of Physiology and Pharmacology), Karolinska Institute

Overall, the summary reflects the content of the original article published in Nature Medicine. As commented by Prof. Rob Norman, the data support the hypothesis that excessive hormone secretion (e.g. elevated AMH or elevated androgen levels in the mother during pregnancy) may program the female offspring to develop a PCOS-like phenotype at adulthood. They also demonstrated that treatment aiming to act on the secretion of hormones from the brain could protect from developing PCOS-like symptoms. These data have to be interpreted with care.

Annotations

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

“It’s by far the most common hormonal condition affecting women of reproductive age but it hasn’t received a lot of attention,” says Robert Norman at the University of Adelaide in Australia.“

“If the syndrome is indeed passed from mothers to daughters via hormones in the womb, that could explain why it’s been so hard to pinpoint any genetic cause of the disorder, says Norman. “It’s something we’ve been stuck on for a long time,” he says.

“The findings may also explain why women with the syndrome seem to get pregnant more easily in their late 30s and early 40s, says Norman. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels are known to decline with age, usually signalling reduced fertility. But in women who start out with high levels, age-related declines may bring them into the normal fertility range – although this still needs to be tested, says Norman.”

Head of Research (Homerton Fertility Centre), Homerton University Hospital

On the positive side, these quotes from Professor Robert Norman are spot on and accurately quoted.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.