- Health

Marty Makary relies on misleading and unsubstantiated claims to accuse U.S. government of spreading misinformation

Key takeaway

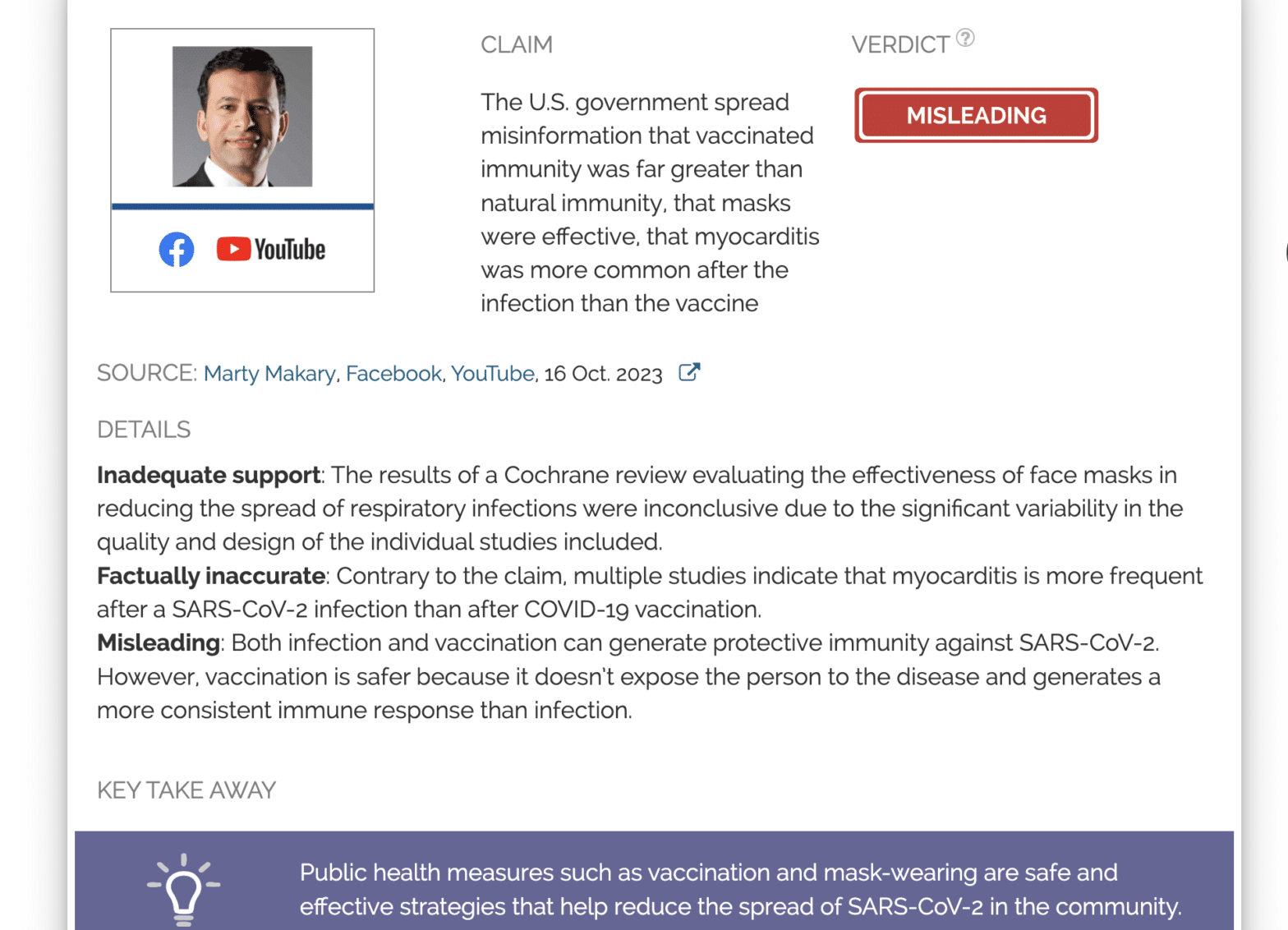

Public health measures such as vaccination and mask-wearing are safe and effective strategies that help reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the community. Because public health policies are evidence-based, they rely on the scientific evidence accumulated at a particular time. In the case of a novel pathogen about which little was known, this evidence was extremely scarce in the early stages. For this reason, public policies have evolved with time to align with new evidence that emerged later on.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

The U.S. government spread misinformation that vaccinated immunity was far greater than natural immunity, that masks were effective, that myocarditis was more common after the infection than the vaccine

Verdict detail

Inadequate support: The results of a Cochrane review evaluating the effectiveness of face masks in reducing the spread of respiratory infections were inconclusive due to the significant variability in the quality and design of the individual studies included.

Factually inaccurate: Contrary to the claim, multiple studies indicate that myocarditis is more frequent after a SARS-CoV-2 infection than after COVID-19 vaccination.

Misleading: Both infection and vaccination can generate protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2. However, vaccination is safer because it doesn’t expose the person to the disease and generates a more consistent immune response than infection.

Full Claim

“Greatest perpetrator of misinformation during the pandemic has been the United States government. Misinformation that COVID was spread through surface transmission. That vaccinated immunity was far greater than natural immunity. That masks were effective[...]That myocarditis was more common after the infection than the vaccine

Review

In October 2023, a video in which surgeon Marty Makary accused the U.S. government of being the “Greatest perpetrator of misinformation during the pandemic” circulated on Facebook.

This video showed an excerpt of a Roundtable “Examining COVID Policy Decisions”, led by the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic, held at the U.S. House of Representatives on 28 February 2023. The video had previously gone viral in March 2023, gathering millions of views and tens of thousands of interactions on social media and video platforms, including YouTube.

During his speech, Makary brought up several pieces of alleged misinformation spread by the U.S. government about SARS-CoV-2 transmission, “natural immunity”, the effectiveness of face masks, and the risk of myocarditis following vaccination.

This isn’t the first time that Makary criticized these and other supposed mistakes in the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as Health Feedback documented in earlier reviews.

Evaluating the effectiveness of past public health policies is essential to inform preparedness against future health threats. Likewise, the role of public health agencies in implementing and communicating these policies in a timely fashion is fundamental for public trust.

To be clear, there is credible debate and criticism of the COVID-19 response. For example, the lack of clear communication from authorities and the delays in incorporating new scientific evidence into policy-making were some of the weaknesses highlighted in the response.

But it’s important to distinguish between criticism that is grounded in evidence and misinformation in the guise of criticism. As we will explain below, Makary’s criticisms are unsupported by scientific evidence, misleading, and don’t take into account the fact that public health policy needs to evolve along with growing scientific knowledge about the virus.

Claim 1 (Misleading):

The government spread misinformation “That masks were effective”; “Now we have the definitive Cochrane review”

The claim that “masks don’t work” went viral in February 2022 based on a Cochrane review published on 30 January 2021[1]. The review evaluated whether physical interventions—including face masks, handwashing, and physical distancing—were effective at reducing the spread of respiratory viruses. To do that, the researchers analyzed data pooled from multiple randomized controlled trials that tested the effectiveness of these interventions.

The review concluded that “hand hygiene is likely to modestly reduce the burden of respiratory illness”. In contrast, the authors reported that “wearing a mask may make little to no difference” in the number of influenza and COVID-19 cases.

A viral opinion piece by journalist Bret Stephens for the New York Times, titled “Mask Mandates Did Nothing”, served as the springboard for many posts to present the Cochrane review as definitive evidence that “masks don’t work”. In it, Stephens quoted comments by the review’s first author, epidemiologist Tom Jefferson, during a Substack interview where he stated, “There is just no evidence that they make any difference. Full stop”.

But in a later opinion piece responding to Stephens’ article, Karla Soares-Weiser, the editor-in-chief of The Cochrane Library, told The Times that such claims misinterpreted the results of the Cochrane review. On the same day, the Cochrane Library released an official statement that went into greater detail on Soares-Weiser’s comment:

“Many commentators have claimed that a recently-updated Cochrane Review shows that ‘masks don’t work’, which is an inaccurate and misleading interpretation.

It would be accurate to say that the review examined whether interventions to promote mask wearing help to slow the spread of respiratory viruses, and that the results were inconclusive. Given the limitations in the primary evidence, the review is not able to address the question of whether mask-wearing itself reduces people’s risk of contracting or spreading respiratory viruses.

The review authors are clear on the limitations in the abstract: ‘The high risk of bias in the trials, variation in outcome measurement, and relatively low adherence with the interventions during the studies hampers drawing firm conclusions.’” [emphasis added]

Indeed, the claim that “masks don’t work” is unsupported by the review’s analysis and overlooks its limitations, which Health Feedback discussed at length in an earlier review.

Meta-analyses play a fundamental role in evaluating the effectiveness of health interventions. However, the reliability of their conclusions is directly proportional to the quality and similarity of the individual studies included in the analysis.

In this regard, the studies included in the Cochrane review varied greatly in terms of quality, study design, and outcomes observed. These studies were also highly heterogeneous, meaning that the studies were performed in very different ways. This makes it difficult to compare like with like. The type of mask tested across the studies was different, as was the respiratory virus whose transmission was studied. The study populations were also different, which affects their risk of exposure.

Further complicating the interpretation of the results, not all the participants in the individual trials wore face masks consistently. In addition, most trials only tested mask effectiveness at preventing infection in the wearer. This approach ignores the potential benefit of face masks in preventing an infected wearer from spreading the infection to others (source control), which is the primary purpose of face masks and accounts for a great part of their protection[2,3].

Due to all these limitations, which the Cochrane review acknowledged, the evidence was insufficient to draw reliable conclusions about whether face masks had an effect in the real world. Conducting randomized clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of mask-wearing involves many ethical and methodological issues, and the high heterogeneity of the studies included in the Cochrane review could have diluted any potential benefit of mask-wearing.

Laboratory studies show that face masks effectively block viral particles, particularly from the wearer[2,4]. Although determining the effect of face masks in community settings in the real world requires more research, several studies suggest they have a moderate effect, particularly when the circulation of the virus is high[5-7].

Claim 2 (Inaccurate):

Myocarditis is “four to 28 times more common after the vaccine” than after SARS-CoV-2 infection

mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are associated with an increased risk of myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), particularly in young males and after a second dose. However, such cases are rare, and most patients have only mild symptoms and recover quickly[8].

During his speech, Makary didn’t cite the source of the figure he mentioned or any other supporting data. We reached out to Makary for comment on the source of this figure and will update this review if new information becomes available.

In any event, Makary’s claim is directly contradicted by multiple studies showing that the risk of myocarditis and other heart problems is much higher after COVID-19 itself than after vaccination[9-12]. Furthermore, this risk might remain elevated for at least a year after the initial infection, even in people who only had mild disease[13].

Given the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing severe risks associated with COVID-19, professional medical associations, including the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, consider that the benefit-to-risk balance of COVID-19 vaccines is very favorable for all age and sex groups[14].

Claim 3 (Misleading):

The government spread misinformation that “vaccinated immunity was far greater than natural immunity”

This claim is misleading in multiple ways. First, public health authorities didn’t dispute the fact that infection can generate immunity. However, given the initial lack of knowledge about the virus and the immune response against infection, there was no evidence about how much and for how long a previous infection protected against future infection.

More recent research shows that infection-induced immunity can be long-lasting, in some cases even more than vaccine-induced immunity[15]. But regardless of its level and durability, infection-induced immunity comes at a price, which is exposing the person and those in contact with that person to the disease and its associated risks. For this reason, vaccination is the safest approach to achieve immunity because it avoids this exposure and its unpredictable consequences.

Second, the immune response after infection can vary greatly from person to person, depending on factors such as the severity of the disease and the circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants[16,17].

Paul Offit, a pediatrician and professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, explained to Health Feedback, “If your initial illness with COVID is an asymptomatic infection or a mildly symptomatic infection, you may be less protected than if you’re vaccinated”. This means that recovering from a SARS-CoV-2 infection doesn’t guarantee protection against future infections.

While vaccines aren’t 100% effective, they tend to provide more consistent protection compared to that from infection because the dose of vaccine a person receives is known to generate an effective immune response based on data from clinical trials.

Finally, the discussion about which type of immunity is better is a false dilemma that incorrectly presents infection and vaccination as mutually exclusive options when they aren’t. In fact, there is ample evidence that previously infected individuals also benefit from vaccination. Several robust studies show that hybrid immunity—the combined immunity resulting from infection and vaccination—lasts longer and provides better protection than infection- or vaccination-induced immunity alone[15,18,19].

Claim 4 (Lacks context):

The government spread “Misinformation that COVID was spread through surface transmission”

Evaluating past policies without acknowledging that scientific knowledge evolves and becomes more extensive with time can be misleading.

In the early days of the pandemic, the lack of knowledge about a novel virus forced public health authorities to make decisions with a high degree of uncertainty. Based on the research regarding known respiratory viruses at that time, public health authorities assumed that SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurred mainly through respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces.

Later research showed, however, that the risk of transmission through contaminated surfaces was low compared to the main routes of transmission—respiratory droplets and aerosols. Respiratory droplets are particles ranging from five to ten micrometers in size that are released when a person coughs, sneezes, speaks, or breathes. Aerosols are particles smaller than five micrometers that, in contrast to respiratory droplets which fall to the ground quickly, can remain in the air for a longer time and travel further distances.

But the fact that contaminated surfaces aren’t a major route of transmission doesn’t mean that they don’t play any role in infection, as Makary suggested. In studying the risk of transmission, how much contaminated surfaces contribute to that risk is difficult to disentangle from respiratory transmission. However, some early studies provided evidence compatible with people getting infected by touching contaminated surfaces[20,21].

More recently, a study published in The Lancet Microbe in April 2023 reported for the first time a correlation between the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles and viral RNA on frequently touched surfaces and the risk of infection in 279 households in London[22]. Although the authors couldn’t rule out aerosol transmission occurring in parallel, their results strongly suggested that viral contamination on people’s hands contributed significantly to SARS-CoV-2 transmission within the households.

Even if surface transmission only contributes to a small number of infections, these studies highlight the importance of handwashing as a simple preventive measure, which has been associated with a reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection[23].

Conclusion

Overall, Makary’s narrative conveyed the message that the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic wasn’t informed by evidence. However, this is based on statements that are unsupported or even contradicted by scientific evidence. While evaluating past public health policies can help improve the response to future health threats, one needs to take into account that policy-making can be challenging when scientific data is scarce and that policies developed in such circumstances can evolve as new evidence becomes available.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Jefferson et al. (2023) Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews.

- 2 – Mello et al. (2022) Effectiveness of face masks in blocking the transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A preliminary evaluation of masks used by SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. Plos ONE.

- 3 –Brooks and Butler (2021). Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA

- 4 – Pan et al. (2021). Inward and outward effectiveness of cloth masks, a surgical mask, and a face shield. Aerosol Science and Technology.

- 5 – Abaluck et al. (2022) Impact of community masking on COVID-19: A cluster-randomized trial in Bangladesh. Science.

- 6 – Riley et al. (2022) Mask Effectiveness for Preventing Secondary Cases of COVID-19, Johnson County, Iowa, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- 7 – Cowger et al. (2022) Lifting Universal Masking in Schools – Covid-19 Incidence among Students and Staff. New England Journal of Medicine.

- 8 – Heymans and Cooper (2022) Myocarditis Following SARS-CoV2 mRNA Vaccination Against COVID-19: Facts and Open Questions. Nature Reviews Cardiology.

- 9 – Barda et al. (2021) Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. New England Journal of Medicine.

- 10 – Patone et al. (2022) Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation.

- 11 – Voleti et al. (2022) Myocarditis in SARS-CoV-2 infection vs. COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Research.

- 12 – Block et al. (2022) Cardiac Complications After SARS-CoV-2 Infection and mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination — PCORnet, United States, January 2021–January 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

- 13 – Xie et al. (2022) Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine.

- 14 – Writing Committee. (2022) 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: Myocarditis and Other Myocardial Involvement, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, and Return to Play: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

- 15 – Bobrovitz et al. (2023) Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: a systematic review and meta-regression. The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

- 16 – Tomic et al- (2022) Divergent trajectories of antiviral memory after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Communications.

- 17 – COVID-19 forecasting team (2022) Variation in the COVID-19 infection–fatality ratio by age, time, and geography during the pre-vaccine era: a systematic analysis. The Lancet.

- 18 – Malato et al. (2023) Stability of hybrid versus vaccine immunity against BA.5 infection over 8 months. The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

- 19 – Stamatatos et al. (2021) mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science.

- 20 – Bae et al. (2020) Asymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on Evacuation Flight. Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- 21 – Xie et al. (2020) The evidence of indirect transmission of SARS-CoV-2 reported in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health.

- 22 – Derqui et al. (2023) Risk factors and vectors for SARS-CoV-2 household transmission: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Microbe.

- 23 – Beale et al. (2020) Hand Hygiene Practices and the Risk of Human Coronavirus Infections in a UK Community Cohort. Wellcome Open Research.