- Climate

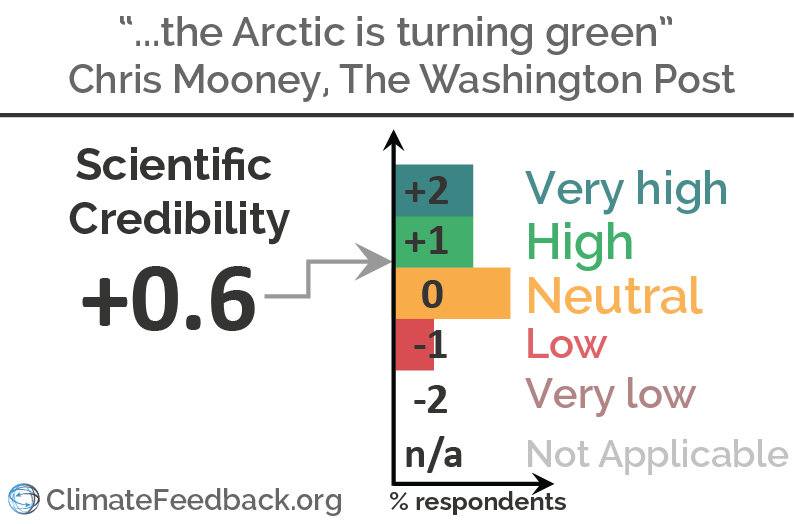

Analysis of "Thanks to climate change, the Arctic is turning green"

Reviewed content

Published in The Washington Post, by Chris Mooney, on 2016-06-27.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

Overall the article accurately reports that increased temperatures and atmospheric CO2, due to human greenhouse gas emissions, are already increasing plant growth in the Arctic region. However, scientists point to some misleading aspects of the article: most problematically, the author leaves open the hypothesis that the increased CO2 uptake by plants in the Arctic could significantly offset future global warming. In reality, scientists already take into account CO2 uptake by plants in climate projections and conclude that Arctic greening is very unlikely to have a significant impact on the global carbon cycle.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

PhD candidate, Eawag, The Swiss Federal Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology

The main message of this article – that the Arctic is greening, and that this trend is caused by anthropogenic climate change – is accurate and well-explained. The author also addresses the complexity of the trend’s potential impacts on the Arctic itself and on global greenhouse gas concentrations.

Regents Professor, University of Minnesota

The article is a poster child for a lot of what is wrong with even our “hypothetically” best mainstream press coverage of science and the environment. The article is factually accurate (up to a point) but incomplete. It is true that rising CO2 and longer growing seasons likely will increase LAI [leaf area index] and productivity in certain northern regions, but the article gives the impression (by intentionally or unintentionally conflating northern regions and the rest of the world) that this may be widespread. Additionally, and equally or more problematically, the article is imbalanced in not fully acknowledging that the scale of net positive impacts (in terms of increased carbon gain) in far northern regions will likely only partially offset:

- carbon losses from high latitude ecosystems (e.g. soil carbon losses from peatlands and permafrost due to decomposition, respiration and/or fire),

- climate-change induced losses of productivity in the tropics, and

- climate-change induced losses of carbon from increased wildfires in southern boreal and temperate coniferous forests.

Thus the article fails my “objectivity” test in being more about making a news splash than about reporting these important findings accurately framed within the overall broader context.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

Overall, this is an excellent article. It not only reports the key scientific findings but also highlights several key uncertainties. This article nicely balances a description of what we think we know with a description of what we know we don’t know. Overall, I would consider this an exemplary piece of science journalism.

My one critique would be the assumption implicit in the reporting that greening is all good. While greening is good for some things, greening can be disruptive to ecosystems. Organisms that were well-adapted to harsher conditions might find themselves at an ecological disadvantage as conditions ameliorate, and thus there will be winners and losers. Thus greening can have adverse consequences for biodiversity.

This implicit assumption that greening is good is reflected in the title of the piece, raising the issue of who or what we should ‘thank’ for the greening.

Overall, however, this is a thoughtful and nuanced piece of scientific reporting.

Program Manager, US Geological Survey

Overall a nice description of the state of the science; well-referenced and linked; outlines the uncertainties; describes how this work builds on, but is different from, prior work.

Research Associate, Harvard University

This article reports on a new high-profile study that formally attributes the documented greening of the Arctic to human greenhouse gas emissions. The article correctly places this new research in its context (the greening had been observed before, but not explained) and identifies what is new in the study.

However, the author then goes on to discuss the implications of this greening for the carbon cycle, and somehow implies that these results about Arctic greening are new cause for optimism, as greening will be associated with CO2 absorption by the land which will slow down global warming. This whole discussion, in my view, was confused and potentially misleading for readers. The distinction between “greening” and ecosystems being a potential sink/source of carbon is not well presented. Arctic greening is well documented, but whether this means the Arctic is storing more and more carbon (and will keep doing so in the future) is unclear, and a topic of ongoing research. The article also seems to imply that these results are new cause for optimism because the land carbon uptake was somehow not accounted for in climate projections. This is incorrect. It is already well established that the land takes up about 25% of our CO2 emissions. Observations of greening at high latitudes are consistent with our expectations. The land carbon sink is already accounted for in climate change projections. There are some uncertainties, but the issue is mostly whether this sink will persist or decrease – not, as the author implies here, whether it will somehow go up to offset the entirety of human CO2 emissions and associated global warming.

The article reports about recent evidence that terrestrial ecosystems are ‘greening’ in response to human activities, principally the increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration. The author presents this ‘greening’ as a new finding while annual global carbon budgets have reported that about 25% of the fossil-fuel emissions have been taken up by the biosphere since the 1960s. Nothing is fundamentally wrong in the article but it is organized in a somewhat misleading way, with a high risk that the title could be taken out of context by “skeptics”.

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

This is a very nice article that lays out the recent evidence. It discusses the pluses and minuses of the issue and comes to a balanced conclusion.

The article is quite neutral and balanced. It describes the Arctic greening and its attribution to climate change and CO2 increase, also mentioning uncertainties. The article concludes by saying that “researchers do not seem to be arguing that it’s enough to counterbalance the entire human-induced warming trend”. On the contrary, this should be seen as evidence that “we are causing the Earth to change”.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from Chris Mooney; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Earlier this month, NASA scientists provided a visualization of a startling climate change trend — the Earth is getting greener, as viewed from space, especially in its rapidly warming northern regions. And this is presumably occurring as more carbon dioxide in the air, along with warmer temperatures and longer growing seasons, makes plants very, very happy.”

Regents Professor, University of Minnesota

The point in the second sentence may be true for areas where longer growing seasons and warmer temperatures do increase productivity, but it is likely false for vast other regions of the world where lack of moisture will outweigh positive impacts of global change on growth. So this sentence right off the bat gives a bit of a misrepresentation by being worded in a way that can be construed as applying globally not just in the far north. Also there is nothing “startling” about this trend – it is exactly as hypothesized for such regions.

“This is happening even as the overall warming of the planet may, by lengthening growing seasons and moistening the atmosphere, further stoke plant growth.”

Research Associate, Harvard University

… note that relative humidity over land, near the surface, is projected to decrease with global warming (i.e., humidity increases more slowly than temperature over land). This has been observed in the past 10-15 years (although the role of variability is still unclear). So “moistening of the atmosphere”, as far as vegetation is concerned, is not accurate (at least globally).

See: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/2013-state-climate-humidity

“The key question then becomes how much this process can offset overall global warming over time. And that’s quite unclear. “

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

Exactly. While the “greening” via extra plant growth could help put a brake on climate change, it depends on plants having enough water, and temperatures they thrive in. Neither of these are guaranteed in future, and the greening could easily become browning as the years pass. The overall effect on atmospheric concentrations of CO2 is likely to be small.

“He said he is not sure to what extent the greening trend will continue, as “disturbances” like wildfires might counteract it, or plants may become “acclimated to this kind of high temperature””

The Duke FACE [free-air CO2 enrichment] experiment also showed that it is not clear whether nutrient availability will continue supporting high rates of plant productivity despite higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

“It is clear, then, that greening is emerging as a factor with the potential to blunt some of the worst impacts of human greenhouse gas emissions.”

PhD candidate, Eawag, The Swiss Federal Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology

In fact, experts agree that the greening of the arctic is unlikely to even offset the increased carbon release from the arctic itself (much less the rest of the world) in a changing climate, for instance by permafrost melting:

The figure above is from a 2016 study that was authored by 100 expert researchers in various fields of arctic climate research, which concludes: “Our study highlights that Arctic and boreal biomass should not be counted on to offset permafrost carbon release and suggests that the permafrost region will become a carbon source to the atmosphere by 2100 regardless of warming scenario.”

“Still, the trend is already prompting more optimistic assessments of our climate future in some quarters. Arctic greening was recently cited, in a major report by the U.S. Geological Survey, as the central reason that the state of Alaska, despite worsening wildfires and more thaw of permafrost, might still be able to stow away more carbon than it loses over the course of the 21st century.”

Research Associate, Harvard University

a) This is highly uncertain, because, as discussed, the future of the greening trend is unclear b) it is only for Alaska, and is unlikely to make a significant difference for “our climate future” as the author mentions. c) even if it could be generalized to the entire Arctic, or the entire land, it is no cause for “optimism”: as discussed above, the land is already a carbon sink. It might remain one in the future, despite climate change, but the risk is actually that it decreases and leaves us with more of our emissions accumulating in the atmosphere.

“climate change skeptics and contrarians … have long contended that global warming won’t be all bad, and that plants might help offset any global warming trend.”

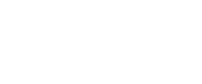

It is not only a skeptic’s argument: the land biosphere does offset part of the warming by taking up 25% of emissions. However, the uncertainty in the durability of this pattern is very large with no clear consensus between earth system models used in the IPCC latest assessment report, see Figure below:

From Friedlingstein et al (2014) Uncertainties in CMIP5 Climate Projections due to Carbon Cycle Feedbacks, Journal of Climate

“But thus far, researchers do not seem to be arguing that it’s enough to counterbalance the entire human-induced warming trend.”

Research Associate, Harvard University

Of course not. This sentence is highly misleading. As indicated above, the land carbon sink is a well-established phenomenon, not a new theory based on new observations related to Arctic greening and that somehow scientists would now be debating to know whether it will offset global warming entirely. Nobody is even talking about that. The issue is whether the current carbon sink (25% of our emissions) will maintain itself or decrease.

The “land sink” offsets about 25% of fossil-fuel emissions annually*. The long-term durability of the sink is debatable as it may be threatened by simultaneous enhancements of soil respiration due to warmer temperatures and more substrate availability (permafrost thaw in particular) but with a large climate-driven variability.

*data source: www.globalcarbonproject.org

Jacqueline Mohan, Associate Professor, University of Georgia

In terms of ecosystems being a carbon sink/storage or source to the atmosphere, it is essential we consider soils and soil microbes. The majority of Arctic ecosystem carbon is stored in the SOILS. With enhanced plant productivity, there is more “microbial food” in the form of organic carbon from plants going to the soils. More microbial food means more microbial metabolism/decomposition of organic carbon to CO2, which is an important SOURCE of carbon (CO2) to the atmosphere with a climate warming effect. To understand what is going on with Arctic ecosystem-climate interactions, we need to know what is going on with ecosystem respiration (C source to atmosphere) not just productivity (C sink from the atmosphere and the topic of the article on increasing “greeness”). In ecosystem ecology there is a finding of a “priming” effect on soil microbial C decomposition, where a small amount of yummy, labile C (the new green stuff coming from plants) can stimulate the decomposition and release to the atmosphere of very old, less yummy recalcitrant forms of C that had been stored in soils for a long time. This could actually result in more carbon being released to the atmosphere by Arctic ecosystems than they took from the atmosphere to support the measured enhancement in greenness.

“new research in Nature Climate Change not only reinforces the reality of this trend — which is already provoking debate about the overall climate consequences of a warming Arctic — but statistically attributes it to human causes, which largely means greenhouse gas emissions (albeit with a mix of other elements as well).”

Research Associate, Harvard University

That’s a good summary of what’s new in this study: Arctic greening had been documented before, its causes had been discussed, but this is the first study to formally attribute this greening trend to human gas emissions. Note that trends in surface temperature and in some aspects of the hydrological cycle (e.g., precipitation, evaporation) have been detected and attributed similarly; this is the first study to do so with vegetation trends (which appear closely related to temperature trends, though).

PhD candidate, Eawag, The Swiss Federal Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology

While the NASA project is a wonderful visualization with impressive details and scale, the trend of Arctic greening is not startling to scientists. Researchers have been studying the increase in plant growth in the arctic for well over two decades at this point. The author notes this later in his article, but framing the pattern as surprising for the lede is somewhat disingenuous. Whether the trend is slowing or reversing itself, why some areas are browning rather than greening, or what the long-term consequences might be are still very much debated, but the pattern itself is extremely well-established.

Here is some of the previous work detailing the trend:

- “Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes from 1981 to 1991” R. B. Myeni et al,

- “Greening of arctic Alaska, 1981-2001” Gensuo Jia et al

- “Vegetation greening in the canadian arctic related to decadal warming“, by the same authors also using satellite data, this time from 1982-2006

- “Divergent Arctic-Boreal Vegetation Changes between North America and Eurasia over the Past 30 Years“, Jian Bi et al, showing greening also in the European and Russian Arctic