- Climate

Human activities have dramatically increased atmospheric CO2 levels, causing imbalances in the global carbon cycle

Key takeaway

Atmospheric CO2 has increased rapidly as a result of human activities. Although human-caused emissions of CO2 are small relative to natural flows into and out of the atmosphere, the human contribution has caused an imbalance in the global carbon cycle that jeopardizes land and ocean ecosystems.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

Human additions of CO<sub>2</sub> are in the margin of error of current measurements and the gradual increase in CO<sub>2</sub> is mainly from oceans degassing as the planet slowly emerges from the last ice age.

Verdict detail

Factually inaccurate: Human activities have increased atmospheric CO2 levels from 280 ppm to more than 400 ppm since industrialization, which is an increase greater than the margin of error of current measurements. Oceans presently serve as a sink for CO2, not a source.

Misleading: Humans have caused an unprecedented rise in atmospheric CO2 levels in the last 800,000 years. This is because the natural flows in the global carbon cycle were previously in balance.

Full Claim

Human additions of CO<sub>2</sub> are in the margin of error of current measurements and the gradual increase in CO<sub>2</sub> is mainly from oceans degassing as the planet slowly emerges from the last ice age.

Summary

The claim appeared in multiple outlets, including Watts Up With That, the Daily Signal, and a Facebook post published by I Love Carbon Dioxide in April 2020. While human additions of CO2 are small relative to natural processes, atmospheric CO2 measurements are currently much higher than pre-industrialization CO2 levels and not within the “margin of error of current estimates,” as described by the reviewers below[1,2]. The ocean does release CO2, but scientific evidence demonstrates that oceans have absorbed approximately 23% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions since the Industrial Revolution, thus serving as a net sink rather than a source of CO2[3,4]. This claim also fails to recognize that human-induced CO2 emissions have caused imbalances in the global carbon cycle.

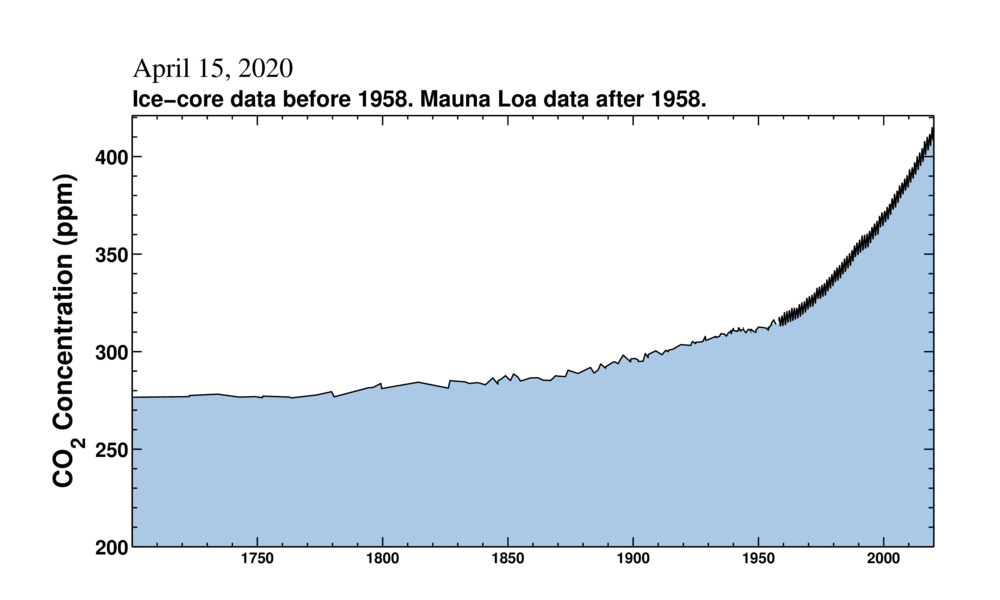

Pre-industrialization atmospheric CO2 levels were around 280 parts per million (ppm)[2]. Since 1950, the burning of fossil fuels, agricultural development, and other human-caused land-use changes have led to steady increases in atmospheric CO2. According to the IPCC, “This has led to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide that are unprecedented over at least the last 800,000 years.”[1,2] Today, atmospheric CO2 exceeds 400 ppm, as shown in the figure below.

Figure—The Keeling Curve, a daily record of global atmospheric CO2, shows relatively stable CO2 concentrations from 1700 to 1950, as measured by ice-cores. After 1950, CO2 concentrations rose rapidly from 300 to over 400 ppm, as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory. From Scripps Institute of Oceanography.

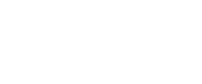

Pre-industrialization atmospheric CO2 levels remained relatively constant because the global carbon cycle was balanced. In other words, the amount of CO2 being released into the atmosphere from natural sources, such as the ocean and respiring organisms, was balanced by the amount of CO2 absorbed from the atmosphere. Human-caused increases in CO2 emissions have created an imbalance in the global carbon cycle, where more CO2 is being released than can be absorbed by natural carbon sinks (see figure below). Excess CO2 in the atmosphere warms the planet and excess CO2 in the oceans causes acidification that jeopardizes marine ecosystems[1,2,5].

Figure—The global carbon cycle from 2009 to 2018 shows that human contributions to atmospheric CO2 outweigh the amount of carbon cycled each year, leading to an annual budget imbalance of 2 GtCO2. From The Global Carbon Budget 2019.

Scientists’ Feedback

First of all, the claim that current changes in atmospheric CO2 are within the uncertainty of measurements is absurd. Since pre-industrial times atmospheric CO2 levels increased from roughly 280 ppm to now roughly 412 ppm (globally on January 2020) with growth rates currently exceeding 2 ppm/yr. These atmospheric CO2 (as well as other trace gas) measurements are highly accurate with errors estimated at 0.07 ppm[6].

Secondly, the claim that the increase results as “the Planet emerges from the last ice age” is wrong for multiple reasons. Firstly, ice-core atmospheric CO2 records suggest that such a strong increase (from 280ppm to 412 ppm) is unprecedented in the last 800,000 years. Secondly, these records also show that the speed at which atmospheric CO2 increases is unprecedented in the ice-core record history.

Finally, the ocean degassing CO2 is causing this “gentle and welcome” increase is fundamentally wrong and not supported by observations. While the anthropogenic perturbation might be small compared to the large natural carbon fluxes in the ocean , they are well detectable from measurements[1,2]. Current science suggests that the ocean is taking up (NOT releasing) roughly 2.5 PgC/yr of carbon from the atmosphere which corresponds to roughly 23% of annual human CO2 emissions[3,6]. This is supported by observation-based estimates using the partial pressure of CO2 collected in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas, repeat hydrography measurements of the dissolved inorganic carbon content, and estimates based on atmospheric inversions[1,4]. In summary, there are multiple, independent measurement-based flux estimates that highlight that the ocean is a significant net CO2 sink.

[Comment from a previous evaluation of a similar claim.]

Global human emissions are indeed only a small percentage of what ecosystems cycle, but the reasoning is completely flawed. Regarding the impact on climate, it is the net emissions that matter, not the amount of carbon that is being cycled over and over. Terrestrial ecosystems take up and re-emit about 12 times more CO2 than humans emit, and oceans cycle about 9 times more CO2 than we emit. BUT! This carbon uptake and release is more or less balanced at the annual scale, and net ecosystem emissions are even negative. Without these ecosystems, atmospheric CO2 concentration would have risen even more as a consequence of fossil fuel burning; the CO2 concentration in the air would already be around 550 ppm (instead of the current ~400 ppm). Hence, it is absolutely misleading to compare amounts of CO2 cycling through the ecosystems with human CO2 emissions in this context. If anything, the CO2 cycling through the ecosystems should be taken as a reason to safeguard them: if we lose these carbon sinks, CO2 in the air will increase no matter what we do.

REFERENCES

- 1 – IPCC (2007) Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- 2 – IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- 3 – Gruber et al (2019) The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science.

- 4 – Friedlingstein et al (2019) Global carbon budget 2019. Earth System Science Data.

- 5 – Doney et al (2009) Ocean acidification: The other CO2 problem. Annual Review of Marine Science.

- 6 – Zhao et al (2006) Estimating uncertainty of the WMO mole fraction scale for carbon dioxide in air. Journal of Geophysical Research.