- Climate

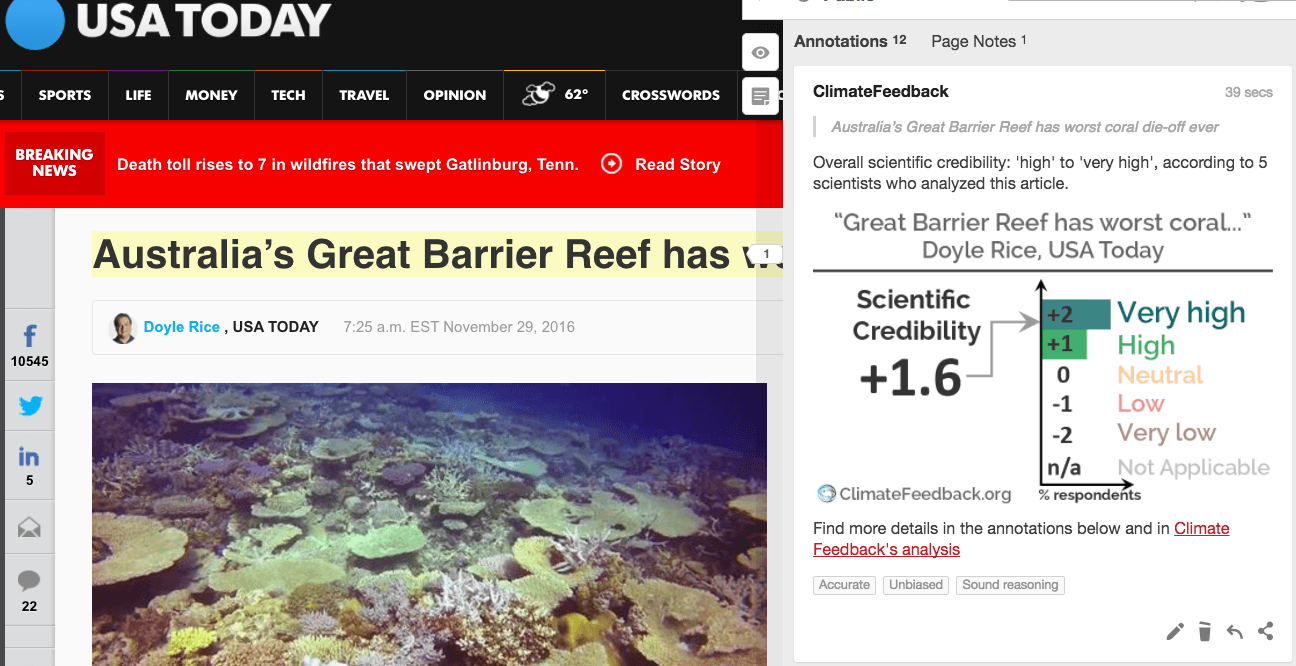

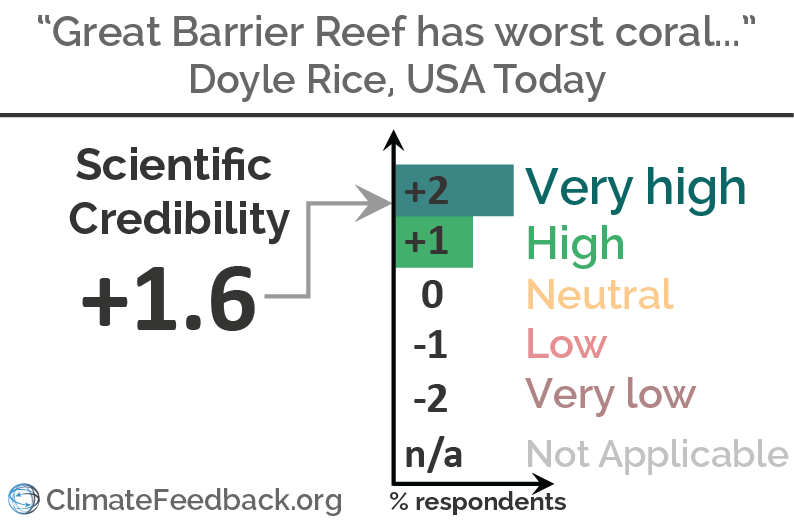

Analysis of "Australia’s Great Barrier Reef has worst coral die-off ever"

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

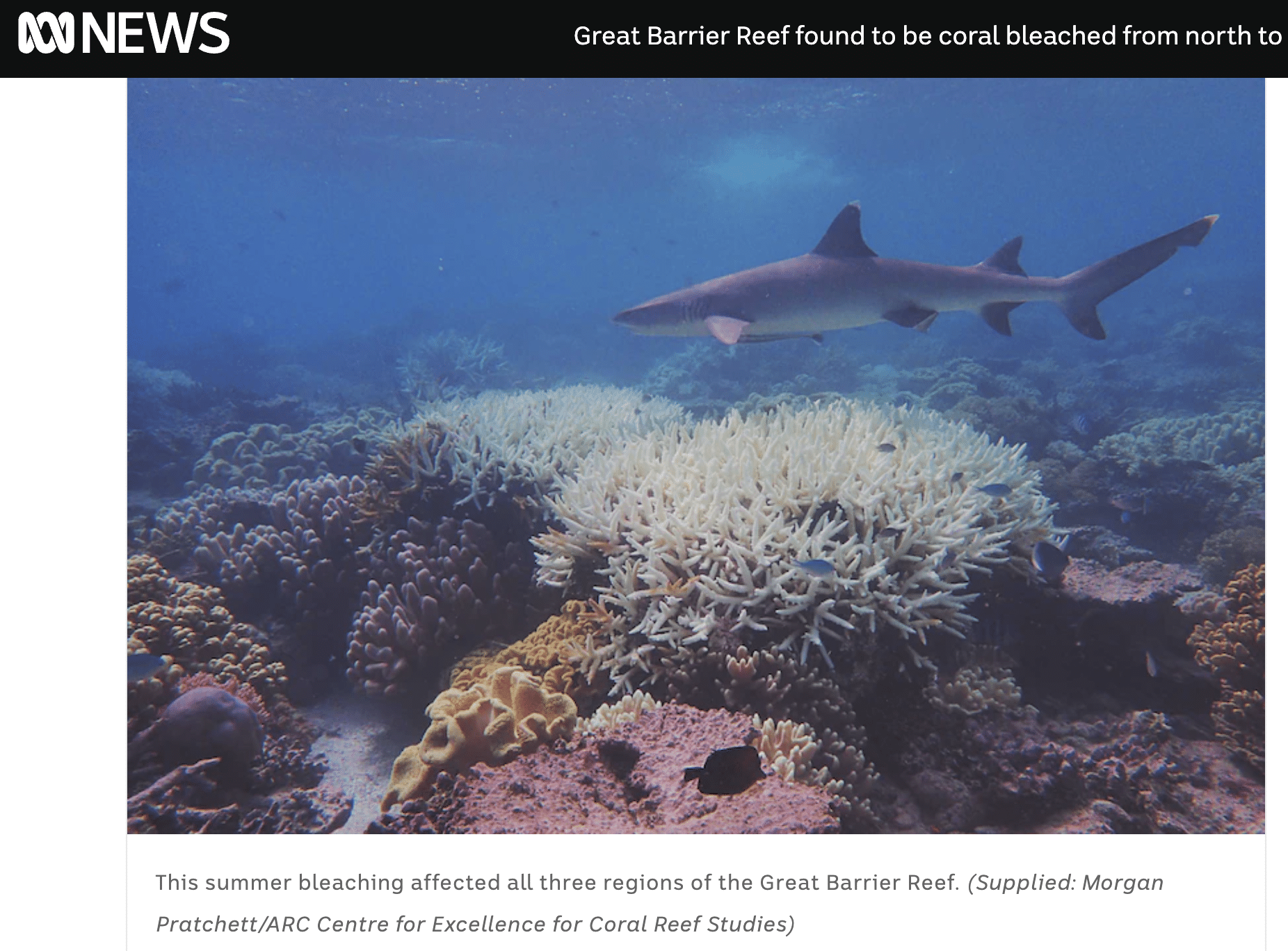

This article in USA Today reports on the latest survey of mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef released by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. This year, the northern portion of the reef has seen the worst bleaching ever observed with two-thirds of coral dead on average—even more in some locations. Southern sections of the reef experienced much less bleaching and death because of slightly cooler water.

The article correctly notes that climate change is making this kind of mass bleaching event more frequent, putting tropical reefs at risk. Reefs are ecosystems incredibly rich in biodiversity, and they provide economic value through tourism, fishing, and protection against coastal erosion.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

In general, the article got this one almost completely right, with one of my two quibbles being in one of the experts’ quotes. It is unfortunate, however, that the article didn’t put this story in the context of the global coral bleaching event that is still underway—currently hitting hardest in Micronesia and the Marshall Islands.

Professor, University of New South Wales

This article is mostly accurate. The author made one overstatement (that we will see yearly massive bleaching events at the Great Barrier Reef within the next decade). It should be noted, though, that the frequency of massive bleaching events is increasing, will continue to increase in the near future, and that these events do not need to occur annually to kill the reef. The variability of El Niño Southern Oscillation on top of the background warming trend of surface temperatures means that we will exceed the bleaching thresholds more frequently. In the future, the reefs won’t have time to recover between these events.

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

This is a very good article highlighting one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots and the grave risks it faces. One of two of the comments and ideas are off the mark, but it is largely factually correct.

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

Coral bleaching is a visual reminder of the influence of climate change on the world’s oceans and ecosystems. The article presents findings that support a massive bleaching event this year and some of the ecological and economic consequences of coral bleaching. Although lacking in key scientific references to support claims, the article is insightful and unbiased.

Professor, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

I concur with my colleagues that this is mostly an accurate article. A few points are exaggerated, as we all noted in the annotated version. And to be clear, this may well be the worse die off on the Great Barrier Reef, but we’ve been seeing die offs of this magnitude and geographic scope around the world for decades.

For example, coral reefs across the Caribbean experienced a die off of similar-to-larger scope 35 years ago. My entire career, I’ve been studying “post mass-coral die off” reefs in Jamaica, Belize, Cuba, etc. So in this regard, the event isn’t especially notable. The real lesson of the GBR coral mortality of 2016 isn’t that ocean warming is causing mass-coral die offs – we’ve known that for a quarter century. It is that even the world’s most remote, well-managed, and otherwise pristine reefs are susceptible.

Many of my colleagues have assumed and argued that ocean warming only causes mass coral mortality in the presence of other insults to the reef. Stressors like overfishing, pollution, tourism, etc. that were believed to weaken “natural resilience” to ocean warming. I co-authored a paper earlier this year* that found that reef isolation had no effect on coral loss – the world’s most isolated reefs, free from local human impacts, were just as degraded in terms of the amount of remaining living coral as reefs adjacent to large population centers. The bottom line is that no form of local management can save reefs from carbon emissions.

- Bruno and Valdivia (2016) Coral reef degradation is not correlated with local human population density, Nature scientific reports.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from Doyle Rice; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Scientists confirm a mass bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef this year has killed more corals than ever before, with more than two thirds destroyed across large swathes of the biodiverse site.”

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Actually, this is an underestimate as the “25% of the worst affected reefs (the top quartile), losses of corals ranged from 83-99%.”

“When water temperatures become too high, coral becomes stressed and expels the algae, which leave the coral a bleached white color.”

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The article should have noted that, while injured and starving, bleached corals are still alive. When thermal stress is severe or prolonged, corals often die. Thermally-stressed corals also frequently die due to disease outbreaks.

- NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program Infographic Gallery

- Burge et al (2014) Climate Change Influences on Marine Infectious Diseases: Implications for Management and Society, Annual Review of Marine Science

“The good news, scientists said, was that central and southern sections of the reef fared far better, with “only” 6% and 1% of the coral dead, respectively.”

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The pattern of warming this year resulted in the highest thermal stress being located in the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef. This can be seen in the coral bleaching products from NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch.

Source: NOAA Coral Reef Watch

“Stress from unusually warm ocean water heated by man-made climate change and the natural El Niño climate pattern caused the die-off.”

Professor, The University of Arizona

Yes, human-caused warming boosts the background temperature, so that warming associated with El Niño can now reach levels intolerable by corals.

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Roughly speaking, the El Niño may have added a quarter of a degree C to the global average in 2015/16, while the greenhouse-gas-related warming trend has added twice that much to the average values since the 1980s.

It’s also important to note that this is only one part of a global coral bleaching event that has been occurring since mid-2014.

“Mass coral bleaching is a new phenomenon and was never observed before the 1980s as global warming ramped up.”

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Correct.

- Baker et al (2008) Climate change and coral reef bleaching: An ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science

Professor, The University of Arizona

On the Great Barrier Reef, I believe this is true. Global (especially tropical) temperatures took a jump upwards in the late 1970s, providing the extra warmth that puts corals in danger.

“[…]looking to the future, mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef will likely be an annual phenomenon within a decade, Torda said.”

Scientist, Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

This may turn out to be true but most studies place annual bleaching, especially on the Great Barrier Reef, a bit further out—perhaps 2050.

- van Hooidonk et al (2013) Temporary refugia for coral reefs in a warming world, Nature Climate Change

Professor, University of New South Wales

This sentence is an overstatement. See, for example, Meissner et al. (2012)*: “By year 2030, 66–85% of the reef locations considered in this study would experience severe bleaching events at least once every 10 years. Regardless of the concentration pathway, virtually every reef considered in this study (>97%) would experience severe thermal stress by year 2050.” Having said that, mass coral bleaching events do not need to be an annual phenomenon to kill the reef. Coral reefs need years to recover from extreme bleaching events, which means that even a decadal occurrence of severe bleaching will not give the reef enough time to ever recover. While this sentence is an overstatement, the impact on the reef is the same.