- Health

Flawed “study” incorrectly claims that countries adopting hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 experienced reduced mortality rates

Key takeaway

Some governments have favored the use of hydroxychloroquine for treating or preventing COVID-19. However, this does not necessarily imply that the people within those countries used the drug more often than did people in countries that restricted hydroxychloroquine use. Therefore, correlating countries’ mortality rates with their stance towards hydroxychloroquine use results in a spurious association that is based on flawed reasoning. In contrast, growing evidence from large randomized clinical trials suggests no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

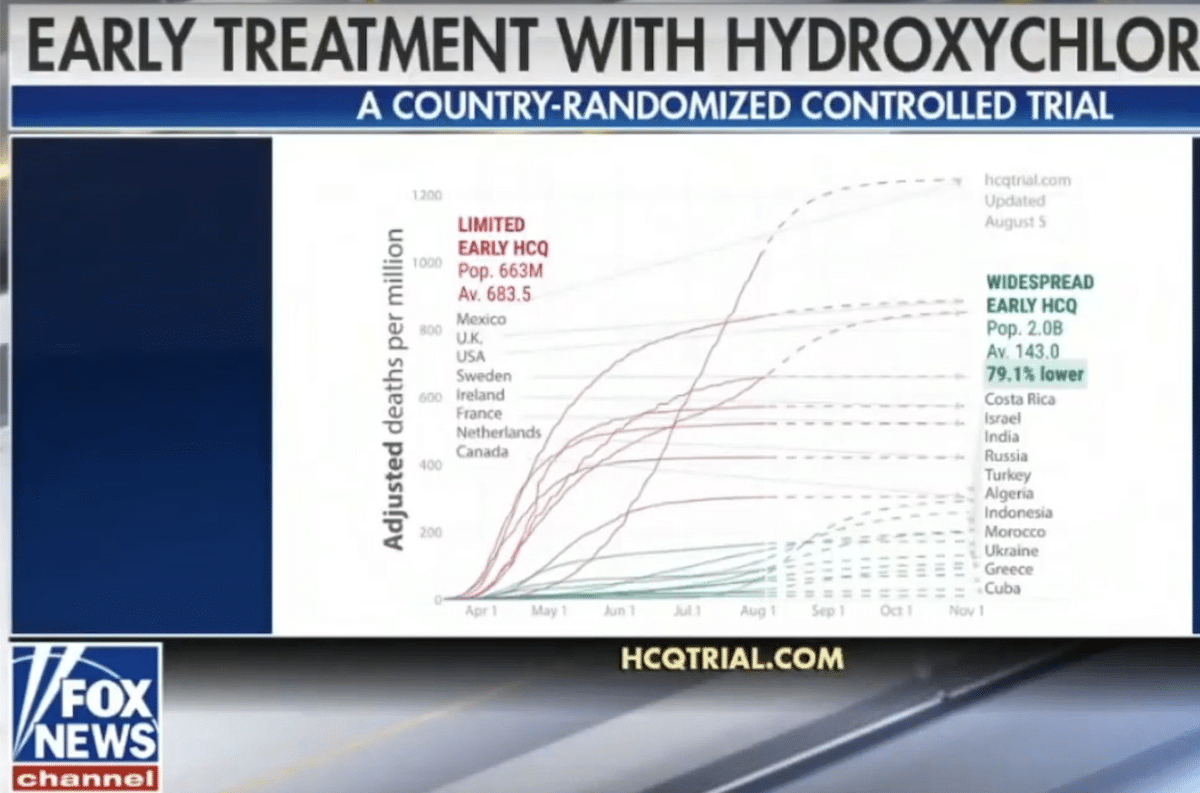

Large country-randomized controlled trial in 2.7 billion people shows 79.1% lower death rate in COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine

Verdict detail

Flawed reasoning: The “analysis” incorrectly assumes that all the individuals in the countries assigned to the hydroxychloroquine treatment group actually used hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 and that those in the control group did not (which would be required in a randomized controlled trial). Anecdotal evidence and/or the existence of policies on the use of hydroxychloroquine are not adequate to indicate its widespread usage among the population.

Cherry-picking: The authors conveniently excluded from the hydroxychloroquine group countries with high mortality rates such as Spain, Italy, and Brazil, and from the control group those with a low mortality rate such as Germany. Despite the authors’ claim to have excluded countries with an early widespread use of face masks, they still included Indonesia, which was one of them.

Misleading: The authors originally called their “analysis” a “country-randomized controlled trial”, which does not exist as it is not possible to randomize individuals to treatment groups based solely on the country in which they reside. Although the authors recently corrected the title, the misuse of the term attempts to give their publication the appearance of legitimacy. The analysis also misreports the results from recent clinical trials which found that hydroxychloroquine was not beneficial for COVID-19 patients.

Full Claim

“Many countries either adopted or declined early treatment [of COVID-19] with [hydroxychloroquine], forming a large country-randomized controlled trial with 2.0 billion people in the treatment group and 663 million in the control group; The [hydroxychloroquine] treatment group has a 79.1% lower death rate”

Review

On 5 August 2020, an “analysis” comparing COVID-19 mortality rates in countries with different practices regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine to treat the disease started circulating in social media posts on Facebook and Twitter. In the middle of an intense public debate about the safety and effectiveness of the drug as a COVID-19 treatment, the analysis claims that countries that adopted “widespread use” of hydroxychloroquine had a 79% lower COVID-19 death rate than those that highly limited its use. Even though this claim contradict the conclusions of the broader scientific community, they were nonetheless amplified by some U.S. news outlet with large audiences (such as Fox News) and by advocacy groups that support the use of hydroxychloroquine, resulting in the memes receiving hundreds of thousands of interactions in a single week, according to the social media analytics tool CrowdTangle.

This analysis was posted on the website CovidAnalysis, which is also the name of a Twitter account created in June 2020 that advocates for the use of hydroxychloroquine as COVID-19 treatment. CovidAnalysis appears to be connected with a network of other websites and Twitter accounts, some of whom are mentioned in the Acknowledgments section. These other websites and accounts also promote the use of hydroxychloroquine. Despite stating that the authors of the analysis are “PhD researchers, scientists, people who hope to make a contribution”, the website does not disclose the authors’ identities, affiliations, or potential conflicts of interest. The analysis was heavily criticized by scientists on social media for its flawed reasoning and biased methodology.

The main flaw in this analysis is the lack of evidence supporting the underlying assumption that individuals within the hydroxychloroquine group used the drug more often than people from the control group did. Without evidence that the treatment group was indeed treated, the results and conclusions from the analysis are unreliable. The implication that policies favouring the use of hydroxychloroquine reduced COVID-19 mortality results from cherry-picking or convenient exclusion of certain countries, as detailed below.

One of the challenges in evaluating the impact of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 at the country level is the lack of studies that quantify its use in different countries. The authors claim to have included 19 countries “that chose and maintained a clear assignment to one of the groups [control or hydroxychloroquine treatment] for a majority of the duration of their outbreak, either adopting widespread use or highly limiting use”. However, the assignment of each country into the treatment and control groups did not follow a standardized objective criteria, but mainly anecdotal evidence posted on social media (for example, the evidence for assigning Ireland into the control group can be seen here and here) that does not necessarily reflect hydroxychloroquine usage within those countries. In addition, over-the-counter and even online shopping make assignment of whole countries to one of the groups extremely challenging.

The authors also claim to have excluded countries which adopted “early widespread use of masks” in an attempt to significantly reduce COVID-19 spread. The authors state that their exclusion is based on the countries studied in this preprint (a study which has not been peer-reviewed by other scientists yet), which reported an association of lockdowns and mask-wearing with a lower country-wide COVID-19 mortality[1]. However, even though the preprint listed Indonesia among the countries with an early widespread use of masks, the analysis inexplicably included this country in the control group, when it should have been excluded based on their criteria. Also, the authors did not state the reasons for excluding countries with a population smaller than one million.

The analysis contains additional significant bias and methodological flaws, as we explain below.

The real sample size of the analysis is not 2.7 billion people, but rather the number of countries

Sample size is the number of measurements or observations used in one study, which in this case is the average death rates from the countries included in the analysis. The sample size affects p-values and confidence intervals, which are statistical parameters that allow us to determine whether the results observed are real and did not arise by chance. The incorrect use of such a large sample size can magnify effects which are in truth very small or not clinically relevant. The authors made all of their calculations using the sample size of 2.7 billion people, based on the population sizes of countries in both groups, which invalidates all their statistical analyses and the conclusions they drew from them. This number of 2.7 billion is two orders of magnitude higher than the total number of COVID-19 cases on the planet, making it a gross and obvious over-estimation. Beyond sample size, it is not possible to assess whether the statistical analysis is correct because the authors did not include a detailed Methods section, an essential element in any scientific publication.

The authors misreport the results of previous studies, which showed no benefit of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 patients

In the section titled Literature Review, the authors analyzed results from previous hydroxychloroquine studies in cells, animal models, and humans, incorrectly concluding that hydroxychloroquine was 100% effective to treat COVID-19 in cell cultures and as prevention or early treatment. This is false, as recent studies in cells and monkeys found no benefit of hydroxychloroquine for treating or preventing COVID-19 infection[2,3]. Furthermore, prophylactic and early use of hydroxychloroquine did not benefit COVID-19 patients in large clinical trials, as explained in previous reviews by Health Feedback.

To support this false claim, the authors misreport the findings from at least three randomized clinical trials (links here, here, and here) that reported no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine[4-6]. The authors of the analysis questioned the conclusions from these trials due to alleged methodological flaws such as fake surveys or small sample sizes, and reinterpreted the original results. Of note, those clinical trials involved hundreds of participants, a much larger sample size than 19 countries used by CovidAnalysis.

The comparison should not be performed on death per capita

To detect a potential influence of a drug on mortality, the authors should have compared the number of deaths per case of COVID-19 infection: that would inform us on whether the drug helped sick patients. Instead, they used the number of deaths per capita, which is misleading to compare countries since they have very different total numbers of infections.

The report is not a randomized clinical trial

As mentioned in a previous review by Health Feedback, randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for assessing the safety and efficacy of a new treatment. Such studies reduce potential bias by randomly assigning patients to either the control or test group, ensuring that demographics such as age, gender, disease severity, or comorbidities are equally represented in both groups. This allows us to be certain that any differences observed are the result of the different treatments provided. According to the analysis, “entire countries made different decisions regarding treatment with hydroxychloroquine, essentially assigning themself to the treatment or control group”, which they claim is an “essentially random” selection. But countries have different demographic distributions that can influence disease outcome, rendering comparison of drug efficacy at the national level unreliable.

The term “country-randomized controlled trial” does not exist, as the authors acknowledge in the report. The authors’ co-opting of the term “randomized controlled trial” in this case is not only misleading but also inaccurate, as the report would be best described as an observational ecological study. Such studies analyze data at the population level, rather than at the individual level, and are generally quick, inexpensive, and easy to conduct. However, they are also particularly prone to bias and confounding effects, including a specific type of confounder called the ecological fallacy. This fallacy occurs when the relationships observed among groups are wrongly applied to all the individuals within the group, making any conclusions based on the assumption unreliable.

A good example of the ecological fallacy appeared in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012 in which the author found a correlation between chocolate consumption and the number of Nobel laureates in a country (the full study can be read here)[7]. He incorrectly assumed that high chocolate consumption among the general population meant that Nobel laureates were also eating large amounts of chocolate. However, the author did not investigate whether this was actually true. Similarly, the authors of the CovidAnalysis incorrectly assumed that country policies favoring or limiting the use of hydroxychloroquine imply that all individuals infected with COVID-19 in those countries received or avoided, respectively, hydroxychloroquine treatment.

In summary, the report is an observational ecological analysis that divides countries into hydroxychloroquine treatment and control groups based on anecdotal evidence in order to compare COVID-19 mortality rate per million residents. The analysis contains significant bias and methodological flaws, including arbitrary inclusion criteria, false assumptions, and inappropriate statistical analysis, which completely invalidate its conclusions. The lower mortality that this analysis associates with the use of hydroxychloroquine is further undermined by the numerous large and robust clinical trials which suggest no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 patients.

We added a link to evidence of coordination among CovidAnalysis websites after publication.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Leffler et al. (2020) Association of country-wide coronavirus mortality with demographics, testing, lockdowns, and public wearing of masks. [Note: This is a pre-print that has not yet been peer reviewed or been published in a journal at the time of this review’s publication.]

- 2 – Hoffmann et al. (2020) Chloroquine does not inhibit infection of human lung cells with SARS-CoV-2. Nature.

- 3 – Maisonnasse et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine use against SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-human primates. Nature.

- 4 – Boulware et al. (2020) A randomized trial of hydroxychloroquine as postexposure prophylaxis for Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine.

- 5 – Skipper et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine in nonhospitalized adults with early COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- 6 – Mitjà et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine for Early Treatment of Adults with Mild Covid-19: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Clinical Infectious Disease.

- 7 – Messerli. (2012) Chocolate Consumption, Cognitive Function, and Nobel Laureates. The New England Journal of Medicine.

NOTES

This fact check is available at IFCN’s 2020 US Elections FactChat #Chatbot on WhatsApp. Click here, for more.