- Climate

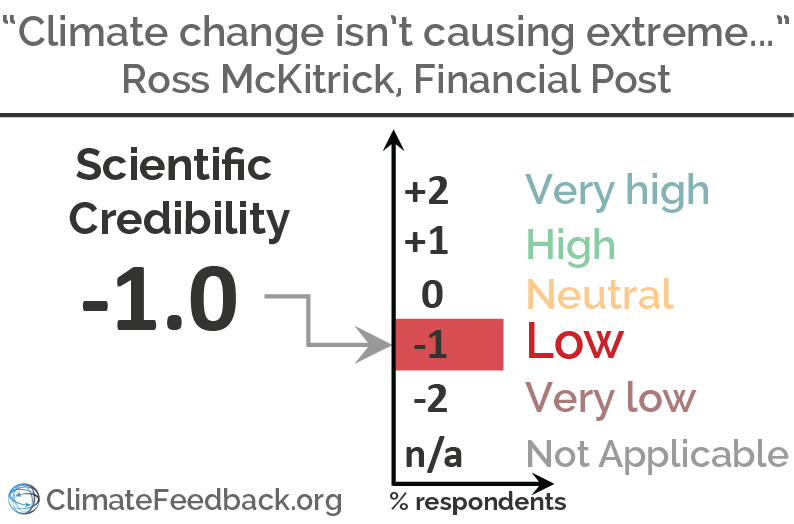

Financial Post commentary jumps to unsupported conclusions in claiming “climate change isn’t causing extreme weather”

Reviewed content

Headline: "This scientist proved climate change isn’t causing extreme weather — so politicians attacked"

Published in Financial Post, by Ross McKitrick, on 2019-06-07.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This op-ed published by the Financial Post, written by Ross McKitrick, describes a presentation by University of Colorado Boulder researcher Roger Pielke, Jr. The article misrepresents analyses of trends in US weather extreme damages as indicators of global trends in the weather extremes, themselves.

Researchers who reviewed the article explained that the US is not representative of the entire world. Trends in weather extremes are not always apparent from limited historical data, and can vary by region. Assessing observed trends is one piece of research on this topic, but an understanding of the physics of these weather events can also enable projections of future behavior that must also be considered. Overall, the evidence highlighted in the article—about certain types of extreme weather in some regions of the world—does not support its conclusion that “climate change isn’t causing extreme weather”.

UPDATE (24 June 2019): The Financial Post article has been updated with an editor’s note that reads “This article has been updated from its original version to specifically identify the major extreme weather indicators that have been shown to have no solid connection to climate change.” The examples given make the article a little less accurate rather than more, but this minor change does not significantly affect the conclusions of our reviewers.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context. You can also install the Hypothesis browser extension to read the scientists’ annotations in context.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall assessment of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Project Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

This article is misleading since it confuses changes in climate change impacts with changes in climate and weather extremes and it subjectively selects examples that support its message.

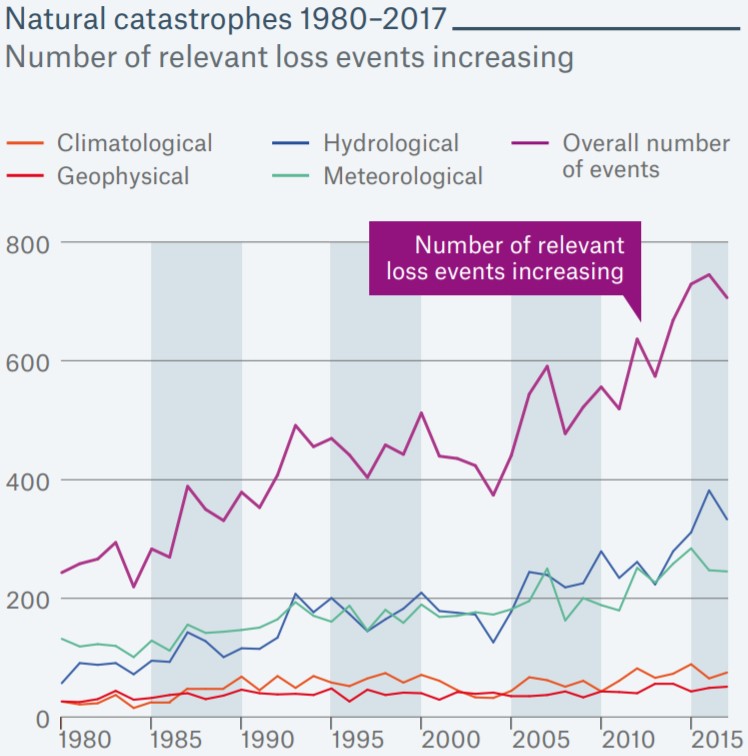

There is clear scientific evidence that many weather and climate extreme events increase in intensity and frequency due to anthropogenic climate change. Munich Re, for example, publishes data on global major extreme events in its annual reports.

While the number of geophysical extreme events (e.g. earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes) has stayed constant during the period 1980 to 2017, hydrologic extreme events and meteorological extremes increased significantly. The article is correct that increasing population and development is a primary contributor to increasing losses from extreme events. However, there is overwhelming evidence that climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of, specifically heat, coastal flooding, and rainfall-related extreme events1.

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

The arguments in this article are misleading for three reasons: (1) they mix the cost of the damage by extreme events with the actual physical phenomenon of the extreme event, (2) they only focus on data from the US, which is not representative of evidence in other regions, and (3) they completely ignore insights from climate projections, which are very clear on the link between global warming and an increase in extreme events.

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

The central claim in the story is that “climate change was not leading to higher rates of weather-related damages worldwide, once you correct for increasing population and wealth.”

Damage occurs when vulnerable infrastructure is exposed to bad weather, so the economic damage relates as much to the type of infrastructure as it does to the weather, so I will focus on the question of whether we have been seeing changes in extreme weather.

The Earth has been getting hotter, so certainly in terms of global and annual averages, the global weather has been getting more extreme. Further, many more places have been experiencing more extreme heat than would be expected by chance alone, so it is fairly safe to say that human-induced climate change has in many places been causing an increase in the frequency of extremely hot weather.

Storms are not like daily high temperatures, they occur sporadically and are difficult to forecast far in advance. That is, even if there were an increasing trend, it might not be possible to detect the climate signal through the randomness of weather. There is limited evidence supporting the idea that intense storms are becoming more frequent.

Studies of individual storms using computer models, where the storm conditions are simulated as observed and then again with the cooler sea-surface temperatures that would have prevailed in the absence of fossil-fuel CO2 emissions, have concluded that warmer sea surface temperatures are leading to stronger storms. However, if this signal is real, it is hard to detect in century scale trends in weather statistics.

While claims that extreme weather events are related to climate change in popular discourse often goes beyond the available data, we might want to be equally cautious in claiming that some extreme events are unrelated to climate change. (This climate.gov article gives some useful context.)

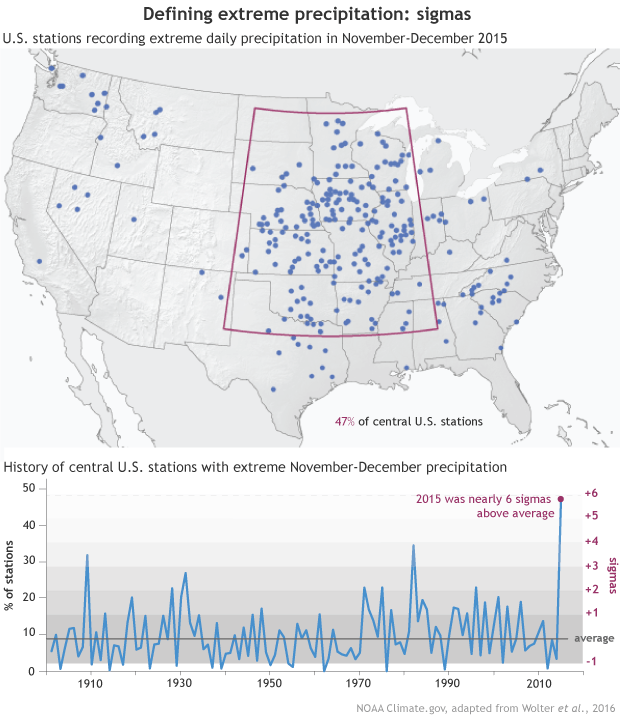

Sometimes we have data like this:

Can we say that that 2015 precipitation was not a consequence of climate change because there is no significant preceding trend, or do we say that the 2015 event was likely caused by climate change because there was no historical precedent? Obviously, the case is not clear. There are many people who today tend to attribute such anomalous events to climate change, regardless of a lack of underlying mechanistic understanding.

Uncertainty is not our friend. Uncertainty means that we are exposing ourselves to risk.

My general rule of thumb is: “If some weather happens that has never happened before, there is a good chance that climate change has played a role.” This is not a scientific finding but an exhibition of my personal bias. Of course, others may have different priors.

To get a broader perspective, people should be looking to the 2016 National Academy Report on Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change to see what scientists really think, as reflected in a well-respected consensus process:

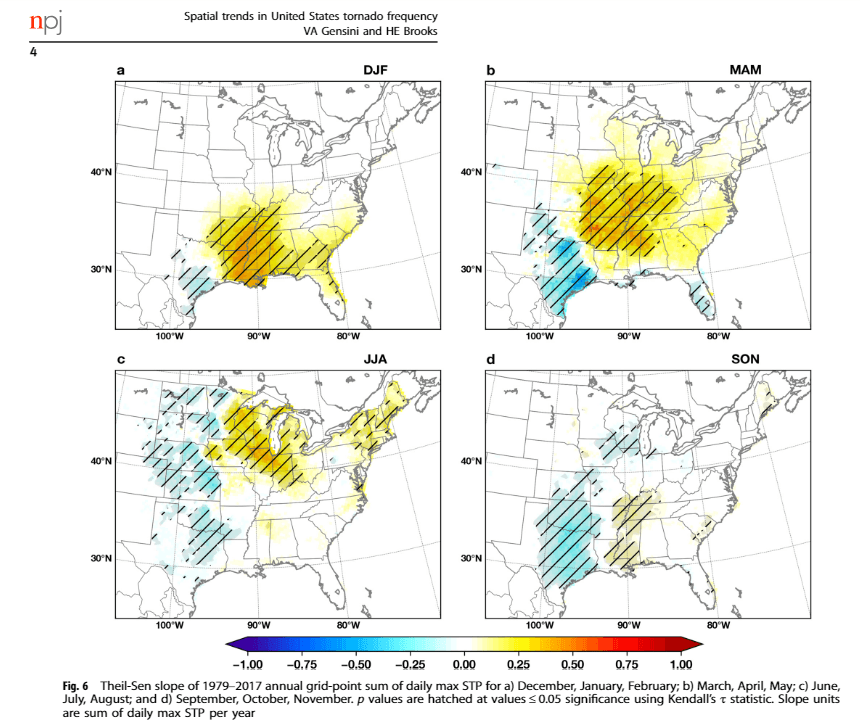

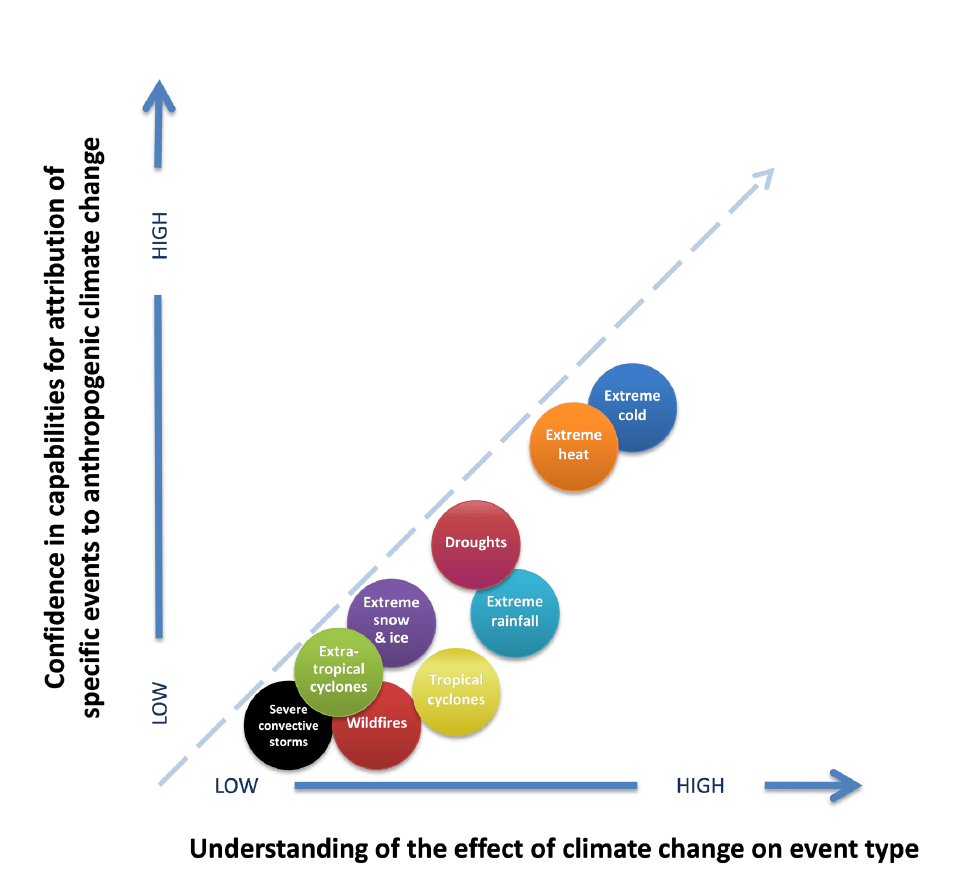

The figure below (from that report) shows that confidence on attributing changes in extreme hot and cold events to climate change is fairly high, but that the confidence level goes down the less the event has to do with temperature and the more it has to do with the hydrological cycle—and “severe convective storms” is the type of extreme event listed that has the lowest level of understanding and lowest confidence in attribution to climate change.

Source: National Academies of Science

Another useful report is Chapter 18 of the 2015 IPCC AR5 Working Group II report, also the product of a highly respected consensus process.

It should be noted that in the Technical Summary to Chapter 18, there was no reference to increases in intense storms, and while there is evidence of increased storminess in some regions such a trend is not yet statistically significant at global scale.

McKitrick does a service by calling attention to the relatively weak observation-based evidence for association of damage from extreme weather with climate change. Regardless of whether or not the reader finds compelling the evidence that climate change is increasing the number of intense storms, it is clear that climate change has been increasing the number of record hot days and heat spells. Thus the statements “Globally there’s no clear evidence of trends and patterns in extreme events” and “The bottom line is there’s no solid connection between climate change and the major indicators of extreme weather” would need to be regarded as false.

We can be fairly sure that with continued greenhouse gas emissions, future weather will contain many days that are outside of today’s range of normal weather variability, so we know that the number of “extreme” weather days will increase. There are questions regarding the extent to which we can detect that increases in extremes are already happening and the extent to which we can project the amount of climate damage associated with increases in these extremes.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Annotations

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

This scientist proved climate change isn’t causing extreme weather

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

This is misleading. The main argument of Pielke’s presentation at the University of Minnesota, the Hohenkammer Consensus Statement, and the IPCC reports is that the increasing COST due to extreme weather cannot be linked to climate change.

Associate Professor, University of Illinois

The title is misleading. He didn’t prove anything. He’s simply claiming there are not yet definitive links between climate change and some extreme events. I would refer the readers to the most recent National Climate Assessment1 for a broader and longer list of salient impacts of climate change beyond the short and narrow selection quoted.

- 1 – US NCA (2018) Volume II: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

The headline of this piece is incorrect. Nobody has “proved climate change isn’t causing extreme weather.” While just about everybody acknowledges that climate change is causing more record high temperatures and fewer record cold temperatures, the jury still is out on whether it can be said that climate change is causing other kinds of extreme weather, such as intense storms.

There is a tendency by many to attribute every extreme event to climate change, and while that is not justified, in most cases of extreme weather there is insufficient data and understanding to make a clear determination of the extent to which climate change may or may not have played a role.

While members of the media may nod along to such claims [about changes in weather extremes], the evidence paints a different story

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

This is again misleading. The evidence that is mentioned in this article is only one part of the complete picture. It focuses only on North America and only on the observational period. It neglects observational evidence from other regions in the world and the insights from climate projections.

They concluded that trends toward rising climate damages were mainly due to increased population and economic activity in the path of storms, that it was not currently possible to determine the portion of damages attributable to greenhouse gases, and that they didn’t expect that situation to change in the near future.

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

This is true, but it is only one of 20 conclusions from the Hohenkammer Statement. Another conclusion, for example, is: “For future decades the IPCC (2001) expects increases in the occurrence and/or intensity of some extreme events as a result of anthropogenic climate change. Such increases will further increase losses in the absence of disaster reduction measures.”

Globally there’s no clear evidence of trends and patterns in extreme events such as droughts, hurricanes and floods. Some regions experience more, some less and some no trend. Limitations of data and inconsistencies in patterns prevent confident claims about global trends one way or another. There’s no trend in U.S. hurricane landfall frequency or intensity. If anything, the past 50 years has been relatively quiet. There’s no trend in hurricane-related flooding in the U.S. Nor is there evidence of an increase in floods globally. Since 1965, more parts of the U.S. have seen a decrease in flooding than have seen an increase. And from 1940 to today, flood damage as a percentage of GDP has fallen to less than 0.05 per cent per year from about 0.2 per cent.

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

This is more or less a summary of the data cited in Pielke’s presentation and probably accurate. But as mentioned above, it does not give the whole picture.

(1) The observational data for the US does not reflect changes in other regions. Heat waves in other regions can, for example, already be linked to climate change: “It is

very likely that the number of cold days and nights has decreased and the number of warm days and nights has increased on the global scale. It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia. It is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed global scale changes in the frequency and intensity of daily temperature extremes since the mid-20th century. It is likely that human influence has more than doubled the probability of occurrence of heat waves in some locations. (IPCC1)

(2) The main argument for linking extreme weather with climate change comes from climate projections, which are completely omitted here. The IPCC special report on the 1.5 degree target2 is very clear in stating that a global warming of 2 degrees will lead to more extreme events than global warming of 1.5 degrees: “Climate models project robust differences in regional climate between present-day and global warming up to 1.5°C, and between 1.5°C and 2°C (high confidence), depending on the variable and region in question (high confidence). Large, robust and widespread differences are expected for temperature extremes (high confidence).” and “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would limit risks of increases in heavy precipitation events on a global scale and in several regions compared to conditions at 2°C global warming (medium confidence). ” These are only summary statements, but detailed elaboration is given within the report.

- 1 – IPCC (2013) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis

- 2 – IPCC (2018) Global Warming of 1.5 °C

Associate Professor, University of Illinois

Tropical cyclones are extreme and rare events thus statistically significant changes are difficult to detect especially given the limitations in historical observations before satellite coverage, but overall coastal flooding is becoming much more of a problem under global warming as sea levels rise. This will only get worse in the future.

Some regions experience more, some less and some no trend. Limitations of data and inconsistencies in patterns prevent confident claims about global trends one way or another.

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

Confidence is often low due to the limited data availability. As also stated by the IPCC, low confidence does not necessarily imply that a link does not exist.

There’s no trend in global droughts. Cold snaps in the U.S. are down but, unexpectedly, so are heatwaves.

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

Yes, but not in other regions of the world (see annotations above).

Associate Professor, University of Illinois

The temperature claims are a bit misleading. We experience more and more record breaking warm temperatures over time due to global warming. These changes are damaging for many reasons beyond drought.

The bottom line is there’s no solid connection between climate change and the major indicators of extreme weather

Postdoctoral research fellow, Helmholtz Zentrum Geesthacht

As stated in my comments above, this conclusion is not valid. It is based on incomplete reasoning. The argumentation in the article confuses the occurrence of events with their cost, neglects observational evidence from other regions than the US, and completely omits insight from climate projections. The fact that it is still difficult/impossible to attribute individual extreme events to climate change in the observational record makes it easy to say that the link between global warming and increasing extreme events does not exist. But projections are very clear, and the fact that we cannot detect the links in all observations YET does not mean that it will not emerge when the warming signal increases. See also e.g. Suarez-Gutierrez et al1 for a discussion of the role of internal natural variability in distinguishing between different warming regimes.

- 1 – Suarez-Gutierrez et al (2018) Internal variability in European summer temperatures at 1.5 °C and 2 °C of global warming, Environmental Research Letters