- Climate

Some extreme weather events are clearly becoming more common, in contrast to Lord Lawson's claim

Key takeaway

Globally, there has been a clear increase in certain weather extremes including heat waves and intense rainfall events.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is sort of the voice of the consensus, concedes that there has been no increase in extreme weather events.

Verdict detail

Misrepresents source: The 2013 IPCC report identifies some extreme events for which trends are unclear, but it also identifies certain types of weather extremes that research shows are clearly increasing, like heat waves and intense rainfall.

Full Claim

[Al Gore] said that there had been a growing increase, which had been continuing, in the extreme weather events. There hasn’t been. All the experts say there haven’t been. The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is sort of the voice of the consensus, concedes that there has been no increase in extreme weather events. Extreme weather events have always happened. They come and go. And some kinds of extreme weather events of a particular time increase, whereas others, like tropical storms, diminish…

Project Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

This is a false statement since the IPCC AR5 even states in its summary for policy makers that “Human influence has been detected … in changes in some climate extremes”. In this report it is also stated that: “It is now very likely that human influence has contributed to observed global scale changes in the frequency and intensity of daily temperature extremes since the mid-20th century, and likely that human influence has more than doubled the probability of occurrence of heat waves in some locations” and “It is virtually certain that there will be more frequent hot and fewer cold temperature extremes over most land areas on daily and seasonal timescales as global mean temperatures increase. It is very likely that heat waves will occur with a higher frequency and duration.”

Since the publication of the IPCC AR5 many studies where published on the detection and attribution of man made impacts on climate extremes. An example which shows the human influence on precipitation extremes is Fischer and Knutti (2015)*.

- Fischer and Knutti (2015) Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavy-precipitation and high-temperature extremes, Nature Climate Change

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

A good place to go for IPCC conclusions related to extreme events is the Summary for Policy Makers of the 2012 IPCC “SREX”1 and 2014 Synthesis reports2.

The 2014 Synthesis Report concludes:

“Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950. Some of these changes have been linked to human influences, including a decrease in cold temperature extremes, an increase in warm temperature extremes, an increase in extreme high sea levels and an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events in a number of regions…. It is very likely that the number of cold days and nights has decreased and the number of warm days and nights has increased on the global scale. It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia. It is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed global scale changes in the frequency and intensity of daily temperature extremes since the mid-20th century. It is likely that human influence has more than doubled the probability of occurrence of heat waves in some locations.”

Thus, Lord Lawson’s statement is false.

On the other hand, in the Synthesis Report, the IPCC also states:

“There is low confidence that anthropogenic climate change has affected the frequency and magnitude of fluvial floods on a global scale. … There is low confidence in observed global-scale trends in droughts, due to lack of direct observations, dependencies of inferred trends on the choice of the definition for drought, and due to geographical inconsistencies in drought trends. … There is low confidence that long-term changes in tropical cyclone activity are robust, and there is low confidence in the attribution of global changes to any particular cause. However, it is virtually certain that intense tropical cyclone activity has increased in the North Atlantic since 1970.”

Thus, there are many extreme events occurring which likely bear little or no relationship to climate change, and this may be what Lord Lawson was attempting to point out. While true, this does not mean that climate change is not contributing to increases in some kinds of extreme events.

- 1- IPCC (2012) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation

- 2- IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report

Postdoctoral researcher, Los Alamos National Laboratory

Lord Lawson’s blanket claim that the frequency of extreme events has not increased is wrong. Due to overall warming, for example, it is very clear in observations that the frequency and severity of extreme heat events is increasing, and that this increase would not occur in the absence of anthropogenic forcing.

Research Scientist, University of Colorado, Boulder

This statement is not true. The IPCC issued a 2012 report on “Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation”1. Even within the Summary for Policymakers, the report lists the evidence of changes in extreme weather and climate events. Changes are different depending on the location (e.g. more intense and longer droughts in southern Europe and West Africa, while this is not true in North American and northwestern Australia), but changes in extremes have been documented across the globe (with low to high confidence depending on the type of event and location).

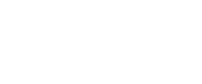

The IPCC AR5 Summary for Policymakers2 states: “Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950 (see Table SPM.1 for details). It is very likely that the number of cold days and nights has decreased and the number of warm days and nights has increased on the global scale. It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia. There are likely more land regions where the number of heavy precipitation events has increased than where it has decreased. The frequency or intensity of heavy precipitation events has likely increased in North America and Europe. In other continents, confidence in changes in heavy precipitation events is at most medium.” It also notes: “There has been further strengthening of the evidence for human influence on temperature extremes since the SREX. It is now very likely that human influence has contributed to observed global scale changes in the frequency and intensity of daily temperature extremes since the mid-20th century, and likely that human influence has more than doubled the probability of occurrence of heat waves in some locations.”

Note that it’s possible to cherry pick types of extreme events and locations to argue that there is no evidence.

Also, perhaps even more important than whether extremes have already changed is that there is high certainty of changes in a number of important extremes over the coming decades.

- 1- IPCC (2012) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation

- 2- IPCC (2013) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis

Professor, Columbia University

The statement, though often repeated, is patently false. Clear increases have been documented in the frequencies and intensities of heat waves and extreme precipitation events. There are other kinds of events for which there are no trends, and then others for which it is not clear whether there are trends, because natural variability is difficult to separate from long-term trends in short historical records. And indeed predictions about what global warming should do to extreme events vary from one kind of event to the next. But the observed increases in heat waves and extreme rain events are right in line with what is expected based on the predictions. And, because of the confounding effect of natural variability, there are some changes that we shouldn’t expect to see clearly yet, even though we are pretty confident that we will eventually. These include increasing intensity of tropical cyclones, and increasing occurrence of hydrological droughts and wildfires in many places.

Climate Scientist, University of California, Los Angeles

The specific claim here–that the IPCC scientific reviews find no increase in extremes–is incorrect, as is the broader implication that there is no observational evidence for increasing meteorological extremes. The IPCC Special Report on Managing the Risk of Extreme Events (SREX) directly contradicts the former claim, while a rapidly growing body of scientific research points toward a clear increase in certain types of extreme weather events–especially heat waves, droughts, and heavy downpours (e.g., Diffenbaugh et al. 2017)*. While it is certainly true that some of these extreme events would have occurred naturally (and that not all event types are increasing in all regions), human-caused global warming is exerting an increasingly substantial influence on the risk of global temperature and precipitation extremes.

- Diffenbaugh et al. (2017) Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme climate events. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Principal Research Fellow, National Centre for Atmospheric Science

The statement about the IPCC is incorrect. The 5th Assessment Report of the IPCC actually states in the Summary for Policymakers that: “Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950.”

It goes on to give specific examples: “It is very likely that the number of cold days and nights has decreased and the number of warm days and nights has increased on the global scale. It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia. There are likely more land regions where the number of heavy precipitation events has increased than where it has decreased. The frequency or intensity of heavy precipitation events has likely increased in North America and Europe.”

The statement that “extreme weather events have always happened” is misleading. Yes, extreme weather events have always happened, but many of them show long-term trends in frequency and/or intensity, as the IPCC AR5 states. For other types of extreme event we would not have expected to clearly see a long-term change given the warming to date, but would expect to see significant changes at higher warming levels.

Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter

This statement is not true. The IPCC does not say that “there has been no increase in extreme weather events”. In the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report, in the Physical Science volume, the very first table of the summary document gives a comprehensive, careful and nuanced assessment of different types of extreme weather events and whether there has been an increase in them. The IPCC’s conclusion is that for some types of extreme weather event, such as hot days, heatwaves and heavy precipitation, there have been increases (with varying levels of confidence and likelihood attached to these conclusions, ranging from “very likely” to “medium confidence. For other types of extreme weather events, such as drought and tropical cyclones, there is low confidence in a global-scale trend but nevertheless increases in some more localized regions are likely to have occurred.

Research fellow, University of Melbourne

Using the vague term “extreme weather”, Lord Lawson argues there has been no increase in such events. He then makes a specific reference to tropical storms for which it is true that while we are seeing signs of change in some characteristics we are not seeing an increase in their overall number.

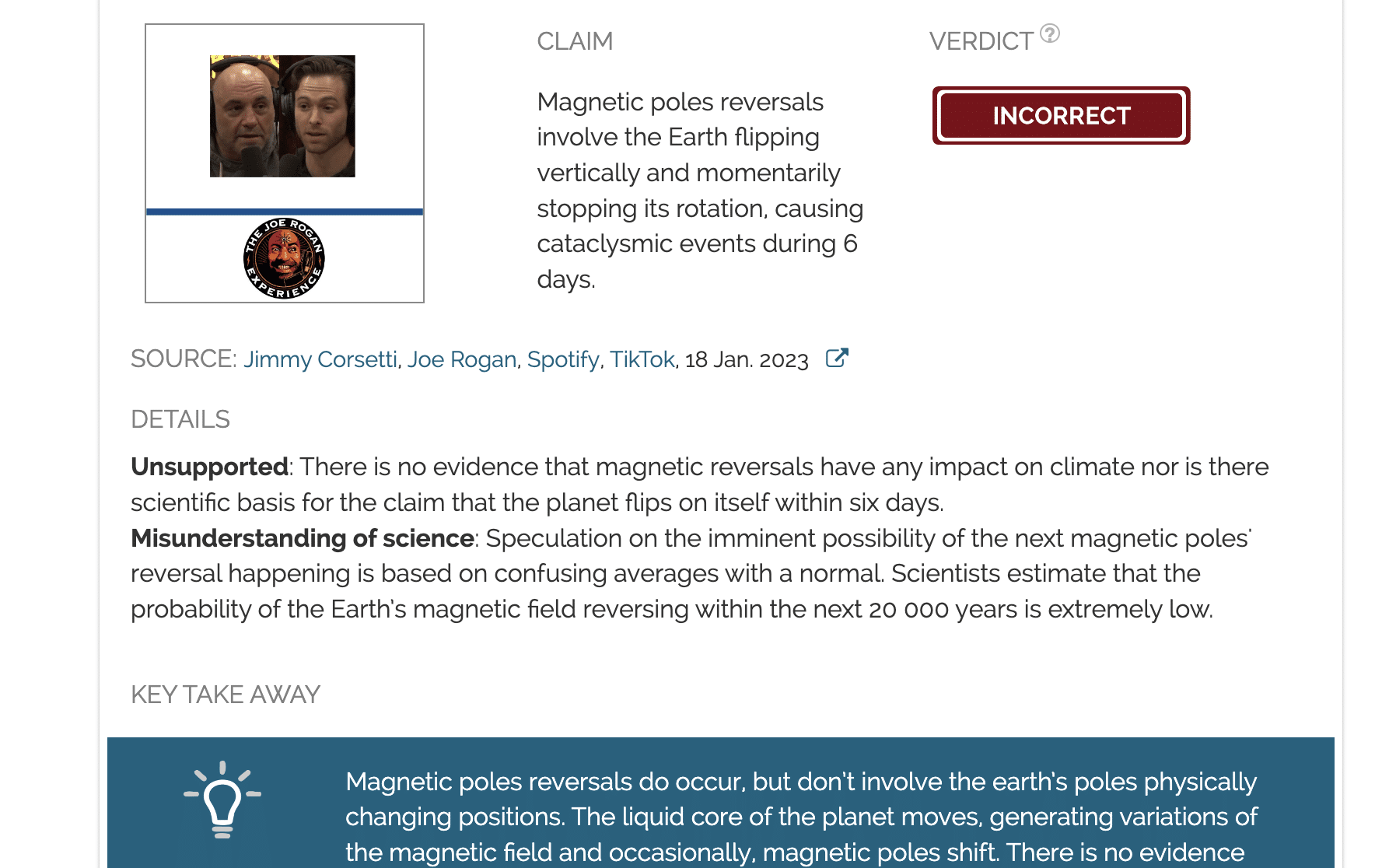

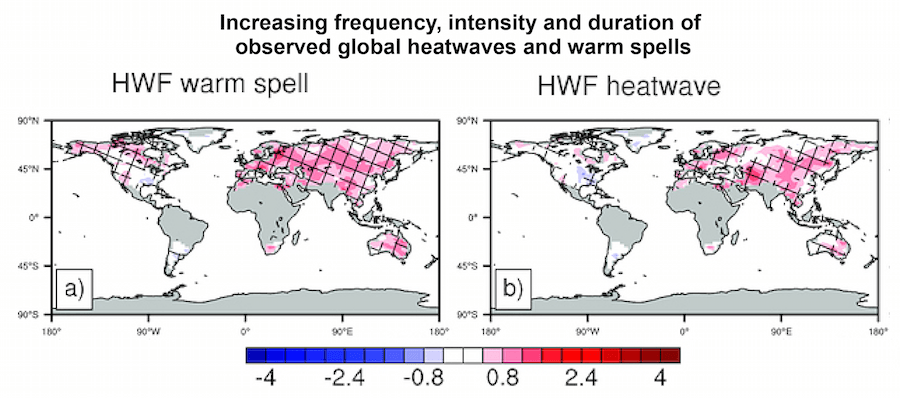

However, if we look at other types of extreme weather that cause greater numbers of fatalities, such as heatwaves, then Lord Lawson is incorrect. Heatwaves impact human health[1], and can compound the effects of drought and famine. The intensity, frequency and duration of heatwaves around the world is on the rise due to human-caused climate change[2].

Figure – Warm spell and heatwave trends in the number of days participating in an event, in which conditions persist for at least three consecutive days. Trends are for the period 1950–2011. Units are percentage of days per season/decade. Hatching represents where trends are significant at the 5% level, and grey indicates areas where there are insufficient observations for this study. Source: Perkins et al (2012)

- 1- Perkins et al (2012) Increasing frequency, intensity and duration of observed global heatwaves and warm spells. Geophysical Research Letters

- 2- Mitchell et al (2016) Attributing human mortality during extreme heat waves to anthropogenic climate change. Environmental Research Letters