- Health

Data doesn’t show that vaccines are responsible for 2022 excess mortality, contrary to Alex Berenson’s claim

Key takeaway

Many countries experienced excess mortality in 2022. This is likely the result of many factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic’s aftermath or the strain on healthcare systems. Moreover, since the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines in January 2021, countries with higher vaccine coverage have so far experienced less excess mortality on the whole than countries with lower vaccine coverage.

Reviewed content

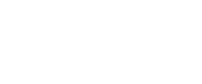

Verdict:

Claim:

COVID-19 vaccination is associated with all-cause excess mortality

Verdict detail

Cherry-picking: The claim’s argument relies on a correlation between vaccine coverage and excess mortality in the later months of 2022. However, previous months didn’t show this correlation. In fact, if we look at the entire time period since vaccination started in January 2021, it shows that countries with a higher vaccine coverage experienced less excess mortality.

Inadequate support: The claim relies on country-level data, such as the percentage of vaccinated people, when individual-level data, such as the vaccination status of people who died, would have been necessary.

Full Claim

COVID-19 vaccination is associated with all-cause excess mortality; “the death surge in highly mRNA vaccinated countries continues”; “less-vaccinated countries are reporting normal or below normal mortality rates”

Review

Many countries experienced some level of excess mortality throughout 2022. Excess mortality is determined by comparing how many people were expected to have died based on the previous years’ mortality with how many people actually died. For instance, the number of deaths in November 2022 in the European Union (EU) was 6.7% higher than during the 2016-2019 period.

As 2021 and 2022 also saw the general rollouts of COVID-19 vaccines—both the primary series and the booster shots—in most countries, some social media commentators claimed the vaccines are the culprit for this excess mortality. Health Feedback previously found that this claim was unsupported.

One other example of such claim is a Substack article by journalist Alex Berenson, claiming that “the death surge in highly mRNA vaccinated countries continue[d]” while “less-vaccinated countries are reporting normal or below normal mortality rates”. Berenson also posted the claim on Instagram, receiving more than 3,300 likes. Berenson has previously made several inaccurate claims about COVID-19 or vaccination.

Although Berenson acknowledged that “no connection [between COVID-19 vaccines and excess deaths] has yet been proven”, he implied a connection by adding “Most wealthy countries that relied on mRNA Covid shots and boosters had non-Covid deaths well above normal in 2022. The problem has worsened in recent weeks, in the wake of the fall Omicron booster campaigns.” However, this claim is unsupported by scientific evidence.

To verify this claim, one of the first things we can check is whether there’s indeed a correlation between the vaccine coverage of countries and excess all-cause mortality. It’s important to keep the caveat in mind that a correlation between vaccination coverage and excess mortality alone is insufficient to confirm that vaccination caused the excess deaths. Indeed, correlation alone isn’t enough to prove causation, as Health Feedback previously explained. But it is an important first step.

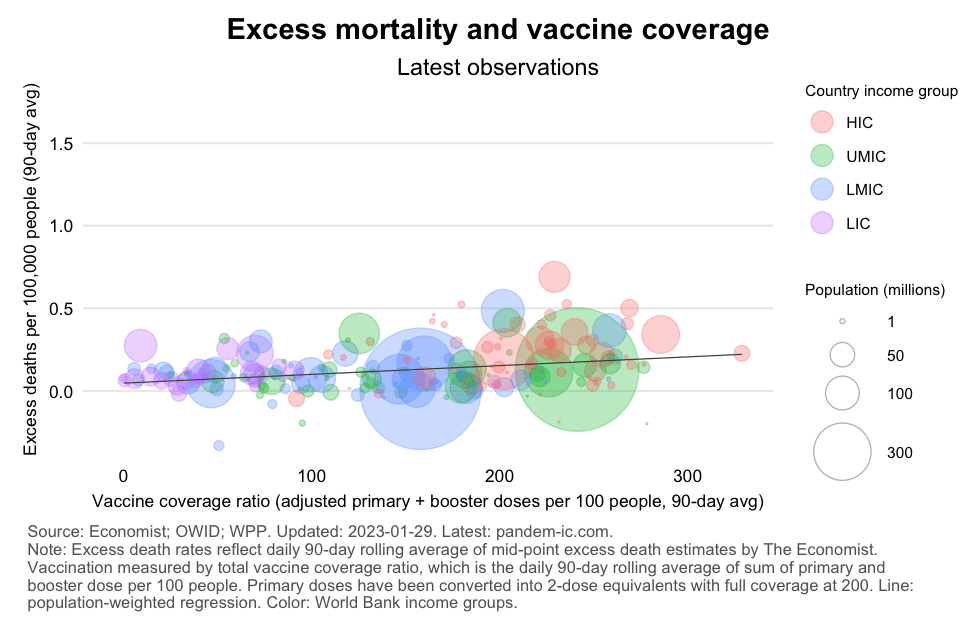

The website pandem-ic.com, run by Philipp Schellekens, an economic advisor at the World Bank, compared the vaccine coverage of world countries with their excess mortality. As shown in Figure 1, we can observe a slightly positive correlation between vaccine coverage and excess deaths in January 2023.

Figure 1. Correlation of excess mortality and vaccine coverage in countries of various income levels in January 2023 (90-day rolling average). Excess mortality data was derived from The Economist’s excess mortality tracker. Vaccine coverage data was obtained from the site Our World in Data, which gathers data from health authorities across the world. Excess mortality was expressed as a proportion of a country’s population size. Each country is represented by a circle proportional to its population size. HIC: high-income countries; UMIC: upper middle-income countries; LMIC: lower middle-income countries; LIC: lower-income countries. Source: Phillipp Schellekens.

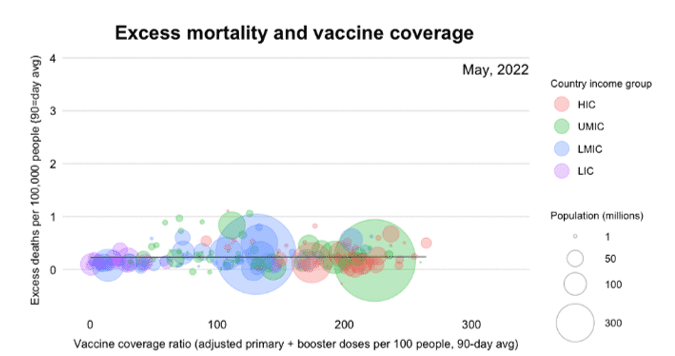

However, this correlation only appears at specific time points, mostly December 2022 and January 2023. In previous months, like May 2022 for example, the animated graph showed no correlation, or even a negative correlation, meaning that the excess mortality was lower in countries with a higher vaccination coverage, like in June 2021 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlation of average excess mortality and average vaccine coverage in countries of various income levels in May 2022. Excess mortality data was derived from The Economist’s excess mortality tracker. Vaccine coverage data was obtained from the site Our World in Data, which gathers data from health authorities across the world. Excess mortality was expressed as a proportion of a country’s population size. Each country is represented by a circle proportional to its population size. HIC: high-income countries; , UMIC: upper middle-income countries; , LMIC: lower middle-income countries; LIC: lower-income countries. Source: Phillipp Schellekens.

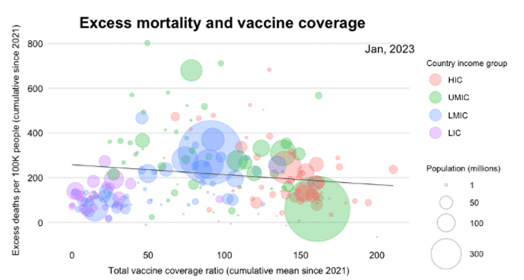

To get a better idea of how much excess mortality countries observed post-vaccine rollout, we need to look at the cumulative excess mortality instead—the sum of all excess deaths since the vaccines were introduced, rather than excess mortality for only one or two months.

And when we look at the cumulative excess mortality since January 2021—at the beginning of the global vaccine rollout—up to January 2023, we can see that countries with a higher vaccine coverage actually observed less excess mortality, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Correlation of the cumulative excess mortality since January 2021 and the vaccine coverage in the world’s countries. Excess mortality data was derived from The Economist’s excess mortality tracker. Vaccine coverage data was obtained from the site Our World in Data, which gathers data from health authorities across the world. Excess mortality was expressed as a proportion of a country’s population size. Each country is represented by a circle proportional to its population size. Countries are divided and color-coded into four levels of incomes. Source: Phillipp Schellekens.

Therefore, taking a correlation between excess mortality and vaccination during just one given month, as Berenson did, in order to imply that vaccination caused excess mortality is misleading. This is because this doesn’t present the whole picture that tells a completely different story: overall, the excess mortality has been lower since the beginning of the vaccination campaign in countries with a higher vaccine coverage.

If COVID-19 vaccines were somehow responsible for the ongoing excess mortality, we could hypothesize that the more vaccine doses administered, the more excess deaths would be registered.

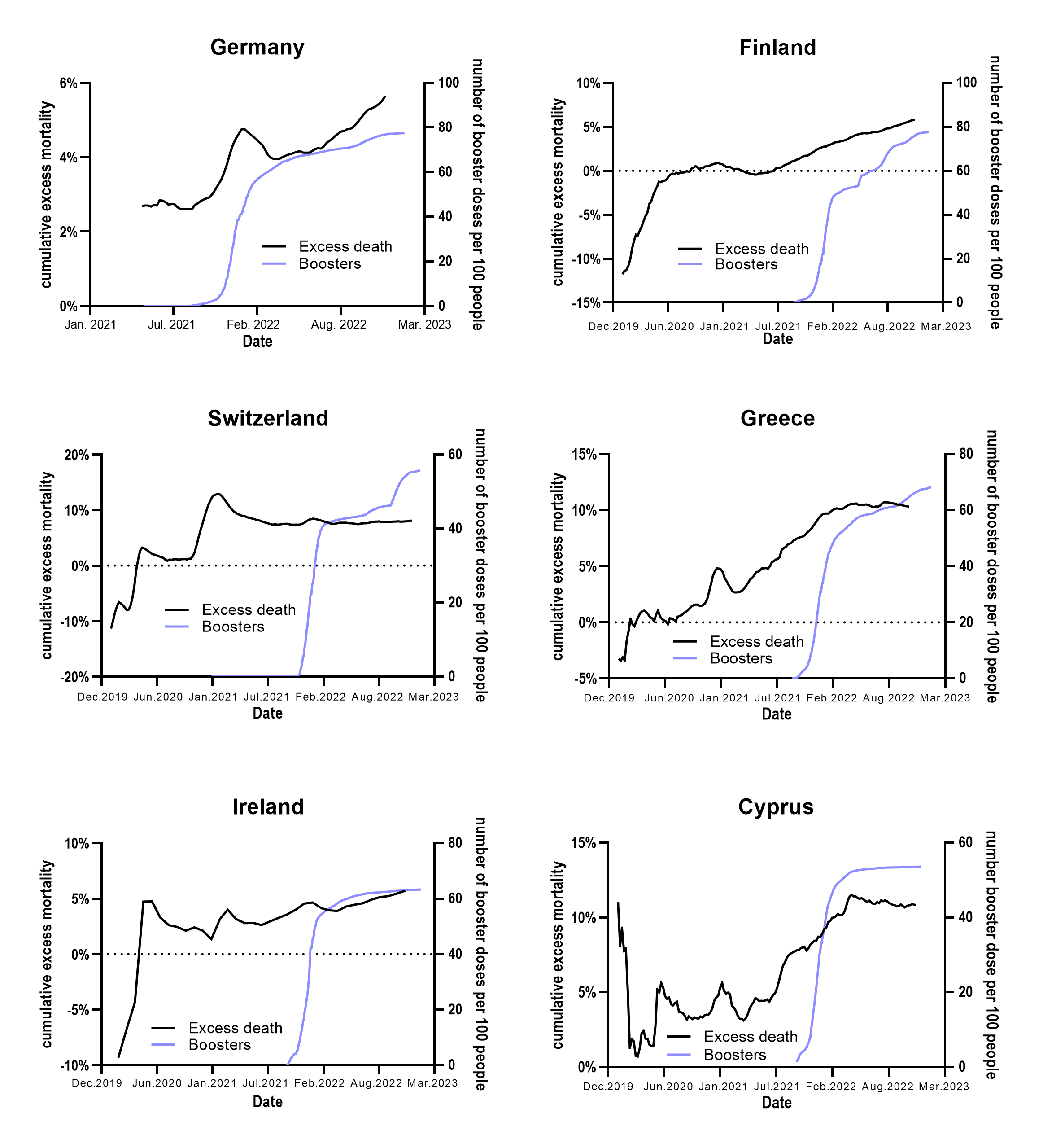

To test this hypothesis, we compared the number of vaccine booster doses administered with the cumulative excess deaths from the five countries which were experiencing the highest excess mortality based on the latest data available at Eurostat. We also included Switzerland, as it was cited as an example by Berenson, but excluded the Netherlands as its available data ended in September 2022 as shown on this graph.

As shown in Figure 4, the change in excess mortality doesn’t reflect changes in the number of administered booster shots. In Switzerland and Ireland, the cumulative number of deaths didn’t change much when the number of booster doses began to sharply rise.

In Greece, Cyprus and Finland, the excess mortality rose before the number of booster shots administered began to rise.

In Germany and Finland, both excess deaths and the number of booster shots administered rose steadily over the course of 2022 but at a different pace. In Germany the excess deaths rose faster than the number of booster shots administered, whereas the opposite happened in Finland.

In summary, there is no obvious and reproducible pattern of correlation between excess mortality and the number of booster doses administered, which is inconsistent with the alleged causal association between vaccination and excess mortality.

Figure 4. A correlation of boosters administered and cumulative excess deaths in the five countries which experienced the highest excess mortality based on latest Eurostat data to date. Also included is Switzerland, cited by Berenson in his article. Excess mortality is calculated as the difference between the cumulative registered all-cause deaths starting from 1 January 2020 and the cumulative number of expected deaths over the same period. The graph shows the difference as a percentage of the cumulative number of expected deaths. More details on cumulative excess mortality here. Boosters administered is expressed as the number of booster doses administered by 100 inhabitants. Both excess mortality and booster data used in the graph come from the site Our World in Data.

Claims about a connection between vaccination and excess deaths also overlook the fact that these data are available at the country level, but we don’t have data on the individual level. Specifically, we don’t know the vaccination status of the persons who died.

Drawing conclusions on individuals based on countries’ population average is known as the ecological fallacy and may lead to erroneous conclusions. In fact, studies at the individual level didn’t show that vaccinated people have higher all-cause mortality[1,2].

In summary, allegations that COVID-19 vaccines may be responsible for excess mortality in 2022 are unfounded. Data obtained at the country level don’t provide information on the vaccination status of people who died.

Furthermore, even if excess mortality was higher in some countries with higher vaccine coverage during certain months, when we look at the big picture, we find that countries with higher vaccine coverage experienced lower excess mortality since the vaccine rollout.

Causes of excess mortality are numerous, ranging from heat waves during the summer, COVID-19 itself, to struggling healthcare systems, as Health Feedback previously explained in an Insight article. No data indicate that COVID-19 vaccination increases all-cause mortality. On the contrary, studies found that vaccinated people were less likely to die compared to unvaccinated people.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Tu et al. (2023) SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death in Vaccinated and Infected Individuals by Age Groups in Indiana, 2021‒2022. American Journal of Public Health

- 2 – Xu et al. (2021) COVID-19 Vaccination and Non–COVID-19 Mortality Risk — Seven Integrated Health Care Organizations, United States, December 14, 2020–July 31, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.