- Health

COVID-19 vaccines start to provide protection within two weeks of the first dose, with no evidence they increase the risk of infection before then

Key takeaway

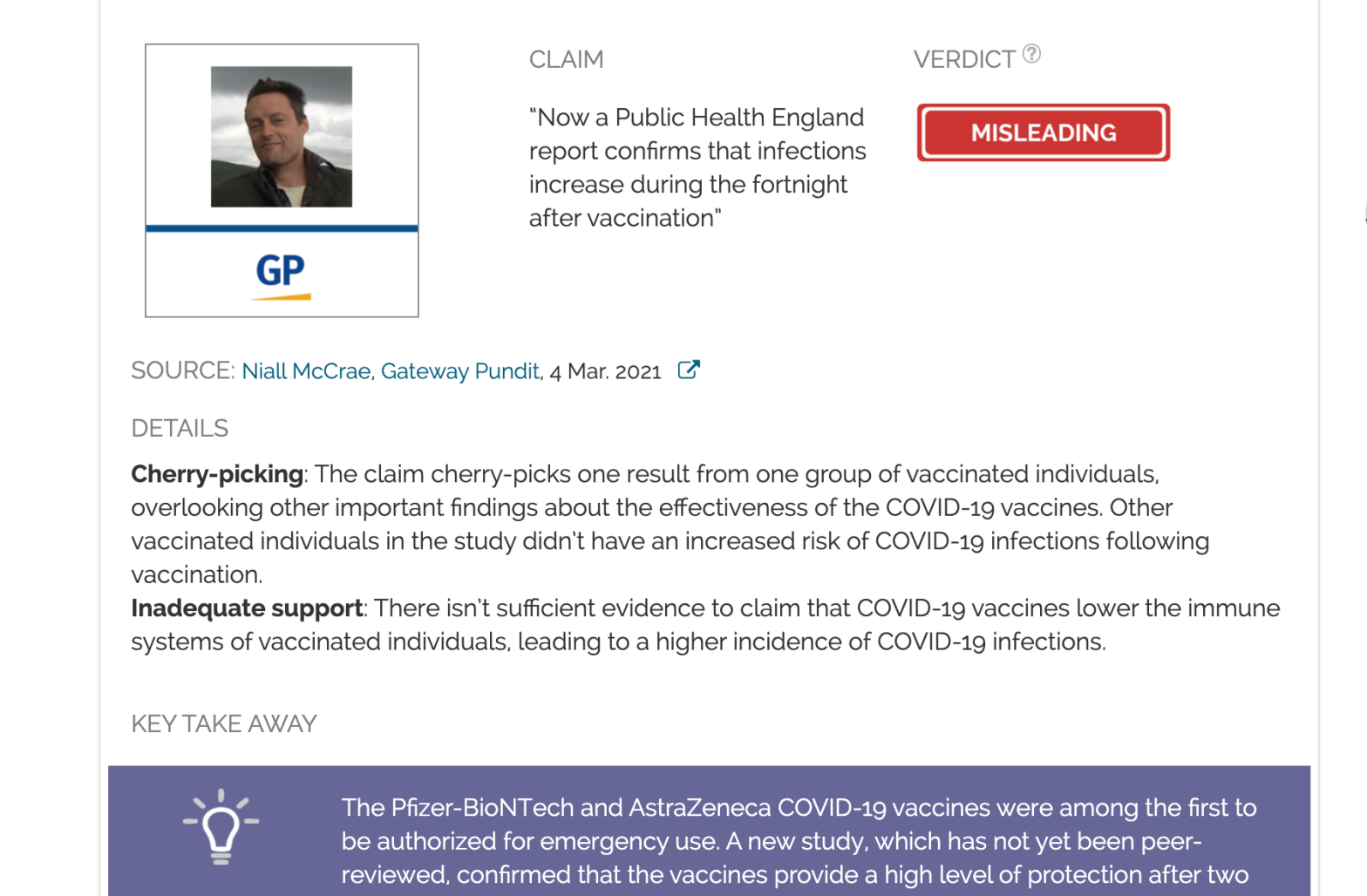

The Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines were among the first to be authorized for emergency use. A new study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, confirmed that the vaccines provide a high level of protection after two weeks against COVID-19 hospitalizations and death. An observation that the risk of COVID-19 infection increased in the first nine days after vaccination was only seen in the first group of elderly people vaccinated. This observation might be due to their higher pre-existing risk of COVID-19 infections, rather than an effect of the vaccine. No such effect was seen when vaccination was expanded to a wider group of people.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

“Now a Public Health England report confirms that infections increase during the fortnight after vaccination”

Verdict detail

Cherry-picking: The claim cherry-picks one result from one group of vaccinated individuals, overlooking other important findings about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines. Other vaccinated individuals in the study didn’t have an increased risk of COVID-19 infections following vaccination.

Inadequate support: There isn’t sufficient evidence to claim that COVID-19 vaccines lower the immune systems of vaccinated individuals, leading to a higher incidence of COVID-19 infections.

Full Claim

“Now a Public Health England report confirms that infections increase during the fortnight after vaccination”; “The Public Health England study, which was hailed by health secretary Matt Hancock for the reported 80% decrease in hospitalizations, actually showed a 48% rise in infections after the first dose of Pfizer and Astra Zeneca vaccines.”; “This is what may be happening. Vulnerable people who unknowingly had Covid-19 or whose immune system was keeping it at bay, succumbed to the disease after the vaccine lowered their immunity. The virus struck hard, leading to severe symptoms, cytokine storm and pneumonia.”

Review

A Gateway Pundit article by Niall McCrae claimed that a report from Public Health England showed a “48% rise in infections after the first dose of Pfizer and Astra Zeneca vaccines”.

The report from Public Health England, which was released on 1 March and has not yet been peer-reviewed, estimated the real-world effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines on COVID-19 diagnoses, hospitalizations, and deaths[1].

During the study period, the length of time between administering the first and second doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine increased from three weeks to twelve weeks in England, which provided researchers an opportunity to evaluate the effects of a single vaccine dose in the population.

The study was a “negative test case control study”, where vaccination status is compared between people who tested positive or negative for COVID-19. By comparing to people who were tested negative, the researchers can control for factors such as differences in health-seeking behavior and access to testing.

Paul Hunter, a professor in medicine at the Norwich School of Medicine, University of East Anglia, said to the Science Media Centre:

“Case control studies are often used to determine the effectiveness of vaccines after release of vaccines for general use. Effectiveness studies such as this show the ability of the vaccine to reduce disease in the real world use, but because of the non-randomised study design such studies may be prone to some degree of bias. Nevertheless effectiveness studies are an essential approach to showing whether the vaccine is indeed as good as the phase 3 trials suggest.”

The study population included all adults in England aged 70 years and older—over 7.5 million people. All COVID-19 testing in the community among eligible individuals who reported symptoms between 8 December 2020 and 19 February 2021 was included in the analysis.

The scientists compared medical records of groups of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals aged 70 or older who had been tested for COVID-19. The researchers quantified the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines by comparing the proportion of people in each group that tested positive for the disease. The effects of the COVID-19 vaccines on symptomatic disease were apparent 10 to 13 days after participants received the first doses. This is expected, as it often takes several days or weeks for vaccines to confer protection. The reduction in symptomatic COVID-19 infections improved up to 28 to 34 days after the first dose and plateaued at 70%.

The study observed that people aged 80 and older who received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine before 4 January 2021 had a higher chance of testing positive for COVID-19 in the nine days after vaccination compared to unvaccinated people during that period. This vaccinated group was 48% more likely to develop COVID-19 than unvaccinated people in the seven-to-nine day period after vaccination, once the data for the groups were adjusted for age, period, sex, region, ethnicity, care home, and social deprivation. These factors may influence the risk of COVID-19 and were used to adjust the figures to reduce bias in the observations caused by differences between the two groups.

The Gateway Pundit article stated that the report “actually showed a 48% rise in infections after the first dose of Pfizer and Astra Zeneca vaccines”. However, this is an incorrect interpretation of the results. There wasn’t an increase in COVID-19 infections following vaccination with the AstraZeneca vaccine, nor with the Pfizer vaccine after 4 January 2021, when the vaccine was administered to a wider population. The 48% figure only applied to a narrow window of seven to nine days after the first dose and the rate of infections fell after this time.

The Gateway Pundit article speculated that COVID-19 vaccines temporarily lower the immune response during the first two weeks, making vaccinated people more susceptible to COVID-19. However, as the authors of the study suggested, the most likely explanation for seeing this short-lived effect in only the first group of elderly people to be vaccinated was that these individuals were already at greater risk of COVID-19 infections at the time of vaccination:

“For example, those accessing hospital may have been offered vaccine early in hospital hubs [vaccination centers] but may also be at higher risk of COVID-19.”

The people vaccinated before 4 January 2021 were at least 80 years old and less likely to be in a care home than those vaccinated in the following weeks. After 4 January 2021, the vaccination program was expanded to include people in their seventies and a larger rollout in care homes. This later group of vaccinated individuals did not show an increased risk of COVID-19 infections compared to unvaccinated people in the first nine days, once the data were adjusted for known differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

The study also analyzed hospital admission data for people who received either COVID-19 vaccine. This showed that a single dose of either vaccine is approximately 80% effective at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations. The results also showed that individuals who tested positive for COVID-19 within 14 days of vaccination were at the same risk of hospitalization as unvaccinated individuals. This contradicts the suggestion in the Gateway Pundit article that the vaccine leads to more severe infections.

Beyond 14 days after vaccination, individuals who were vaccinated were 40% less likely to be hospitalized after testing positive for COVID-19 compared to unvaccinated people.

There wasn’t enough data to assess the effects of the AstraZeneca vaccine on COVID-19 deaths, but the study found that a single dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was 85% effective at preventing death from the disease.

In summary, the Public Health England report provides evidence that the Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines are effective after a single dose. The vaccines begin reducing symptomatic COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths after 10 to 14 days.

The unexpected observation of an increased risk of COVID-19 infections in the first nine days following vaccination was only seen in one group of people, who were 80 or older and the first to receive the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. This group was prioritized for vaccination because of their increased risk and may have been more likely to visit the hospital for other conditions. No increased risk of infection was seen when the vaccination program was expanded to a wider population.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Lopez Bernal et al. (2021) Early effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and ChAdOx1 adenovirus vector vaccine on symptomatic disease, hospitalisations and mortality in older adults in England. Preprint available on medRxiv.