- Health

Contrary to claim in Washington Times op-ed, COVID-19 shots meet the definition of a vaccine

Key takeaway

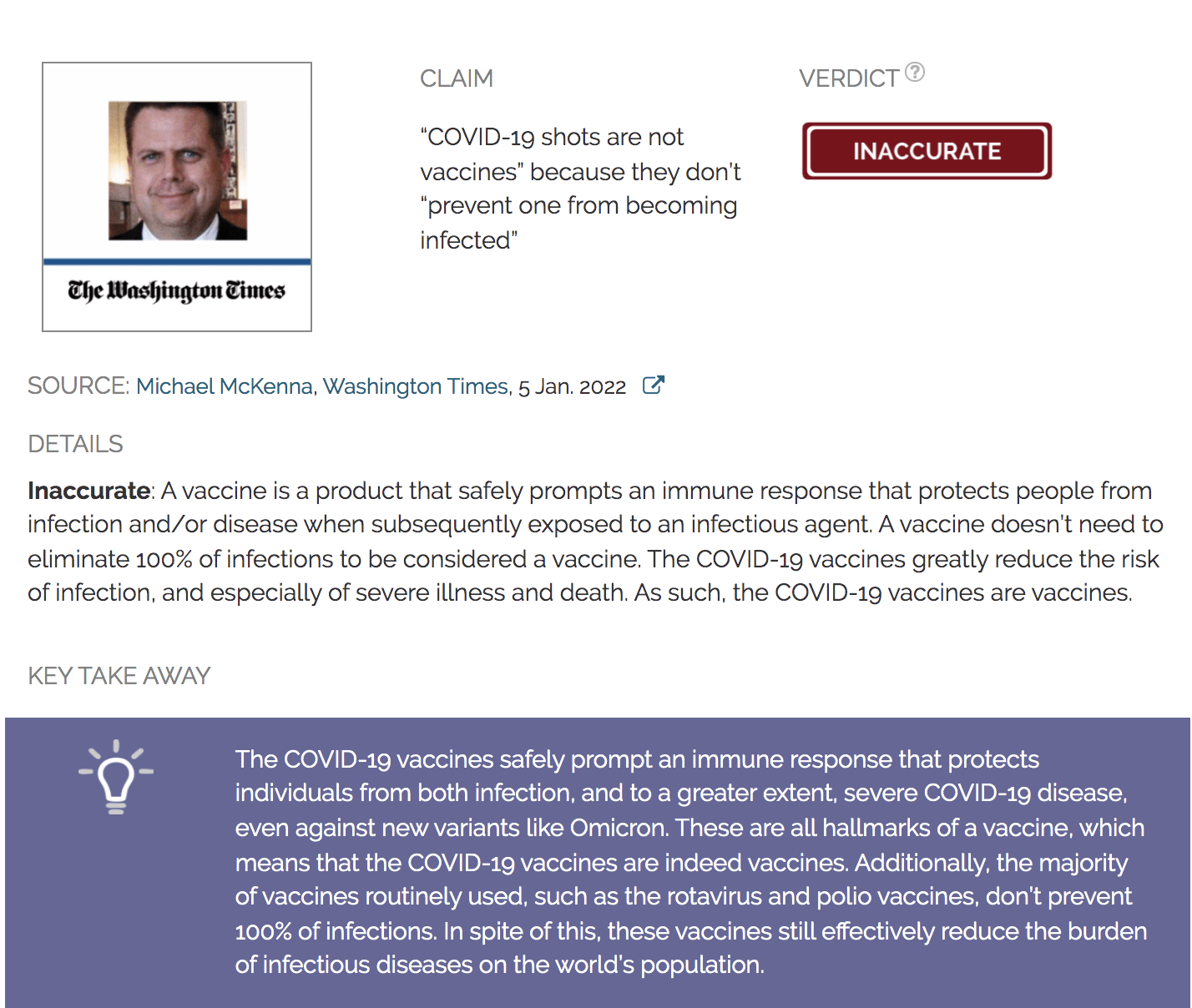

The COVID-19 vaccines safely prompt an immune response that protects individuals from both infection, and to a greater extent, severe COVID-19 disease, even against new variants like Omicron. These are all hallmarks of a vaccine, which means that the COVID-19 vaccines are indeed vaccines. Additionally, the majority of vaccines routinely used, such as the rotavirus and polio vaccines, don’t prevent 100% of infections. In spite of this, these vaccines still effectively reduce the burden of infectious diseases on the world’s population.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

Claim:

“COVID-19 shots are not vaccines” because they don’t “prevent one from becoming infected”

Verdict detail

Inaccurate: A vaccine is a product that safely prompts an immune response that protects people from infection and/or disease when subsequently exposed to an infectious agent. A vaccine doesn’t need to eliminate 100% of infections to be considered a vaccine. The COVID-19 vaccines greatly reduce the risk of infection, and especially of severe illness and death. As such, the COVID-19 vaccines are vaccines.

Full Claim

“A ‘vaccine’ is commonly understood to be a product that stimulates a person’s immune system to produce immunity to a specific disease. Vaccines prevent one from becoming infected with a disease and prevent the transmission of the disease to others”; “whatever shots we took earlier in the year were not vaccines”.

Review

In an op-ed from 5 January 2022, Michael McKenna, a columnist for The Washington Times, a daily newspaper published in Washington D.C., claimed that the “COVID-19 shots are not vaccines,” but a “preventative therapeutic” that had no impact on infection or transmission.

This is not the first time this type of claim has been made. In September 2021, Alex Berenson, a writer dubbed the “Pandemic’s Wrongest Man” for his consistently wrong forecasting of the pandemic by The Atlantic, made the same claim, saying the COVID-19 vaccines were more like a therapeutic. In October 2021, social media users used a falsified court record claiming an Australian professor said that the COVID-19 vaccines were not vaccines, when the professor didn’t make this claim.

The crux of the argument made by individuals who claim the “COVID-19 shots are not vaccines” is that they don’t prevent infection or transmission. However, a vaccine doesn’t have to prevent 100% of infections to make a difference in reducing the burden of an infectious disease. In fact, as we’ll show below, most vaccines don’t prevent infection and transmission.

The COVID-19 shots are vaccines

To start off, let’s look at how vaccine experts define vaccines. In their guide to vaccinology published in Nature Reviews Immunology, Andrew Pollard, the director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, and Else Bijker, a pediatrician and researcher also at the Oxford Vaccine Group, define vaccines as “a biological product that can be used to safely induce an immune response that confers protection against infection and/or disease on subsequent exposure to a pathogen”[1]. Pollard and Bijker further define protection as “the state in which an individual does not develop disease after being exposed to a pathogen”.

Now, we’ll look at COVID-19 vaccines and how they work. When a person receives a COVID-19 vaccine, they’re given inactivated SARS-CoV-2, part of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, or instructions on how to produce a protein from SARS-CoV-2. Regardless of the type of vaccine, all the COVID-19 vaccines train the immune system to identify and respond to future exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines build this immunity in a safer manner than catching COVID-19.

And how does this immune response fare when exposed to SARS-CoV-2? Due to both declining levels of antibodies and COVID-19 variants such as Omicron, which studies suggest can evade both infection- and vaccine-induced immunity, breakthrough infections are happening more frequently. However, breakthrough infections aren’t equivalent to infections in unvaccinated individuals.

Vaccinated individuals are about five times less likely to be infected compared to unvaccinated people, according to a study by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that monitored COVID-19 cases between April and July 2021[2]. Additionally, while breakthrough infections can cause mild to moderate COVID-19 illness, the vaccines are very effective at keeping these infections from progressing to serious illness, hospitalization, or death. The same CDC study found that the risk of both hospitalization and death in vaccinated individuals was reduced over 10 times compared to unvaccinated individuals[2].

This protection remains even in scenarios in which the Omicron COVID-19 variant, a variant of concern that was first reported in late November 2021, is prevalent. In New York State, for instance, even as the number of breakthrough infections quintupled in December 2021 and breakthrough hospitalizations doubled, unvaccinated individuals were still at a higher risk of both infection (six times) and hospitalization (14 times) than vaccinated people. In his op-ed, McKenna acknowledged that the COVID-19 vaccines do protect against death and hospitalization, but not that they also decrease the risk of infection.

In short, the COVID-19 vaccines fit Pollard and Bjiker’s definition of vaccines: they’re a biological product, they’re safe, they induce an immune response, and they confer protection against infection, but especially against serious disease, hospitalization and death.

Majority of routine vaccines don’t prevent 100% of infections

In the op-ed, McKenna claimed that the COVID-19 vaccines don’t fit the term vaccine as it is “understood by native English speakers everywhere,” with McKenna defining vaccines as products that “prevent one from becoming infected with a disease and prevent the transmission of the disease to others”. Though McKenna treated them as processes that are independent of each other, transmission and infection of infectious agents like viruses are intrinsically interdependent; a person cannot transmit a virus unless they’re infected with and actively replicating that virus. As such, for a vaccine to prevent transmission, it would also have to prevent infection.

Immunity that prevents a person from being infected is known as sterilizing immunity. However, as Sarah Caddy, a clinical research fellow in viral immunology at the University of Cambridge, explained in an article in The Conversation, “most vaccines that are in routine use today do not achieve this” and it’s “actually extremely difficult to produce vaccines that stop virus infection altogether”.

Caddy provided two examples in her article: the rotavirus vaccine, which only prevents severe disease, and the polio vaccines. Despite not preventing 100% of infections, Caddy pointed out that both vaccines have been extremely important, with the rotavirus vaccine leading to almost 90% fewer hospital visits due to rotavirus, and polio being close to global eradication.

In summary, the COVID-19 vaccines are vaccines because they safely induce an immune response that offers protection against both infection, and particularly, against severe COVID-19 disease when a person is subsequently exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, most vaccines don’t prevent 100% of infections and, as such, don’t eliminate transmission. Despite this, vaccines have played and continue to play an important role in decreasing the burden of many infectious diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Pollard & Bijker. (2021) A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nature Reviews Immunology.

- 2 – Scobie et al. (2021) Monitoring incidence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, by vaccination status – 13 U.S. jurisdictions, April 4 – July 17, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.