- Health

A person’s decision not to vaccinate affects others, as unvaccinated people are more likely to get infected and spread COVID-19

Key takeaway

Herd immunity occurs when a certain proportion of the population has acquired immunity to a virus, either through vaccination or previous infection. In this way, the immune individuals help protect those who aren’t immune. Herd immunity is important for many people in the community who are forced to rely on others for indirect protection from an infectious disease. Some examples are children below the age of 12, who currently aren’t eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S., and those with a weakened immune system, like cancer patients and people who received organ transplants.

Reviewed content

Verdict:

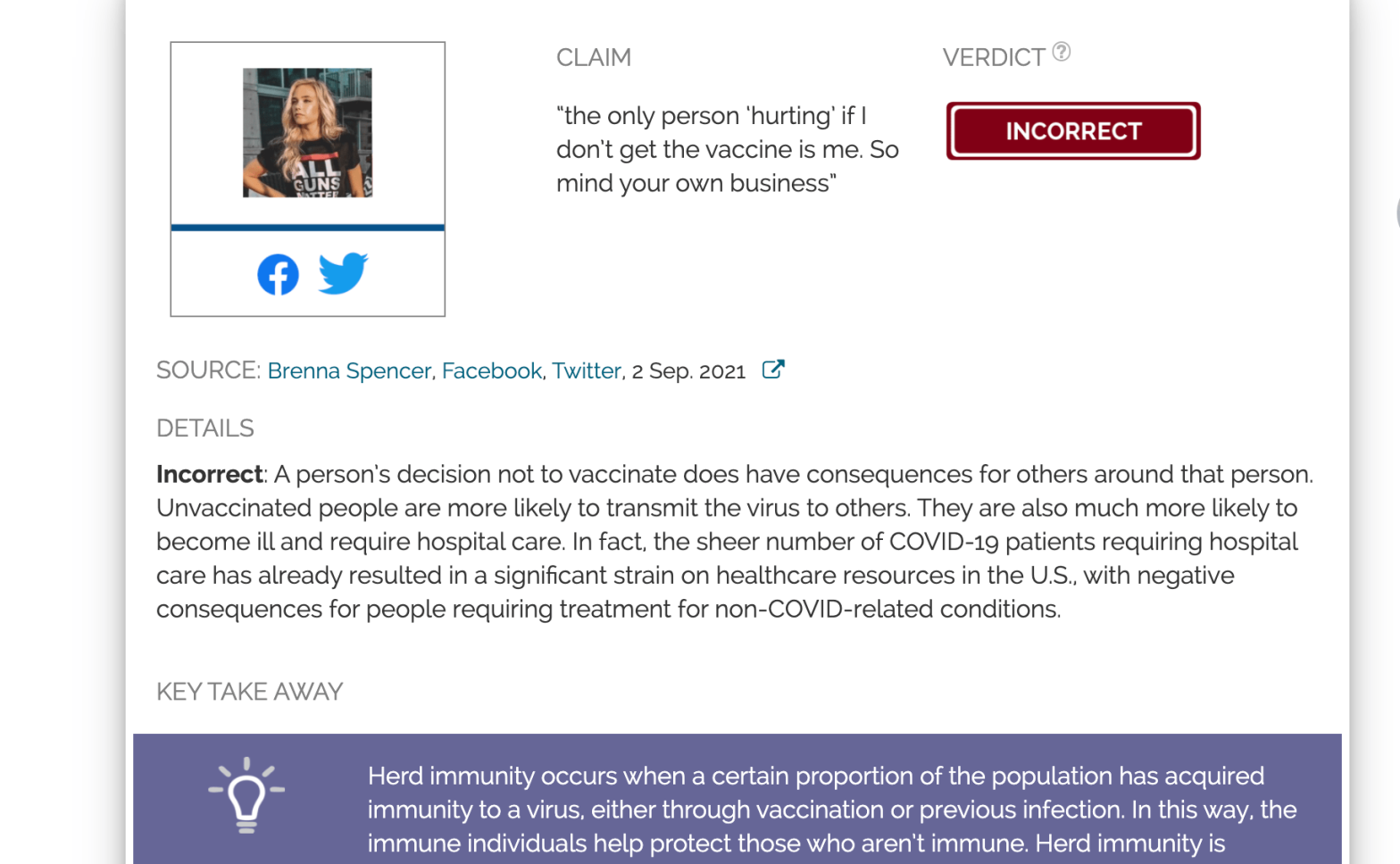

Claim:

“the only person ‘hurting’ if I don’t get the vaccine is me. So mind your own business”

Verdict detail

Incorrect: A person’s decision not to vaccinate does have consequences for others around that person. Unvaccinated people are more likely to transmit the virus to others. They are also much more likely to become ill and require hospital care. In fact, the sheer number of COVID-19 patients requiring hospital care has already resulted in a significant strain on healthcare resources in the U.S., with negative consequences for people requiring treatment for non-COVID-related conditions.

Full Claim

“If you got the vaccine, you don’t need me to. If you got the vaccine, you can still get COVID, & you can still spread COVID. But you won’t be ‘as sick.’ So, the only person ‘hurting’ if I don’t get the vaccine is me. So mind your own business.”

Review

A Facebook post claiming that “the only person ‘hurting’ if I don’t get the vaccine is me” received more than 7,700 engagements on the platform. The author of the post is Brenna Spencer, a political activist who previously worked as a legal assistant. Spencer, who has more than 76,000 followers on Twitter, also posted a tweet with a similar message on 2 September 2021, claiming that the only people vaccinated people protect are themselves.

Spencer’s post contains common themes of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation, some of which were previously debunked by Health Feedback, as we will explain below.

The claim that the decision not to vaccinate only affects the person making that decision is false. Many countries aim to vaccinate as many people as possible in order to achieve a level of community protection (herd immunity). Herd immunity occurs when a certain proportion of the population has acquired immunity to a virus, either through vaccination or previous infection. When this happens, the immune individuals help protect those who aren’t immune.

This is important, because there are many people in the community who are forced to rely on others for indirect protection through herd immunity. One notable example is children below the age of 12, who currently aren’t eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.. While children don’t become ill or hospitalized as often as adults, a certain proportion of them do become seriously ill, and some have also died. Furthermore, with the spread of the Delta variant, researchers observed children being hospitalized at a higher rate. A report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found a ten-fold increase in hospitalization rates for children aged four and below[1].

Others in the community that also rely on indirect protection are those with a weakened immune system. Among this group are cancer patients and people who received organ transplants. While they can get vaccinated, they don’t receive the full benefits of the vaccine that a healthy person who isn’t immunocompromised would.

In short, herd immunity works—this is exemplified by the success of vaccination campaigns that eradicated once-common childhood diseases, like measles and polio.

Some have questioned the utility of the COVID-19 vaccines since they aren’t 100% effective at preventing transmission and infection. It’s important to keep in mind that no vaccine is 100% effective, not even the measles and polio vaccines. These vaccines serve as reminders that it isn’t necessary for vaccines to be 100% effective to have a significant benefit for public health. Indeed, in an article for The Conversation, immunologist Sarah Caddy discussed why it isn’t necessary for a vaccine to block transmission fully to reduce the number of infections. Health Feedback also addressed the same argument here and here.

Apart from reducing the likelihood of infecting vulnerable individuals in the community, the COVID-19 vaccines also help keep individuals out of the hospital. Reports from Israel and the U.K. suggest that COVID-19 vaccines retain a high level of effectiveness against severe illness and hospitalization, even in the face of the Delta variant. Data from Israel’s health ministry indicated that two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine are 88% effective against hospitalization and 91% effective against severe illness. Similarly in the U.K., an analysis by Public Health England indicated that two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine provide 96% effectiveness against hospitalisation, while two doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine are 92% effective against hospitalisation.

This isn’t a trivial contribution. The sheer number of COVID-19 patients requiring hospital care is placing a strain on the healthcare system in various parts of the U.S. This strain even proved fatal in the case of U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson, who died from a treatable condition unrelated to COVID-19 because there were no intensive care unit beds in the hospital for him. In the U.S., unvaccinated people make up the majority of COVID-19 hospitalizations. Data from 40 states show that fully vaccinated people make up less than 5% of hospitalizations.

Overall, the data we have shows that the strain on healthcare systems—and the negative outcomes associated with it—could have been avoided had more people decided to vaccinate.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Delahoy et al. (2021) Hospitalizations Associated with COVID-19 Among Children and Adolescents — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1, 2020–August 14, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.