- Climate

Insight into the scientific credibility of The Guardian climate coverage

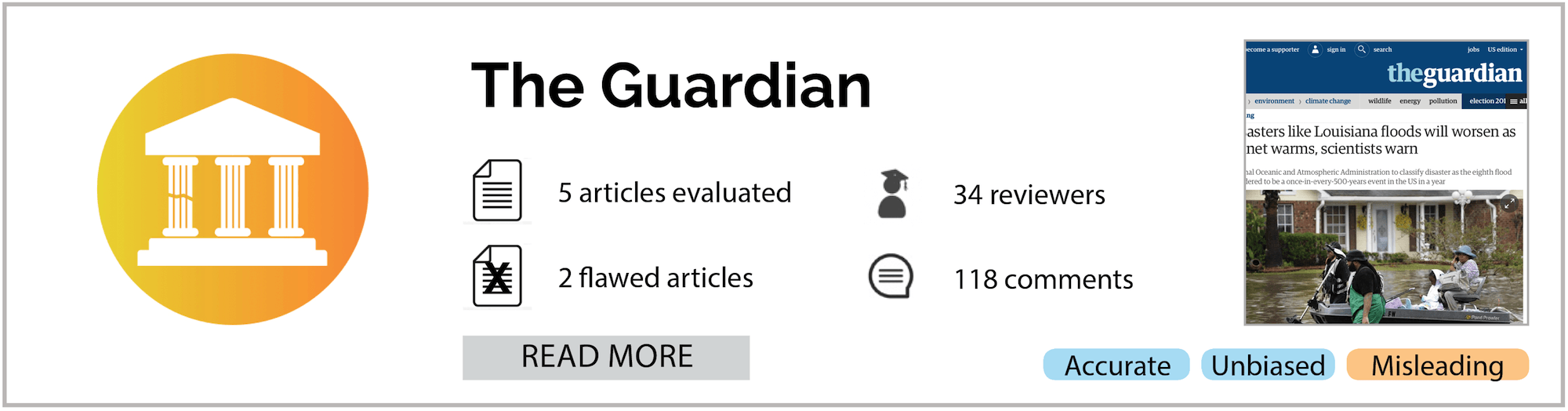

Over the past two months, Climate Feedback has asked its network of scientists to review 5 widely read articles published by The Guardian. Three were found to be both accurate and insightful. Two were found to contain inaccuracies, false or misleading information, and statements unsupported by current scientific knowledge.

Insightful climate reporting in The Guardian

Climate Feedback’s analysis of The Guardian article written by Damian Carrington and published on September 23, “Greenland’s huge annual ice loss is even worse than thought,” was found to be accurate by all the reviewers. For instance, Dr. Lauren Simkins qualified it as “a succinct and accurate assessment of past and present ice mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet that is supplemented by insightful comments from scientific experts.” Another analysis, of The Guardian’s “Disasters like Louisiana floods will worsen as planet warms, scientists warn,” written by Oliver Milman and published on August 16, rated that article as having “high” scientific credibility, with Dr. Ben Henley noting that

“The article is accurate. The issue of increasing precipitation extremes due to climate change is presented well. Heavy precipitation increases have been observed, and are projected to worsen with climate change.”

Guests’ misleading claims go unchallenged

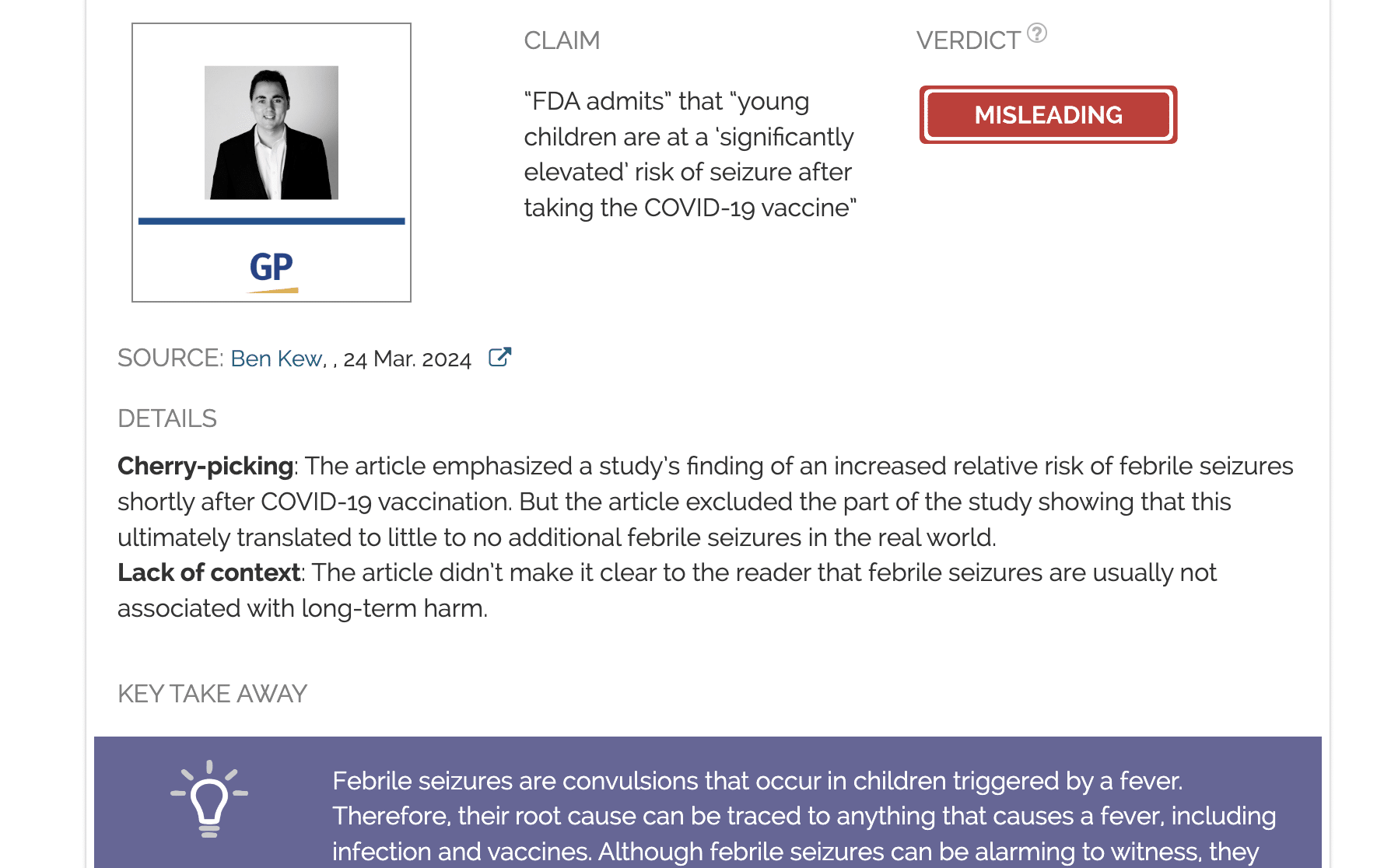

By contrast, two articles published in The Guardian’s Saturday interview section and The Observer ranked “low” on Climate Feedback’s “scientific credibility” scale. On August 21, The Guardian/The Observer featured an article that bore the sensationalistic headline “Next year or the year after, the arctic will be free of ice.” The article, an interview with scientist Peter Wadhams that also serves to promote his latest book, mixes scientific claims with the author’s speculation. As scientists explain in Climate Feedback’s analysis of the article, Prof. Wadhams’ core claim is unsupported by current scientific understanding: scientists’ best projection is for an ice-free arctic in a few decades and the inherent uncertainty in the climate system makes it impossible to pin the exact year this will happen. Some scientists also noted that it would have been easy for the journalist to find out that Prof. Wadhams’ has a track record of making projections that do not occur. In his contribution to the analysis, Dr. Patrick Grenier noted:

“The journalist has chosen to interview a researcher known for having made wrong predictions in the past, and he has chosen not to balance Wadham’s view against that of other sea ice experts. Wadhams’ alarmism is potentially harmful, because when such spectacular predictions are not realized some people may perceive the whole scientific community or science itself as untrustworthy.”

On September 30, The Guardian published another interview, this time with former scientist James Lovelock, who was also promoting an upcoming book launch. In the article Lovelock makes a number of claims about climate change that are at odds with current scientific understanding or simply untrue. For instance, he argues that “CO2 is going up, but nowhere near as fast as they thought it would. The computer models just weren’t reliable.” In Climate Feedback’s analysis, Professor Ken Caldeira notes:

“This statement is just plain wrong. Atmospheric CO2 content has recently surpassed 400 ppm and this rate of increase is in line with model projections.”

Verifying extraordinary claims

The publication of interviews that mix opinion and science, while failing to differentiate between the two, undermines the credibility of otherwise accurate reporting of climate issues in The Guardian. It also confuses the public on the issue and undermines the credibility of the scientific community. This type of coverage finds an eager audience in climate change contrarians who use it to paint the entire climate science community as unreliable. While the interview format is inherently just one person’s perspective, we argue it would be preferable for the journalist to fact-check and challenge extraordinary statements. As climate scientist Zeke Hausfather points out in his analysis of the Lovelock interview:

“While the article presumably faithfully reports Lovelock’s opinions, when those opinions are couched as scientific statements more pushback (or at least nuance) might be warranted.”

Doing so would bring coverage more in agreement with The Guardian’s guideline stating that “The Press must take care not to publish inaccurate, misleading or distorted information,” thereby enhancing The Guardian’s credibility and better informing its readers.