- Health

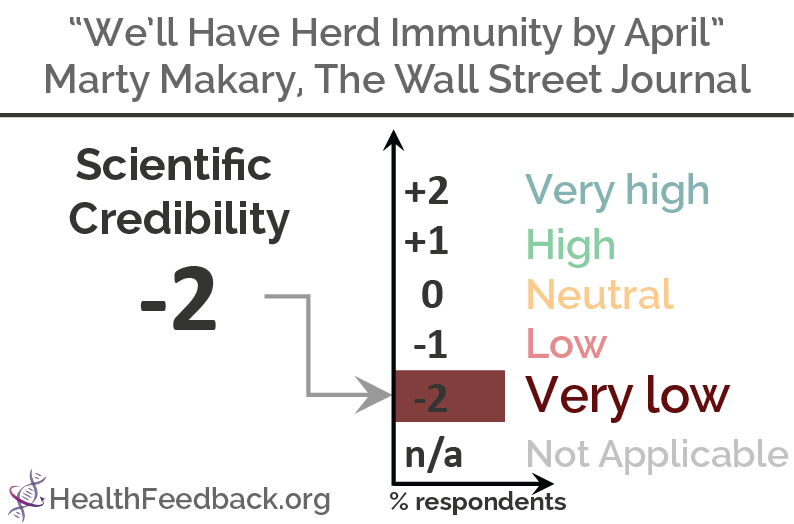

Misleading Wall Street Journal opinion piece makes the unsubstantiated claim that the U.S. will have herd immunity by April 2021

Reviewed content

Headline: "We'll Have Herd Immunity by April"

Published in The Wall Street Journal, by Marty Makary, on 2021-02-18.

Review

SUMMARY

This Wall Street Journal opinion piece, published on 18 February 2021, claimed in its headline that the U.S. will “have herd immunity by April”. Written by Marty Makary, a professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the article received more than 220,000 interactions and 37,000 shares on Facebook, according to the social media analytics tool CrowdTangle. Its claim was also propagated through social media posts by other outlets, such as this video by former U.S. Representative Ron Paul and this article by Zero Hedge, labeled a “conspiracy-pseudoscience” source by Media Bias/Fact Check.

Herd immunity is a state in which a certain proportion of individuals in a population are immune to an infectious disease. As explained in this article by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health:

“For example, if 80% of a population is immune to a virus, four out of every five people who encounter someone with the disease won’t get sick (and won’t spread the disease any further). In this way, the spread of infectious diseases is kept under control. Depending how contagious an infection is, usually 50% to 90% of a population needs immunity to achieve herd immunity.”

The headline’s claim is built in large part on the assumption that “55% of Americans have natural immunity” to COVID-19 through prior infection. However, experts who reviewed the article told Health Feedback that this assumption wasn’t supported by the data. [See our reviewers’ overall feedback.]

Marm Kilpatrick, a professor at the University of California Santa Cruz who studies disease ecology, found that the article’s figures for the number of COVID-19 infections detected by testing, as well as the infection fatality rate—which measures the proportion of infected people who die from the disease—were unsubstantiated.

Kilpatrick explained that the proportion of COVID-19 infections detected by testing is unknown, since there are no representative serosurveys available for the U.S. Serosurveys, or seroprevalence studies, measure the proportion of people who have antibodies to a pathogen. These studies inform researchers about the extent of a pathogen’s spread in a population.

“The author uses a value of 15.4 percent (1/6.5), which produces a very different answer than if the author had used his other proposed value of 25 percent (1/4),” Kirkpatrick pointed out. “Instead of the 55 percent seroprevalence claimed, seroprevalence would be 34 percent. The fraction of infections detected by testing may even be higher than 25 percent, which would produce an even lower estimate of seroprevalence.”

The article also extrapolated the total number of COVID-19 infections by relying on the infection fatality rate and the total number of deaths. However, the article underestimated the infection fatality rate. Given a fixed number of deaths, the higher the infection fatality rate, the smaller the size of the infected population.

“The best available data for the U.S. population indicates a value of 0.6,” Kilpatrick said, citing a study by O’Driscoll et al.[1]. “Using the same number of deaths as the author”, which is 0.15 percent of the U.S. population, this would translate to 25 percent of the U.S. population having been infected, “rather than two-thirds as the author claimed.”

In short, the article’s statement that “55 – 66 percent of the U.S. population has already been infected and has immunity is not supported by available data,” he concluded.

Apart from the miscalculations in the total number of infections, the article also made several inaccurate assertions about COVID-19 reinfections and immunity.

Tara Smith, an epidemiologist and professor at Kent State University, refuted the article’s claim that “when [reinfections] do occur, the cases are mild”, citing a case report documenting COVID-19 cases around the world that were more serious upon reinfection[2].

Virologist Angela Rasmussen pointed out that the article misrepresented a study by Sekine et al. on T cells[3]: “T cell immunity is presented [in the Wall Street Journal opinion piece] as being an indicator of protective immunity […] this is an incorrect interpretation of the data cited about T cells to support that assertion”.

Eric Topol, a cardiologist and professor of molecular medicine at the Scripps Research Institute, highlighted several problems with the opinion piece in a Twitter thread:

William Hanage, an associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard University, pointed out that the article’s use of the Brazilian city of Manaus as a real-life example of successful protection through natural infection is inaccurate and misleading.

“The article fails to mention that since the research it cites was published, Manaus has suffered a surge of infections even worse than the one that it saw at the start of the pandemic[4],” he said.

As reported in a study by Buss et al.[5], even though an estimated 76 percent of Manaus’ population was infected, the spread of COVID-19 wasn’t halted. In fact, news reports indicated that a second wave of infections overwhelmed hospitals in early 2021. Buss et al. warned that “Manaus represents a ‘sentinel’ population, giving us a data-based indication of what may happen if SARS-CoV-2 is allowed to spread largely unmitigated.”

Curiously, the Lancet commentary cited in the opinion piece to support the claim actually reported COVID-19 resurgence in Manaus despite the high level of infection in its population[4]. This contradicts the Wall Street Journal article’s suggestion that Manaus had achieved protection through natural infection.

One reason for the resurgence may be the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants[4,6], although other factors, such as waning population immunity, may also be a contributing factor.

“It is not known to what extent the circulating variant P.1 contributed to the surge, or how many cases were reinfections, but it should be more than enough to demonstrate the dangers of trusting to ‘herd immunity’ from infection for protection,” Hanage said.

Cases in the U.S. have indeed been falling in recent weeks. The reason for this is still unclear, but this Washington Post article explored several possible explanations. Apart from vaccinations, other potential contributing factors that scientists highlighted were changes in people’s behavior, such as greater adherence to physical distancing and the use of face masks, as well as fewer COVID-19 tests being performed due to a shift in focus from testing to vaccinating. However, an analysis of the number of cases and positivity rate in this Health Feedback review indicated that the decrease is genuine and not simply due to fewer tests being performed.

In summary, the Wall Street Journal opinion piece’s claim that the U.S. will achieve herd immunity by April 2021 is unsupported by the available data. Its claim that natural infection confers sufficient herd immunity to end the COVID-19 epidemic in the U.S. also doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, when we consider the example of Manaus. The city experienced a largely uncontrolled spread of COVID-19, which resulted in a high infection rate. Yet the city still saw a resurgence of COVID-19 that was worse than the first wave.

While the U.S. is indeed experiencing a fall in the number of new COVID-19 cases, scientists have urged Americans to avoid complacency given the threat posed by the new virus variants.

Former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tom Frieden told CNN:

“We’ve had three surges. Whether or not we have a fourth surge is up to us, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.”

You can read the original Wall Street Journal article here.

Scientists’ Overall Feedback

Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz

The article’s claim that the U.S. is near herd immunity rests on two numbers: 1) the detection of infections by testing (claimed to be 10 – 25 percent) and 2) the infection fatality rate (claimed to be 0.23 percent).

- 1) The fraction of infections detected by testing is unknown, as there are no representative serosurveys for the U.S. on which to quantify this number. The author uses a value of 15.4 percent (1/6.5), which produces a very different answer than if the author had used his other proposed value of 25 percent (1/4). Instead of the 55 percent seroprevalence claimed, seroprevalence would be 34 percent. The fraction of infections detected by testing may even be higher than 25 percent, which would produce an even lower estimate of seroprevalence.

- 2) The infection fatality rate is an age-specific value that also depends on gender and pre-existing morbidities. The best available data for the U.S. population indicates a value of 0.6 (95% CI: 0.51-0.7), which comes from Figure 2 of this study by O’Driscoll et al.[1].

Using the same number of deaths as the author indicates that 0.15%/0.6% = 25% of the U.S. population has been infected, rather than two-thirds as the author claims.

Thus, the author’s argument that 55 – 66 percent of the U.S. population has already been infected and has immunity is not supported by available data.

Professor, College of Public Health, Kent State University

There are a lot of errors here, probably because the author has no background in infectious disease. The author of the T cell research cited says it’s misused (see that and more info in this Twitter thread). And not all reinfections are mild[2].

Associate Professor of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health

This is not an exhaustive list.

The estimates of how many have been infected do not tally with those of others (for example, see this analysis of attack rate). But because these numbers inevitably lag, the best way to show this is probably the section where the national per capita mortality is used to estimate how many people have been infected. In reality, this statistic varied hugely by state, with more than 2500/million dead in New Jersey, less than 1000/million in Virginia, and about 300/million in Hawaii. This suggests great regional differences in the amount of infection that has occurred and the resulting immunity. Note that the role of the holidays in producing a peak is illustrated by the fact that Hawaii saw a small peak around the same time as the rest of the country in early January, despite having little evidence of immunity and a very different climate. While cases are down nationally, in some regions—including some with very high per capita mortality rates—they are showing signs of plateauing.

There are numerous misstatements about the weight of evidence when it comes to reinfections. It should be noted that if your bar for reinfections is two PCR tests with a genome from each, that makes them very hard to detect—even more so when, as the article states, many initial infections are never detected! Probably the best single counterpoint is the example of Manaus, which is held up in the article as an example of herd immunity. The article fails to mention that since the research it cites was published, Manaus has suffered a surge of infections even worse than the one that it saw at the start of the pandemic[4,5]. It is not known to what extent the circulating variant P.1 contributed to the surge, or how many cases were reinfections, but it should be more than enough to demonstrate the dangers of trusting to “herd immunity” from infection for protection.

The article’s statement that “most infections are asymptomatic” is not true[7].

Finally, the arrival of the B.1.1.7 variant which is approximately 50% more transmissible means that a larger proportion of the population needs to be immune to drop the reproductive number below one[8]. While April may well be considerably better than the worst of the winter, this should be placed in the context of seasonality[9]. Overemphasizing population immunity is misleading and could discourage people from vaccination.

REFERENCES

- 1 – O’Driscoll et al. (2020) Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature.

- 2 – Selvaraj et al. (2020) Severe, Symptomatic Reinfection in a Patient with COVID-19. Rhode Island Medical Journal.

- 3 – Sekine et al. (2020) Robust T Cell Immunity in Convalescent Individuals with Asymptomatic or Mild COVID-19. Cell.

- 4 – Sabino et al. (2021) Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. The Lancet.

- 5 – Buss et al. (2021). Three-quarters attack rate of SARS-CoV-2 in the Brazilian Amazon during a largely unmitigated epidemic. Science.

- 6 – Faria et al. (2021) Genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus: preliminary findings. Virological.

- 7 – Meyerowitz et al. (2021) Towards an accurate and systematic characterisation of persistently asymptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

- 8 – Anderson and May. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control.

- 9 – Rucinski et al. (2020) Seasonality of Coronavirus 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43: From 2014 to 2020. Mayo Clinic Proceedings.